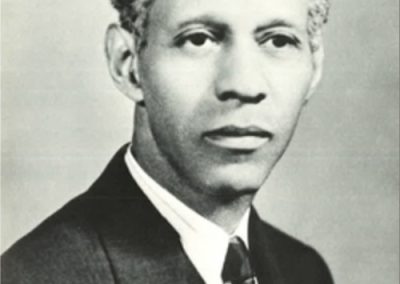

Alumnus Spotlight: Henry Lee Grant

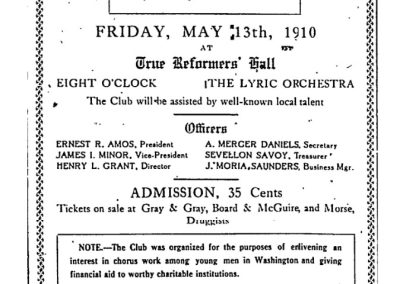

One early standout graduate from the Washington Conservatory was Henry Lee Grant (1886-1954). Grant’s career as a teacher at Dunbar High School, role as president and founder of the National Association of Negro Musicians (NANM), and work as a composition teacher to Duke Ellington established Grant as a major musical influence in early twentieth-century Washington, DC. Grant was among the eleven inaugural graduates of the Washington Conservatory, completing the Artists Course with degrees in piano and theory in 1910.1 After graduation, Grant taught piano and harmony at the Washington Conservatory from 1910-13, where he initially received a salary of $40.00 per month.2 During Grant’s time on the faculty at the Washington Conservatory, Grant also directed two Washington, DC based musical ensembles: Will Marion Cook’s Afro-American Folk Song Singers, and the L’Allegro Glee Club. The Afro-American Folk Song Singers were a Washington, DC based choral ensemble started by composer, violinist, and conductor Will Marion Cook. Grant assumed directorship of the organization around 1919, when Cook led the Southern Syncopated Orchestra on its groundbreaking tour of Europe. Grant established the L’Allegro Glee Club in 1909 and the group performed frequently in Washington, DC. Both ensembles gave Grant a platform to exercise musical leadership and present programs focused on music by Black composers.

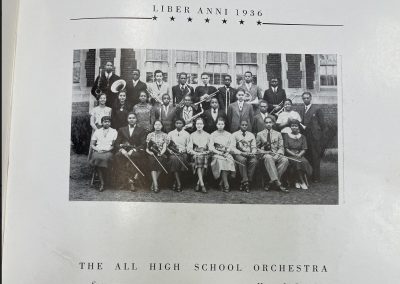

In 1917, Grant accepted a position teaching music at Dunbar High School. Grant remained at Dunbar for thirty-five years until his retirement in 1952. In 1919, Grant founded the Dunbar High School Orchestra, a multifaceted ensemble that promoted social activism through public performance. The history of the Dunbar High School Orchestra was memorialized in the 1936 Dunbar High School yearbook: “The high school orchestra idea began its career in Dunbar High School in 1919 as an extracurricular activity under the direction of Mr. Henry L. Grant. Because of its services rendered to the school, it soon became an indispensable part of the musical department for which much credit was given.”3 The Dunbar High School Orchestra also participated in multiple public performances meant to showcase Black musical talent and musical history. In July 1923, “a large chorus of students led by Henry L Grant” presented “a pageant adapted from Booker T. Washington’s Up From Slavery” at the Hampton Institute.4 While, in 1926, the Dunbar High School orchestra performed “a program of Negro music at the Philadelphia Sesquicentenial on Monday, August 23.”5

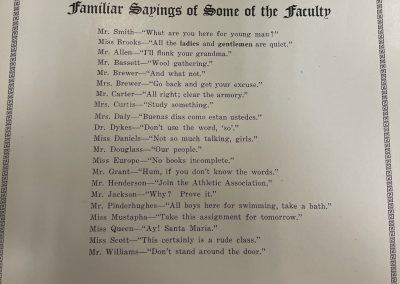

By the 1920s, Grant was a well-liked and sought after music teacher in Washington, DC. In the 1925 Dunbar High School yearbook under the heading “Familiar Sayings of Some of the Faculty” Grant was characterized with the pedagogical epithet: “Hum if you don’t know the words.”6 At the time of his retirement on September 30, 1952, the DC Board of Education listed Grant as a teacher under salary class 3A making $4,653 per year, which is over $52,000 in 2022.7

L’Allegro Glee Club Advertisement

L’Allegro Glee Club Advertisement. Washington Bee, Washington, DC, May 7, 1910, pg. 8

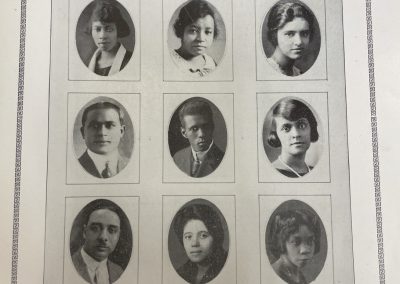

Dunbar HS Faculty

Henry L. Grant, faculty photo. Dunbar High School Yearbook, 1925. Grant is in the center in the third row from the top. Courtesy of Sumner School Museum and Archives, Washington, DC.

All School Orchestra

The 1936 All School Orchestra. Courtesy of Sumner School Museum and Archives, Washington, DC.

Dunbar Faculty Sayings

Familiar Sayings of Some of the Faculty, Dunbar High School Yearbook 1925, Courtesy of Sumner School Museum and Archives, Washington, DC.

Outside of his work at Dunbar High School, Grant also gave private composition lessons to a teenage Duke Ellington. In his dissertation on Ellington, Mark Tucker recounts that Ellington studied with Grant about twice per week. Tucker argues, “Grant was a new kind of teacher for Ellington. He was not only a versatile musician who composed, conducted, and concertized as a pianist, but also an active promoter of Negro music.”8 The musicologist Doris McGinty recounted interviews with Grant’s daughter June Hackney, writing: “It was a source of amusement to her that Grant was able to point out wrong notes and even incorrect fingerings on the part of the young pianist even in instances when he could hear the piano but was actually out of the room.”9 McGinty further characterizes Grant as a musician who was interested in both classical and popular music, stating: “Grant and Ellington became fast friends, and in 1952, according to Grant’s daughter June, Ellington, wishing to repay the educator who had just retired, took Grant along on a tour to St. Louis and points west.”10

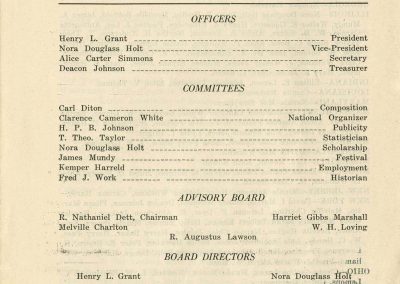

As a musician and activist [link to Activism page], Grant also played a pivotal role in founding the National Association of Negro Musicians (NANM). Grant served as the first president of NANM from 1919-21 and edited NANM’s journal The Negro Musician. Connecting his teaching career with his activism, Dunbar High School sponsored the first meeting of the National Association of Negro Musicians.11 While officially organized in the spring of 1919, efforts to found a national organization of Black classical musicians began as early as 1906. Grant’s large musical network in Washington, DC and beyond provided the connections and and fostered the leadership skills to successfully found NANM. At the first annual conference in 1920, The Washington Herald reported, “Henry L. Grant spoke of the community’s part and said that negro musicians should take an interest in the development of community music, for it made for character and ideals.”12 Of NANM’s mission and goals, musicologist Doris McGinty wrote, “It was their intention that NANM would be, above all, a touchstone for hundreds engaged on various levels and in various categories of activity associated with music, and, it was their hope that with assistance from NANM and the stimulation of increasing opportunities for education, world class artists would emerge from the ranks.”13 [Minutes from second annual convention of NANM, July 1920. Courtesy Florence Beatrice Smith Price Papers Adendum, University of Arkansas Fayetteville Special Collections, MC988a, Box 1, Folder 1, Item 9.]

As a music educator and organizer, Henry L. Grant played a major role in early twentieth century Black musical networks in Washington, DC. At Dunbar High School, Grant influenced countless young musicians. As president and founder of NANM, Grant led the first professional network of Black musicians. While today, Grant is overshadowed by his more famous NANM co-founders, Nora Douglas Holt and Clarence Cameron White, Grant arguably did more to advance twentieth century Black musical education and organizing.

Mapping Hometowns, Primary Residence Locations, and Death Locations of Washington Conservatory Graduates

Like most graduates of the Washington Conservatory, Henry L. Grant was born in Washington, DC. Grant spent the remainder of his life in Washington, DC and died in Washington, DC in 1954. The following map visualizes hometowns, primary residence locations, and death locations of Washington Conservatory residents scaled by frequency of data. Each variable is visualized in a separate map. Click through to view each map.

While Washington, DC has the most data in all three maps, graduates came from a greater variety of hometowns compared to primary residence locations and death locations.

1 First Commencement Program, June 3, 1910. Washington Conservatory of Music Papers, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Box 112-52, Folder 21.

2 “School Proceedings Contracts A-M,” Washington Conservatory of Music Papers, Box 112-11, Folder 229, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

3 Dunbar High School 1936 Yearbook, pg. 77, Courtesy of Sumner School Museum and Archives, Washington, DC.

4 Broad Axe, Chicago, IL, July 14, 1923, pg. 3.

5 New York Age, New York, NY, August 21, 1926, pg. 5.

6 Dunbar High School 1925 Yearbook, Courtesy of Sumner School Museum and Archives, Washington, DC.

7 Washington, DC Board of Education Minutes, October 15, 1952, pg. C-1, Courtesy of Sumner School Museum and Archives, Washington, DC.

8 Mark Tucker, “The Early Years of Edward Kennedy ‘Duke’ Ellington, 1899-1927,” PhD Diss, University of Michigan, 1986, 133.

9 “Artists and NANM First Draft (June 1996),” Doris McGinty Papers, Box 45-16, Folder 38, pg. 46, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

10 Ibid.

11 Dunbar High School Music Festival Program, May 1919, Gregoria Fraser Goins Papers, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Box 36-7, Folder 88.

12 Washington Herald, Washington, DC, August 15, 1920, pg. 25.

13 “Artists and NANM First Draft (June 1996),” Doris McGinty Papers, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Box 45-16, Folder 38, pg. 46.