A Black Conservatory in a Segregated Nation

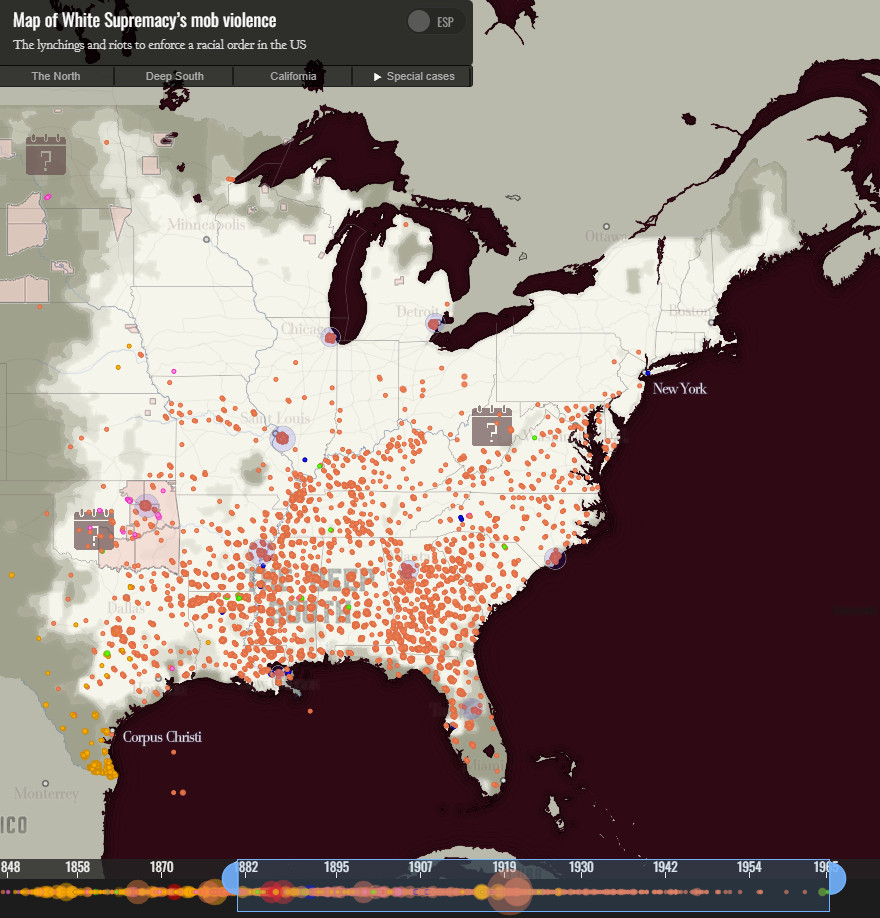

The thirty musicians who graduated from the Washington Conservatory of Music between 1910 and 1914 lived during a particularly turbulent time in American history. Born after the end of Reconstruction, they participated in the rapid growth of the Black middle and upper class. 1 At the same time, the communities they lived in suffered white supremacist backlash in the form of racist laws and court decisions that established what became known as “Jim Crow” segregation. 1915 saw the release of Birth of a Nation, a wildly popular film that celebrated the Ku Klux Klan and arguably marked the high point of that group; 1915 was also the year that many scholars have identified as the start of the Great Migration, which saw millions of Black Americans flee the violence and discrimination of the South for opportunity in the North, which had its own form of Jim Crow segregation.2 Maps help tell the story: while Black Americans living in the South were far more likely to face violence, including lynchings, in the North they encountered racial covenants and redlining practices, which limited the accumulation of generational wealth in ways that continue to affect Black communities today.

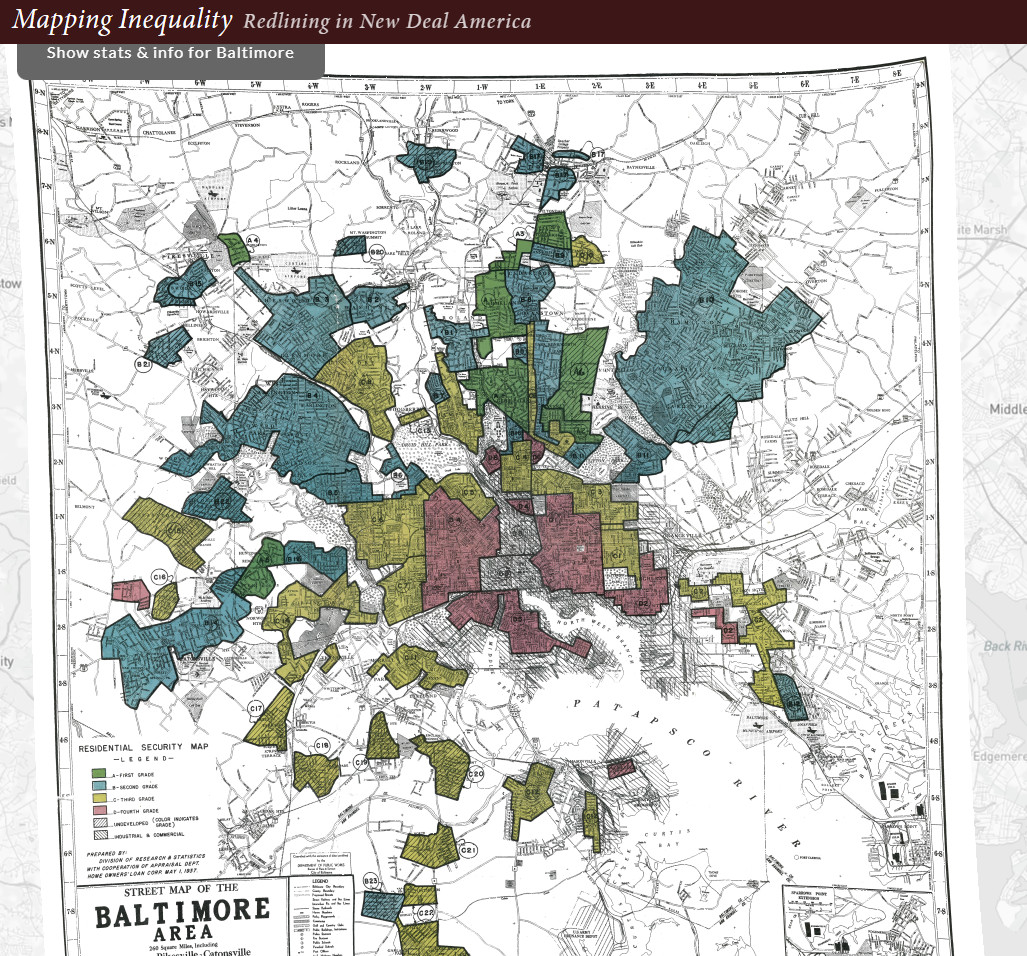

The Home Owners Loan Corporation created maps of hundreds of US cities in 1937 that graded neighborhoods on the basis of whether they were “safe investments” for mortgage companies. Black neighborhoods were systematically labeled as unsafe, and property values in these neighborhoods suffered as a result, often for generations. Click the map to access the interactive maps through the Mapping Inequality project.

This map, part of the Monroe and Florence Work Today website, shows the locations of racially-motivated lynchings in the Eastern United States between 1880 and 1965. Click the image to access an interactive version of this map.

Musically, too, the early twentieth century saw uneven gains for Black Americans, particularly in the realm of classical music. A few groups and figures – the Fisk Jubilee Singers, Sisierietta Jones, Roland Hayes, Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson – earned international stardom. Many more Black musicians performed widely in the United States and in Europe without becoming household names.3 At the same time, numerous barriers remained, particularly in the South and on some of the nation’s most illustrious stages: Marian Anderson’s 1939 performance at the Lincoln Memorial came after the Daughters of the American Revolution denied her the opportunity to perform at Constitution Hall, and it was only in 1955 that Anderson integrated the stage of the Metropolitan Opera – in the blackface-adjacent role of the witch Ulrica in Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera.4 While some historically white conservatories accepted Black students – Sisierietta Jones, Mary Cardwell Dawson, and Florence Price studied at the New England Conservatory; Marian Anderson at Curtis; R. Nathaniel Dett, Will Marion Cook, and William Grant Still at Oberlin – these were exceptions that proved the rule.5 Most schools, concert halls, ensembles, management agencies, and other music institutions remained segregated and deliberately excluded Black musicians.

It was in this context that Harriet Gibbs Marshall founded the Washington Conservatory. Given her family background and her connections with W.E.B. DuBois and other Black intellectuals, it is hardly surprising that the Washington Conservatory preached the gospel of racial uplift.6 Around the turn of the century, many Black elites believed that cultivating Black excellence would force white Americans to acknowledge the social and, eventually, legal equality of Black Americans. Along these lines, DuBois developed the idea of the “Talented Tenth,” a Black upper class that would improve the lives of those less fortunate through achievement and recognition.7 In her fundraising efforts, Gibbs Marshall referred to the institution she had founded as “the first conservatory of music of the race,” which likely carried a double meaning: it was the chronological first, but it was also intended to be the best.8 The conservatory quickly became a beacon for aspiring Black musicians throughout the country.

While racial uplift was a priority for many Black musical initiatives in the early twentieth-century,9 it would be reductive to suggest that it was the only or even the main priority. Education scholar Jarvis Givens has argued that we might understand turn-of-the-century Black education in terms of “fugitive pedagogy,” in which Black teachers (mostly women) evaded and subverted the erasure of Black histories and accomplishments from US American curricula. Black educators, Givens writes, “understood their teaching and learning to be perpetually taking place under persecution, even as they created learning experiences of joy and empowerment.”10 That from its beginnings the Washington Conservatory served an ideological purpose – to preserve and promote Black music and musicians – is already clear from the preponderance of Black composers on the programs of Washington Conservatory concerts and from the fact that all teachers at the conservatory were Black (which was not the case at many HBCU music programs in the early twentieth century). When Harriet Gibbs Marshall sought to create the National Negro Music Center, which had a goal of collecting and preserving published music by Black composers from around the world – the institution further embraced what Givens calls “the transgressive nature of [Black] education.”11

Another priority, one emphasized by Dr. Phylicia Bowman in the oral history she provided of the Gibbs family (of which she is a descendant), represented a different kind of transgression. In her telling, the Black musicians who attended and taught at the Washington Conservatory – like Black professionals more broadly – pursued music at high levels because music was where they found their purpose. Like any institution of higher learning, the Washington Conservatory was a place for normal people pursuing gratifying careers that leveraged their talents and that addressed some need in the world. In that same Mary Church Terrell invocation, the rationale for the conservatory’s establishment is that “the colored people of the United States possess a remarkable talent for music,” and “this talent should be developed in every way and to the highest degree.”12 In other words, Black musicians deserve and need training, so they shall be trained.

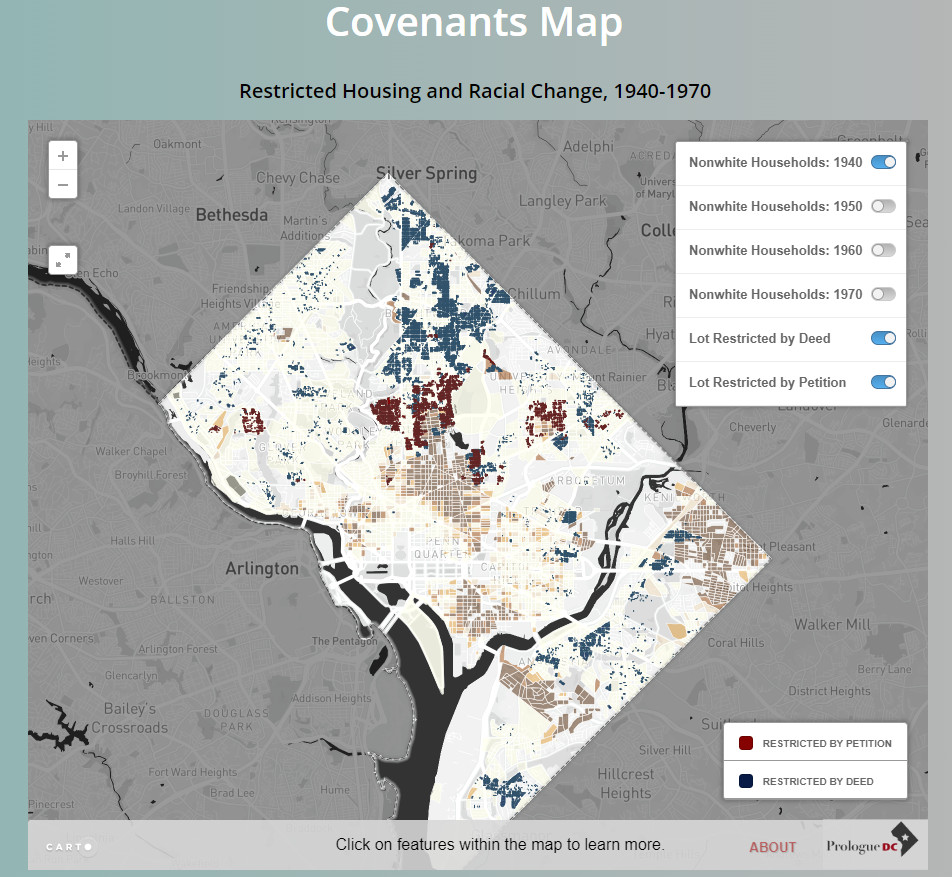

Whatever reason Washington Conservatory graduates chose to pursue music, they could not avoid the oppressive politics imposed by white supremacy at every level of government. The conservatory sent graduates to teach at places like Dunbar High School in Washington, DC and numerous HBCUs, all of which received fewer resources and less support from the state than did historically white institutions. Despite being a prosperous cultural mecca, the Shaw neighborhood in DC (the Washington Conservatory’s home) fell victim to redlining toward the end of Marshall’s tenure as the school’s director. The Federal Housing Authority graded the historically Black neighborhood under the category “F – rapidly declining,” causing home values to plummet and leading to later decisions to engage in urban renewal projects that displaced thousands of Black families. You can explore redlining in DC using the map on the left below, created by the Mapping Segregation DC project to show how the Federal Housing Administration raised homeownership rates and generational wealth for white families while making in more difficult for Black families to buy and maintain homes. Compare the FHA grading map on the left with the map on the right, which shows residences of Washington Conservatory graduates during and after their time at the institution. It’s striking to see how the federal government essentially doomed a thriving section of DC where many Washington Conservatory students lived and worked.

Discrimination and dispossession contributed to the seething resentment that fueled the 1968 Washington, DC uprising, during which the Shaw neighborhood was badly damaged. Howard Theatre – the site of the Washington Conservatory’s second commencement ceremony in 1911 – closed shortly after the uprising, in 1970. And the uprising was only an echo of previous waves of violence that upended the lives of Washington Conservatory graduates: In 1917, while serving as Director of Music at Lincoln High School, Daisy Westbrook’s home in East St. Louis, IL was looted and burned by white rioters intent on destroying a prosperous Black community. According to a letter she wrote to a friend, Westbrook was lucky to escape with her life.13 Scholars believe approximately 100 Black residents lost their lives during the race riot.14

Segregationist and white supremacist policies operated as significant brakes on the momentum of the Washington Conservatory during its half-century existence, not to mention on the students it trained and graduated. But by better understanding how the conservatory and its students flourished despite the obstacles they faced, as we seek to do in this project, we stand to develop a much more complete picture of the ways Black classical musicians contributed and responded to the musical, political, and social fabric of twentieth-century American life.

1 Sarah Schmalenberger, See Elizabeth Dowling Taylor, The Original Black Elite: Daniel Murray and the Story of a Forgotten Era (New York: HarperCollins, 2017); Willard Gatewood, Aristocrats of Color: The Black Elite, 1880-1920 (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991); Jacqueline Moore, Leading the Race: The Transformation of the Black Elite in the Nation’s Capital, 1880-1920 (Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia, 1999).

2 Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration,

3 Kira Thurman, Singing Like Germans: Black Musicians in the Land of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2021). You can find maps of tours and performance venues for some of these musicians at https://musicalgeography.org/project/the-life-and-legacy-of-h-t-burleigh-1866-1949/.

4 Carol Oja, “Marian Anderson and the Desegregation of the American Concert Stage,” paper delivered at St. Olaf College, April 2018. An earlier version of the talk is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LHB98VcB7So.

5 To learn more where the Black musical elite received their educations in the early twentieth century, see Maud Cuney Hare, Negro Musicians and their Music (Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1936).

6 On racial uplift, see Kevin K. Gaines, Uplifting the Race: Black Leadership, Politics, and Culture in the Twentieth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996); and Wilson Jeremiah Moses, The Golden Age of Black Nationalism, 1850-1925 (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1978).

7 The term “talented tenth” emerged among white Northern Liberals in the mid-1890s who were intent on creating institutions of higher education in the south to educate Black Americans. It was popularized by W.E.B. DuBois in an essay, “The Talented Tenth,” published at the same time as the Washington Conservatory’s founding. See Booker T. Washington, et al., The Negro Problem: a series of articles by representative American Negroes of today (New York: James Pott and Company, 1903). The essay is available online at https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/the-talented-tenth/.

8 Harriet Gibbs Marshall, campaign letter for the National Negro Music Center, Washington Conservatory of Music Collection, Howard University Moorland-Spingarn Research Center.

9 See especially Kristen Meyers Turner, “Class, Race, and Uplift in the Opera House: Theodore Drury and His Company Cross the Color Line,” Journal of Musicological Research 34 (2015): 320-351; and on Harriet Gibbs Marshall’s reliance on rhetorics of uplift during her directorship of the Washington Conservatory, see Sarah Schmalenberger, “Shaping Uplift Through Music,” Black Music Research Journal 28, no. 2 (Fall 2008): 57-83.

10 Jarvis Givens, Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2021), 8.

11 Ibid., 9. Along similar lines, Sarah Schmalenberger has argued that Gibbs Marshall’s “work as an institution builder was a form of resistance, generated from within a cultural milieu that had long been the exclusive domain of Anglo-European white male practitioners.” Schmalenberger, “Shaping Uplift Through Music,” 58.

12 Mary Church Terrell, “The Washington Conservatory of Music for Colored People and Its Teachers,” Voice of the Negro (November 1904): 525-530, 525.

13 Daisy Westbrook, Letter to Louise Madella, July 19, 1917, in Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Society, 1972), 328-30, reprinted in Letters of the Century America 1900-1999, edited by Lisa Grunwald Alder and Stephen J. Alder (Dial Press, 1999), 116-118.

14 See Allison Keyes, “The East St. Louis Race Riot Left Dozens Dead, Devastating a Community on the Rise,” Smithsonian Magazine, June 30 2017, accessible at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/east-st-louis-race-riot-left-dozens-dead-devastating-community-on-the-rise-180963885/.