Alumni in the Concert Hall: Performers and Composers

The most famous Black classical musicians of the early twentieth century were all performers and composers: Harry T. Burleigh, Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, Roland Hayes, William Grant Still, William Dawson, Florence Price, Margaret Bonds. The majority of Black classical musicians, however, worked as teachers, and the Washington Conservatory was representative among higher education institutions in producing far more music teachers than performers or composers. Still, at least several concert musicians and composers graduated from the institution between 1910 and 1914, and while they never achieved the fame of the figures cited above, there is no question that they contributed to American musical life in the early twentieth century both in DC and nationally.

Washington, DC Area Performances by Washington Conservatory Graduates Color-Coded by Venue Type

This map demonstrates church performances (shown in red) were widely spread throughout the DC area, while theater performances (shown in green) were concentrated in the U street corridor and downtown Washington, DC.

The thirty Washington Conservatory graduates we’ve studied performed mostly in community settings, at schools, churches, theaters, and homes. While segregation certainly limited the scope of the performances from these graduates, the black-owned venues they frequented—like the Howard Theatre—began to flourish in the 1910s, gaining better reputations and being viewed as symbols of Black pride by some—but not all—African Americans (read more about the theater here).1 According to musicologist Douglas Shadle, racial discrimination likely limited class mobility for all but the most esteemed performers.2 A standard musical career path for middle-class Black women often consisted of matriculating at a normal school, learning just enough to teach the next generation, and becoming a teacher; technical study and public performance opportunities were rare.3 Yet even where career options were confined—as Dr. Phylicia Bowman and Dr. Tammy Kernodle both acknowledged—African American women in particular managed to preserve cultural practices, ensuring that traditions (musical and non-musical) were sustained, especially in schools, churches, and community centers.4

Roughly 63% of the performances by 1910-1914 Washington Conservatory graduates that we located in newspapers occurred within DC, including many performances at the conservatory itself. Out of the known pieces performed at the conservatory in the 1910s, approximately 28% of known composers were Black, while 72% were white—a much higher proportion than in the population at large.5 In the same decade, 95% of known pieces performed (where the composer’s gender was known) were by male composers, while pieces by female composers were performed only 5% of the time.6 The four most frequently performed composers during Harriet Gibbs Marshall’s tenure at the conservatory (1903-41) were Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Harry T. Burleigh, Frederick Chopin, and Ludwig Van Beethoven.7

Experience a Spotify playlist sampling some repertoire performed at the conservatory’s commencement and other recitals here.

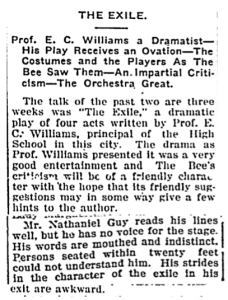

After graduating, Washington Conservatory alumni participated actively in DC musical life. Consider “The Exile,” a theater production performed in DC in June 1915 that was written for 1910 alum Nathaniel Guy, in which Washington Conservatory dance faculty member Edna Gray and alumna Jewel Jennifer performed.8

In April 1926, Henry L. Grant provided the music for a pageant at Armstrong Technical High School, conducting the “Dunbar High School Chorus and Orchestra and the Cleveland Chorus and Folk Singers.”9 Another exciting performance was at a packed concert with 3,000 attendees at Richmond, Virginia’s First Baptist Church. Wilhelmina B. Patterson performed, singing “Johnson’s ‘The Awakening,” along with Hampton Institute Singers and two Black colleagues at the institution, who included renowned composer-pianist R. Nathaniel Dett “who played his own composition, ‘Incarnation.’”10 Click here for a non-exhaustive list of nearly 250 performances by Washington Conservatory alumni we uncovered as part of our research.

Performances by Washington Conservatory Graduates on the National Level

Categorized by location type, this map shows the spread of Washington Conservatory graduate performances around the United States. Based on documented performances in newspapers, the thirty alumni performed in 12 states besides Washington, DC (most performances did occur in DC). The Northeast comprised most of the music-making, with Virginia, Connecticut, and New York having the next most performances. Graduates also performed in Midwestern cities with large African American populations, like Chicago and East St. Louis, Illinois, in addition to a few times in Southern states including Kansas and Texas.

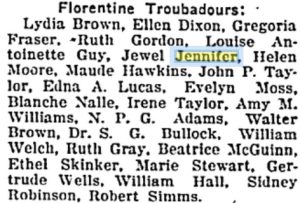

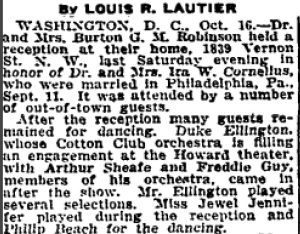

While performances at theaters, churches and schools comprise the most common performance venues both nationally and in Washington, DC, more alumni performed at radio stations outside of the city proper than within it. Jewel J. Phillips, Daisy O. Westbrook, and Wilhelmina B. Patterson all performed on the radio at some point, with Phillips entertaining over the airwaves most frequently. Phillips—who appeared on WMAL radio in DC, WJSV radio in Virginia, and WEVD radio in New York City in multiple capacities and may have also performed on Broadway—accompanied Nathaniel L. Guy’s son Barrington Guy on several radio gigs.11 Notably, as listed in the national edition of the Chicago Defender on October 10, 1931, she opened for Duke Ellington when he “played several selections” at a wedding reception in Washington, DC.12

Another graduate who overlapped at a performance with a famous musician of the era was J. Cleveland Lemons. In 1921 in Columbus, Ohio, Lemons played the pipe organ for a gig with Clarence Cameron White, “the distinguished violinist, composer” who was also a violin instructor and administrator at the Washington Conservatory in its first few academic years.13 He also participated in a “festival of music and art” at Central State University in Xenia, Ohio, in 1946, where the Fisk Jubilee Singers performed as well.14

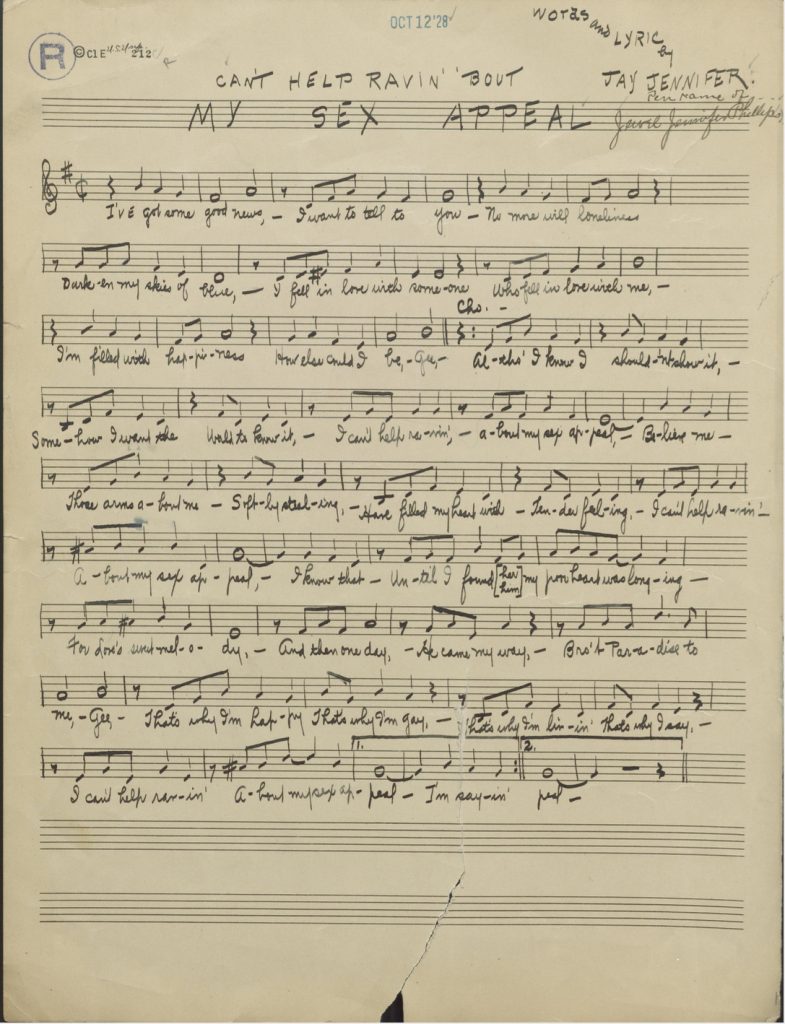

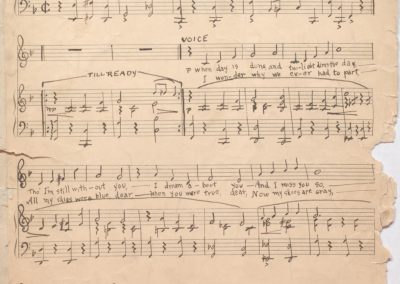

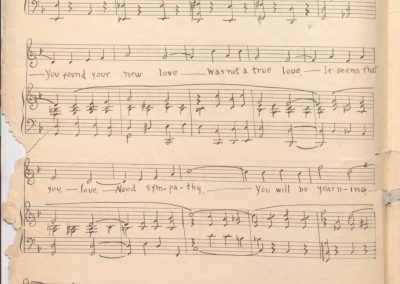

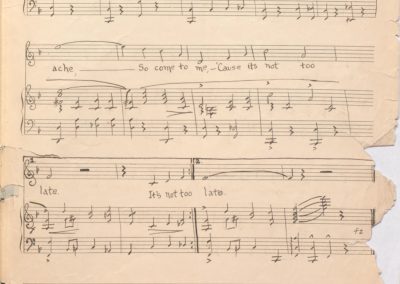

Click the image to enlarge. Jay Jennifer, “Can’t Help Ravin’ ‘Bout My Sex Appeal” (Washington, DC: Jewel Jennifer Phillips, 1928), accessed July 18 2022, Library of Congress Performing Arts Reading Room.

Out of the 30 Washington Conservatory graduates we researched, only two—Arthur R. Grant and Jewel J. Phillips—are known to have gone on to have composed and published their compositions. For example, Arthur R. Grant wrote several songs for musicals, and at least three tunes for the Broadway show “The Logic of Larry” in 1919, including “Pals First (Will be Pals to the Last” (orchestra parts for which are still available) and “Dear Mother of Mine,” both of which are available as sheet music.15 The songs are all in typical Tin Pan Alley verse-chorus form and treat topics such as friendship, motherly devotion, and romantic relationships. One song, “Dum-Deedle-Dee-Um Dumb Dora,” mocks the inelegant comportment and dialect of a romantic interest in a way that suggests the legacy of blackface minstrelsy.16 Grant produced a number of additional known compositions ranging from 1917-24.17One of them—”Drifting along (Why don’t you drift home)”—was recorded in 1926 and is available here.18

We are grateful to Cait Miller, research librarian at the Library of Congress, for sharing two unpublished pieces by Jewel Jennifer Phillips.19 Phillips pursued a career on Broadway as a performer and, apparently, a songwriter. One manuscript, “It’s Not Too Late,” is written for piano and voice and dated 1928.20 With dense rhymes reminiscent of Cole Porter and extended harmonies that point to jazz and the blues more than traditional Tin Pan Alley, “It’s Not Too Late” is an invitation to a lover who has left the singer for another: “It’s not too late, dear/To come to me/Don’t hesitate dear/It had to be/You found your new love/Was not a true love/It seems that you love/Need sympathy.”21 Another unpublished manuscript, titled “Can’t Help Ravin’ ‘Bout My Sex Appeal,” includes the attribution “Words and Lyric by Jay Jennifer,” an obvious pseudonym for Jewel Jennifer Phillips.22 (The composer may have adopted a masculine-sounding pen name to circumvent sexism in the sheet music industry). Written as a vocal score without accompaniment, the harmonic progression in the chorus is easily extrapolated from the melody as Amin7, D6, Gmajor7, Eminor9, Amin7, D, G6, although the bridge harmony remains somewhat enigmatic.23

Please enjoy our recreation of the sound world created by Jennifer’s and Arthur’s works with the following homemade Musical Geography Project recordings. The first clip is Jennifer’s “It’s Not Too Late;” the second is Grant’s “Bobbsy.” You can follow along in the score by clicking one image belong the recordings, then using the arrows to navigate through the next pages.

Though these pieces are delightful and clearly the work of talented composers, it’s important to remember that both Grant and Jennifer were also performers and teachers at various points throughout their lives. While most Washington Conservatory graduates were music teachers for whom we found few performances outside of their immediate communities, Jennifer and Grant’s range—both geographically and in terms of their career paths—demonstrates that the musical training of WCM graduates did not necessarily confine them to a singular path. Through the paper trails left by their lives and careers, and by sometimes connecting them to more well-known performers, we can see—and hear—the outlines of their journeys through twentieth-century American musical communities.

1 Jacqueline Moore, Leading the Race: The Transformation of the Black Elite in the Nation’s Capital, 1880-1920 (Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia, 1999), 58-59. The Howard Theatre’s first iteration—established by white entrepreneurs in 1909—was boycotted by Blacks and closed. The second Howard Theatre, owned by the same white entrepreneurs, opened in 1910 as an “optional Jim Crow theatre” and consisted of the white owners “using a black manager as a front.” The owners assumed that African Americans in the vicinity of Howard were “not as comfortably situated” and wouldn’t resist their second offering; yet it still became “the first to claim black management.” Some saw this setup as “succumbing to Jim Crow,” and “many members of the elite preferred to go to downtown theaters…perceiving them as more prestigious” and not wanting “to mix with the working classes.” Still, by 1913, the theater “was widely praised by Washington’s leading black citizens.”

2 Conversation with Dr. Douglas Shadle via Zoom from Northfield MN, July 15, 2022.

3 Ibid.

4 Conversation with Dr. Tammy Kernodle via Zoom from Northfield MN, June 27, 2022. See also Bernice Johnson Reagon, “African Diaspora Women: The Making of Cultural Workers,” Feminist Studies 12, no. 1 (1986): 77–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/3177984

5 Sarah Schmalenberger, The Washington Conservatory of Music and African-American Musical Experience, 1903-1941, 110, 224-242. Although Marshall campaigned intensely to promote black concert music from 1910-22, “no renowned [Black] composer had yet written any piano concertos or sonatas, not even Coleridge Taylor,” which could partially explain the juxtaposition between the majority of white composers performed at the conservatory in this timeframe and Marshall’s mission in founding it.

6 Ibid. Sadly, 5% is still higher than the percentage of works by female composers performed by most symphony orchestras today.

7 Ibid.

8 Washington Bee, Washington, DC, June 5, 1915, pg. 1.

9 Evening Star, Washington, DC, April 30, 1926, pg. 22.

10 Dallas Express, Dallas, TX, January 28, 1922, pg. 3.

11 For Phillips, see Evening Star, Washington, DC, February 6, 1931, pg. 34; Evening Star, Washington, DC, October 31, 1930, pg. 57; New York Times, New York, NY, January 3, 1934, pg. 26; Afro-American, Baltimore, MD, October 10, 1931, pg. 5. For Barrington Guy, see Chicago Defender, Chicago, IL, August 19, 1933, pg. A6; Ibid, August 19, 1933, pg. A6; New York Times, New York, NY, January 12, 1934, pg. 34.

12 Chicago Defender, Chicago, IL, October 17, 1931, pg. 19.

13 The American Musician and Sportsman Magazine, United States: American Music Publishing, 1921, 28. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_American_Musician_and_Sportsman_Maga/GIkyAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1; Washington Conservatory of Music Faculty Listings, Washington, DC, 1903-04, 1904-05, Accessed courtesy of Sarah Schmalenberger, Originally from The Moorland-Spingarn Research Center – Howard University.

14 Journal Herald, Dayton, OH, May 4, 1946, pg. 9.

15 Arthur R. Grant, “Pals First (Will be Pals to the Last” (Worcester, Mass.: Arthur R. Grant Music Co., 1919); Arthur R. Grant, “Dear Mother of Mine” (Worcester, Mass.: Arthur R. Grant Music Co., 1919.

16 Arthur R. Grant, “Dum-Deedle-Dee-Um Dumb Dora” (New York: The Metro Music Co., 1924).

17 Arthur R. Grant, “Bobbsy” (New York: The Metro Music Co., 1923). Bobbsy is an example of another tune by Grant, in addition to It’s a Good Little World After All from “The Logic of Larry,” which we only located the first page from in the Library of Congress. We speculate there are more Arthur R. Grant pieces in existence than we were able to locate in our two months of research.

18Discography of American Historical Recordings, s.v. “Edison matrix 11045. Drifting along (Why don’t you drift home) / James Doherty,” accessed August 3, 2022, https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/matrix/detail/2000157893/11045-Drifting_along_Why_dont_you_drift_home.

19 “It’s Not too Late” was not listed as unpublished, but “Can’t Help Ravin’ ‘Bout My Sex Appeal” was. However, since we couldn’t locate either piece outside of manuscript form, we’ve listed both as unpublished for now.

20 Jewel Jennifer, “It’s Not Too Late” (Washington, DC: Jewel Jennifer Phillips, 1928), accessed July 18 2022, Library of Congress Performing Arts Reading Room.

You must be logged in to post a comment.