Teachers have lives outside of school? Children may not understand the extent to which teachers, like Elsie Wiggins, can be deeply involved in their community. Elsie Adele Wiggins (1896-1963) was a teacher and activist in early twentieth-century Washington, DC. As a teacher at seven different Washington, DC elementary schools, Wiggins influenced the lives of hundreds of young students. Almost all Washington Conservatory graduates from 1910-1914 became teachers. Still, few we know of were as active in civic circles as Wiggins. Investigating Wiggins’ biography illustrates that her teaching career and advocacy for social causes outside the classroom significantly strengthened the fabric of Black communities.

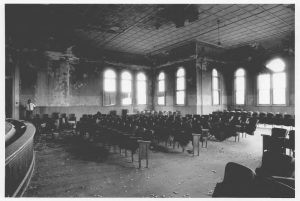

M Street High School auditorium, July 1986. Wiggins graduated from here in 1915. Photograph by Patricia Fisher, National Register of Historic Places Collection, https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/AssetDetail/c3449d06-85a3-4b61-b06f-8fd3b9b1bbc9.

Wiggins was born in Washington, DC, in August 1896 to J. Douglas Brown, a hotel bellman, and Adelle M. Brown, who did not work.1 Though Wiggins’ parents were not members of the Black elite, her academic career reflects the racial uplift value of education.2 She graduated from the advanced course at the Washington Conservatory in 1912 before obtaining her diploma from M Street High School in 1915.3 Like other Washington Conservatory graduates, she sought post-secondary education, graduating from Miner Normal School’s kindergarten department course in 1917.4 This path led Wiggins to her teaching career during a time when a significant number of Black women became teachers who impacted their communities.5

Wiggins, in particular, impacted many communities as she taught at seven different schools across Washington, DC, throughout her thirty-year career. She put her kindergarten degree from Miner Normal School to use, teaching kindergarten at the Stevens School (1917-18), Langston School (1918-1921), and the Garnet-Cleveland School (1923-unknown).6 Wiggins would go on to teach primary grades at the Cleveland School (1928-unknown), Logan School (unknown dates), Walker School (unknown dates), and the John F. Cook School (1940-1946).7 While at the Cleveland School, Wiggins also served as a representative on a committee to revise the fifth-grade history curriculum during the 1928-29 school year.8 [Cleveland School photo]

Stevens School, April 2001. Wiggins taught kindergarten here from 1917-1918. Photograph by Tanya Edwards Beauchamp, National Register of Historic Places Collection. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/AssetDetail/812ea738-a29d-4de5-be6b-7691c4f6ef02

A lack of documentation leaves questions in the chronology of Wiggins’ teaching career, yet she unquestionably influenced the communities surrounding each school. Her retirement approval note from the Washington DC Board of Education characterizes Wiggins as “a conscientious, dependable teacher with high ideals… Mrs. Wiggins has won many friends by her cheerful and willing cooperation in the school and community.”9 Such a testament to Wiggins’ teaching speaks to the significance she held to the communities in which she taught.

Teaching was but one of the spheres of influence through which Wiggins spread her cheerful cooperation in Black Washington, DC. Wiggins spent her life in community groups with focuses ranging from literacy to racial progress. Her obituary lists her as having been active in “the Urban League, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Women’s Civic Guild, the Board for Mentally Retarded Children, the United Church Women, United Givers Fund, and both the Heart and Cancer Funds.”10 Wiggins also served as a board member for the James Weldon Johnson Literary Guild, through which she helped organize an event with famed contralto Marian Anderson.11 Training from the Washington Conservatory, whose stated goals included race-focused activism, undoubtedly was formative in Wiggins’ advocacy work.

1944 Washington, DC NAACP Membership Drive winning team. Wiggins is in the second row, third from the right. “Winning Team in NAACP Membership Drive,” The Chicago Defender (National edition) (Chicago, IL, April 8, 1944), 14.

Wiggins’ contributions to social causes were recognized on a city-wide level. Washington, DC chapters of the NAACP held a membership drive competition in 1944. Wiggins’ chapter, based at Plymouth Congregational Church, was victorious with 1,100 members and $1,500 (about $25,250 today).12 There is perhaps no greater testament to Wiggins’ legacy as a civic leader than the size of her NAACP chapter: a community grounded in shared dreams of racial equity. Even in the final years of her teaching career, Wiggins was concurrently active in Black activist circles through numerous organizations. Ultimately, Wiggins’ dedication to her students and community strengthened the fabric of Black communities.

1 Year: 1900; Census Place: Washington, District of Columbia; Roll: 160; Page: 19; Enumeration District: 0044; FHL microfilm: 1240160.

2 Kristen M. Turner, “Class, Race, and Uplift in the Opera House: Theodore Drury and His Company Cross the Color Line,” Journal of Musicological Research 34 (2015): 338, https://doi.org/10.1080/01411896.2015.1082380.

3 “Nine Receive Diplomas,” Evening Star, (Washington, DC, June 16, 1912), 12; “Urged to Share in World’s Work,” Evening Star, (Washington, DC, June 22, 1915), 5.

4 “Miner Normal School Confers Diplomas,” Evening Star (Washington, DC, June 15, 1917), 4.

5 Doris Evans McGinty, “‘As Large as She Can Make It’: The Role of Black Women Activists in Music, 1880-1945,” in Cultivating Music in America: Women Patrons and Activists since 1860, ed. Ralph P. Locke and Cyrilla Barr (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1997), 218. For statistics on gender demographics among Black teachers in 1900 and 1910, see Jarvis Givens, Fugitive Pedagogy, 83.

6 District of Columbia Board of Education, “Minutes of the Eleventh (Stated) Meeting of the Board of Education, February 1, 1950,” in Minutes of the Board of Education of the District of Columbia, Feb. 1, 1950 to April 5, 1950, vol. 68 (Washington, DC, 1950), 33.

7 Ibid.

8 District of Columbia Board of Education, Report of the Board of Education of the District of Columbia, 1927-1928 (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1928), 75.

9 District of Columbia Board of Education, “Minutes of the Eleventh (Stated) Meeting of the Board of Education, February 1, 1950,” in Minutes of the Board of Education of the District of Columbia, Feb. 1, 1950 to April 5, 1950, vol. 68 (Washington, DC, 1950), 33.

10 “Mrs. Elsie A. Wiggins, 62, Teacher and Civic Leader,” Evening Star, (Washington, DC, May 21, 1963), B-5.

You must be logged in to post a comment.