Harriet Gibbs Marshall: Founder, Impresario, Frustrated Visionary

The story of the Washington Conservatory of Music is inextricable from that of its founder, Harriet Gibbs Marshall. The first Black woman to receive a music degree from Oberlin Conservatory and the scion of the wealthy, influential Gibbs family, Marshall led the conservatory from its founding in 1903 through her death in 1941.1 She served as the institution’s president, chief fundraiser, biggest donor, and publicist. As evidence of her status as a visionary, she conceived of the conservatory—already a massive undertaking—as just one piece of a larger project to establish a National Negro Music Center that would become a clearinghouse for research on, performance of, and education in Black music. Despite her best efforts, Marshall never raised enough money to launch the center in the way she had envisioned. But, as our research has shown, Marshall’s energy, advocacy, and strategic vision bore fruit as graduates of the Washington Conservatory spread across the country, carrying the spirit of her project into communities far from Oberlin and Washington, DC.

Marshall was a part of an extremely influential and wealthy family that holds their roots in the South, specifically Kentucky.2 Her parents, Maria Alexander Gibbs and Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, encouraged both their children, Ida and Harriet, to attend college and get out of the South before marrying.3 Education was extremely important to the family as a whole. So much so that Maria’s family (Harriet’s grandparents) moved to Oberlin, Ohio, in 1852 so that she and her four sisters could all be enrolled into a northern institution.4 That encouragement didn’t stop with Maria’s parents, but rather extended through to her children and in turn, her grandchildren. Harriet, one of those grandchildren, garnered a music degree from Oberlin Conservatory, the first Black woman to do so, and studied in Europe as well5(Clarence Cameron White, who taught at the Washington Conservatory from 1903-1907, mentioned Gibbs Marshall’s European performances in his article “The Negro in Musical Europe.”6). While her siblings may have dabbled in music, Harriet was the only one to dedicate her life to it. She spent time in Kentucky, landing a teaching position at Eckstein-Norton University, a Baptist school, which helped develop the skills she’d use to open the Washington Conservatory of Music.7

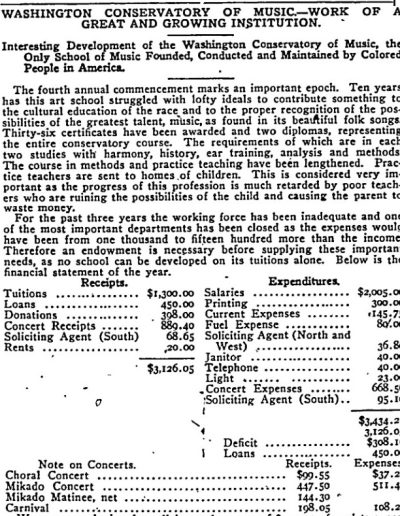

Marshall dealt with many challenges as she worked tirelessly to keep her Conservatory in business. Finances, for example, were an issue that took up a lot of her time. It seemed like she was always writing letters to encourage donations, and for good reason. This is a newspaper clipping outlining the expenses of the Conservatory in 1913. Marshall had a $308.16 deficit this year, which was not uncommon.8Another challenge, of course, was the racial climate within which Marshall and her students were steeped. In leading this Conservatory, Marshall carried a burden that was not just relegated to financials and advertisement. She also had to be conscious of how she was presenting her race. Racial uplift was a major ideology of the time, championed by W.E.B. Dubois, and education was one of the key ways he was pushing to achieve this.9 Concert programming proved to be one area in which Marshall manifested ideals of racial uplift: Washington Conservatory programs presented Classical music by white and Black composers, the latter of which were (justifiably) overrepresented relative to their population. Concert spirituals played a more complicated role in uplift efforts. To white audiences, spirituals were growing in popularity; their reception was much more mixed among Black audiences.10 This was in part thanks to the Fisk Jubilee Singers and other groups like them. Marshall took this to heart, putting some Concert Spirituals in the repertoires her students performed along with music written or composed by Black musicians. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, for example, was frequently played in performances and is featured many times in programs, made clear by the number of times his pieces appear in this Spotify playlist which presents some of the music performed at the Conservatory.11 Still, the majority of the music that was played was composed by white men. For more information on Washington Conservatory performances and composers, visit our Alumni in the Concert Hall page.

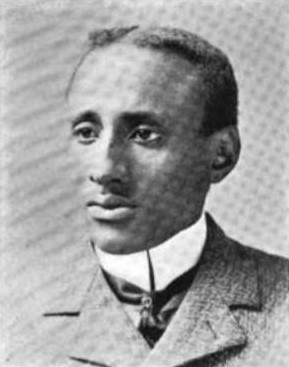

Harriet Gibbs Marshall

Harriett Gibbs Marshall Photo Credit: Maud Cuney-Hare. Negro Musicians and Their Music. New York: Da Capo Press, 1974.

Harriet Gibbs Marshall ran the Washington Conservatory of Music for almost 40 years until her death in 1941. However, she took a brief intermission from her leadership there in the 1920s when she traveled to Haiti with her husband, Napoleon Bonaparte Marshall.12 She lived there for six years, and settled into a new leadership role when she established a girls’ vocational school. Marshall had returned to her Conservatory by 1930.13 In some ways, Marshall’s original vision for the school was lost when she was succeeded by Josephine Muse after her death. One of Marshall’s key goals was to make the school a ‘Black Oberlin,’ but she was never able to reach that goal as outside factors like the Great Depression, two World Wars, and the general pragmatism of racism greatly affected the school.14 There was also a major shift in what songs were performed. For most of Marshall’s tenure, she included Black pieces, including spirituals and concert works composed by Black composers.15 What with her visions of creating a National Negro Music Center, this push for Black music makes sense.16 Josephine Muse, however, did not share this same vision. Muse shifted the repertoire of her students drastically, having them perform almost solely white Western Classical music.17 As Sarah Schmalenberger writes, “It would appear that Marshall’s hopes and ambition to cultivate a black musical aesthetic died with her.”18

Marshall had big dreams and was a very ambitious woman. For example, she didn’t just make history as the first Black woman to graduate from Oberlin Conservatory in music—she was also the second Black American to join the Bah`a’i faith, and held many meetings for the members of the religion in the Conservatory.19 When she left the school to go to Haiti, she didn’t just take a long vacation. Instead, she learned a lot about Haitian culture there, and ultimately wrote a book about Haiti when she returned to the states.20

Really, she learned a lot about Haitian tourist culture, and not about anything that was realistic to the Haitian people, but she still did enough research and committed to publishing The Story of Haiti.21 As is clear from the correspondence preserved in the Washington Conservatory of Music collection at Howard University’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Marshall consistently advocated for the Haitian cause. Her ambition never faded, as evidenced by her continued attempts to fundraise for the National Negro Music Center up to her death in 1941.

Harriet Gibbs Marshall was a musician, director, fundraiser, donor, and publicist—but the real measure of her success can be found in the countless students whose lives she touched. Those students have long constituted the “anonymous infrastructures” that Howard University musicologist Doris McGinty posited as a crucial part of Black musical communities in this country.22 Our project furthers Marshall’s legacy by giving names to the musical networks she fostered all across the country—and across time.

1 Sarah Schmalenberger, The Washington Conservatory of Music and African-American Musical Experience, 1903-1941, 1.

2 Sarah Schmalenberger, 15.

3 Phylicia Fauntleroy Bowman, “Phylicia Fauntleroy Bowman: Oral History Interview,” by Dr. Louis Epstein et al., Musical Geography Project, July 6, 2022, 3.

4 Schmalenberger, 15-16.

5 Schmalenberger, 24.

6 Clarence Cameron White, “The Negro in Musical Europe,” New York Age, December 24, 1908, 13. See also Kira Thurman, Singing Like Germans: Black Musicians in the Land of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2021).

7 Schmalenberger, 25.

8 “Washington Conservatory of Music–Work of a Great and Growing Institution”, The Washington Bee (Washington, DC, June 14, 1913), 8

9 Schmalenberger, 7.

10 Schmalenberger, 118-119.

11 Schmalenberger, 108.

12 Schmalenberger, 175-176.

13 Ibid.

14 Personal conversation with Sarah Schmalenberger, June 20, 2022, Mendota Heights, MN.

You must be logged in to post a comment.