Alumni Activists

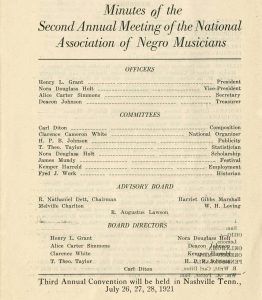

Minutes from second annual convention of NANM, July 1920. Courtesy Florence Beatrice Smith Price Papers Adendum, University of Arkansas Fayetteville Special Collections, MC988a, Box 1, Folder 1, Item 9

In addition to their work as performers and teachers, many early graduates of the Washington Conservatory of Music became activists working with local and national organizations working, most often at the intersection of music and civil rights. Elsie A. Wiggins was active in the NAACP; Henry L. Grant cofounded the National Association of Negro Musicians. This comes as no surprise given that the Washington Conservatory of Music explicitly encouraged race-focused activism. From the outset, Harriet Gibbs Marshall envisioned the Washington Conservatory as an institution that would cultivate “the musical talent of the colored american” and “preserve and develop negro melodies.”1 As such, the Washington Conservatory became a nexus of Black musical activism in the early twentieth century.

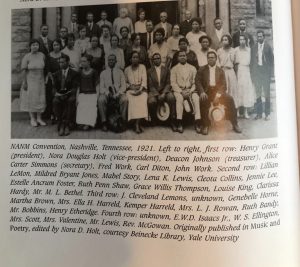

The Washington Conservatory was integrally connected to the organization, development, and founding of the National Association of Negro Musicians (NANM).2 . Not only did 1910 Washington Conservatory graduate, Henry Lee Grant, cofound NANM in 1919 and served as the organization’s first president from 1919-21. Many of the initial meetings for NANM took place at the Washington Conservatory and Gregoria Fraser Goins, who served as the secretary for the Washington Conservatory of Music, also served as the first secretary of NANM.

NANM was conceived as a fellowship network for Black classical musicians. As Doris McGinty points out in her unpublished manuscript on “Artists and NANM,” NANM was built upon pre-existing musical infrastructures created by Marshall, Emma Azalia Hackley, and others, “in a way NANM became an intensification of a process that had started many years before in 1919.”3 NANM was thus one manifestation of a broader phenomenon that Imani Perry has called “Black associationalism,” a trend that saw the proliferation of organizations across every area of civic and professional life.4 Such groups offered networking, political organizing, and business opportunities; they also conferred social status on participants, thus contributing to broader aspirations to racial uplift.5

Local Branches of the National Association of Negro Musicians (NANM) 1919-27. Juxtaposed with 1920 U.S. Census Data Color-Coded by Percentage of African-American Residents.

NANM branch data courtesy of Doris Evans McGinty, ed., A Documentary History of the National Association of Negro Musicians, (Chicago: Center for Black Music Research Columbia College, 2004).

Aside from producing graduates who devoted their time and resources to national activist organizations, the Washington Conservatory was itself engaged in activism: it sought to foster Black music history and culture though the formation of a National Negro Music Center. Harriet Gibbs Marshall began efforts to form a National Negro Music Center as early as 1910.10 By 1931, Marshall was circulating pamphlets that argued, “There is great need of the systematic recording of all facts concerning the history and development of negro music for the American Negro is making musical history.”11 Marshall’s grand vision for a National Negro Music Center encompassed a sheet music library, research department, public performances, and conservatory courses in Black music history.12 To that end, Marshall undertook numerous financial drives trying to secure a $100,000 endowment for the National Negro Music Center in the 1920s and 30s. The correspondence files of the Washington Conservatory of Music Papers at Howard University are full of letters from Marshall soliciting financial support for her National Negro Music Center.13 While much of Marshall’s vision was successful, ultimately Marshall failed to procure her desired $100,000 endowment, and the idea of a National Negro Music Center was not pursued further following Marshall’s death in 1941.14

In retrospect, the Washington Conservatory of Music was a nexus of musical activism. As the first American music conservatory run by Black faculty and designed for Black students, the Washington Conservatory advanced a vision of classical music that centered Black composers and African-American musical history. Washington Conservatory graduates embodied this vision through their organizing work with NANM and in their own communities.

1 Washington Conservatory of Music, School History, Not Dated. Washington Conservatory of Music Papers, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Box 112-53, Folder 9.

2 The definitive secondary source on the National Association of Negro Musicians is Doris Evans McGinty, ed., A Documentary History of the National Association of Negro Musicians, (Chicago: Center for Black Music Research Columbia College, 2004).

3 “Artists and NANM First Draft (June 1996),” Doris McGinty Papers, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Box 45-16, Folder 38, pg. 52.

4 Imani Perry, May We Forever Stand: A History of the Black National Anthem (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 6.

5 Jarvis Givens, Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021, 54.

6 “Minutes of the Second Annual Meeting of the National Association of Negro Musicians July 1920,” MC988a, Box 1, Folder 1, Item 9, Florence Beatrice Smith Price Papers Adendum, University of Arkansas Fayetteville Special Collections, https://digitalcollections.uark.edu/digital/collection/p17212coll3/id/32.

7 Chicago Defender, Chicago, IL, September 10, 1927, pg. 7.

8 Ibid.

9 New Journal and Guide, Norfolk, VA, August 29, 1931, pg. 5.

10 The 1910-11 Washington Conservatory of Music School Catalogue listed a goal of the school as “The Preservation of Negro Melodies,” Washington Conservatory of Music Papers, Box 112-54, Folder 35, Scrapbook 3, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

11 Washington Conservatory of Music Papers, Box 112-3, Folder 117, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

12 Ibid.

13 See Washington Conservatory of Music Papers. https://dh.howard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1220&context=finaid_manu.

14 More research would be needed to determine whether Marshall’s vision inspired similar efforts by later scholars, notably Eileen Southern and Samuel Floyd, Jr., to create Black music research centers like the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library and the Center for Black Music Research in Chicago.

You must be logged in to post a comment.