Alumna Spotlight: Wilhelmina B. Patterson

Patterson circa 1920. Courtesy of Dale-Patterson Family Collection, Box 8, Folder 23, Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum.

Wilhelmina B. Patterson (1888-1962) was a highly regarded music educator, vocalist, and pianist in early twentieth century Washington, DC and beyond. As a faculty member at multiple Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) including Prairie View A&M and Hampton University, Patterson influenced countless young musicians. Parsing Patterson’s biography through digitized newspapers, census records, and archival sources, it is clear that the Washington Conservatory of Music played a major role in shaping early twentieth century Black music educators.

Wilhelmina B. Patterson at the Hampton Institute circa 1922. Patterson is second from right in the first row and is standing. Courtesy of Dale Patterson Family Collection, Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum, Box 8, Folder 24

Patterson was born in Calvert, Texas on June 23, 1888.1 By 1900, the Patterson family was living in Washington, DC at 1214 Linden St, NE.2 Patterson, who was known as Bessie to her friends and family, graduated from the Washington Conservatory of Music in the Artists Course for Piano and Theory in 1911.3 When Harriet Gibbs Marshall (1868-1940) founded the Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression in 1903, one of her goals for the school was “the thorough training of gifted negroes who will use negro music in education institutions, especially in the southern states.”4 Patterson fulfilled this objective by first directing the music department at Prairie View State Normal Institute (now Prairie View A&M) from 1911-16, and then teaching at the Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) from 1916-34. At Hampton, Patterson directed the Girl’s Glee Club and also taught music at Phenix High School, a training school for Hampton students studying education located on the Hampton Campus. By early 1934, however, Patterson was forced to resign from her position at Hampton due to administrative reorganization.

Letters and newspaper accounts indicate Patterson was a well-liked and popular faculty member at Hampton during the 1920s. In 1921, Hampton President James E. Gregg wrote to Washington Conservatory Founder Harriet Gibbs Marshall, “With regard to Miss Patterson I am happy to say that her services here have given pleasure and satisfaction to everyone. She is modest and engaging in her personality, knows how to do her work through really well and has the faculty of getting on happily with other people. We are very glad that we have her at Hampton.”5 Under Patterson’s direction, the Hampton Girl’s Glee Club performed frequently. In an attempt to solicit performance opportunities for the Glee Club, Patterson wrote to Harriet Gibbs Marshall in 1931: “They are about forty in number and could give a very interesting recital, of accompanied and unaccompanied numbers, including negro spirituals by Burleigh and Dett, Indian songs, French songs, English and art songs. They have beautiful white uniforms of simple design, are very expressive in their interpretations and make a splendid appearance on the stage.”6 The fact that the Glee Club’s varied repertoire included both “negro spirituals” and “Indian songs” reflects on Hampton’s tradition of publishing spiritual and indigenous song arrangements in the early twentieth century7. By early 1934, however, Patterson was forced to resign from her position at Hampton due to administrative reorganization.8

Courtesy of Dale Patterson Family Collection, Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum, Box 8, Folder 27

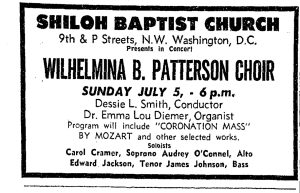

After leaving Hampton, Patterson moved back to Washington, DC where she directed the choir at Shiloh Baptist Church and served as the music director of the Burville Recreation Center Orchestra. In the 1940s, Patterson was profiled in Violet Key Smith’s newspaper column about “Interesting D.C. Women.” 9 Smith characterized Patterson as “a pleasant-faced retiring sort of person who laughs a lot.”10 In an interview with Smith, Patterson said “I don’t believe there is any greater joy in life than in training children and seeing their talents develop as much as possible.”11

Courtesy of Dale Patterson Family Collection, Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum, Box 8, Folder 27

Photos in the Dale-Patterson Family Collection at the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum demonstrate Patterson enjoyed a rich musical life in DC. In one photo captioned “Victory Sing at the Burville School with Orchestra Accompanying”, Patterson stands next to a piano with a children’s orchestra and choir. In another photo captioned, “Miss Patterson’s Ensemble Asbury Methodist Church,” Patterson plays piano on stage with a small orchestra of children. In her interview with Violet Key Smith, Patterson stated: “The thing I am most interested in right now…is setting up a music center at the home in Anacostia my brother, Fred, has given me. I want to make it a place where my musical friends, young and old, may gather in an ideal environment.”12 While no evidence exists that Patterson created her desired music center, Patterson’s multifaceted role as a music educator meant she influenced countless young musicians.

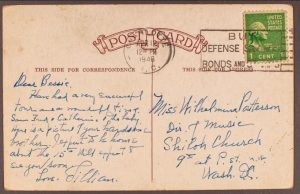

In Washington, DC, Patterson also maintained a longtime friendship with famed operatic soprano Lillian Evanti (1890-1967). Ephemera in the Dale Patterson Family Collection demonstrates Evanti sent Patterson postcards, and Patterson organized concerts for Evanti at Shiloh Baptist Church. One of those postcards is pictured below, next to its transcription.

By the time of her death in 1962, Patterson was a well-loved musical figure in Washington, DC. As a tribute to Patterson’s influence as a musician and educator, the Shiloh Baptist Church formed the Wilhelmina B. Choir in 1970 in Patterson’s honor.13 Wilhelmina B. Patterson’s musical career reveals Black female music educators shaped their communities through performance, leadership, and education.

Dear Bessie,

Had a very successful tour and a wonderful time in San Fran. California. The baby here is a picture of your handsome brother. I expect to be home about the 15th and will expect to see you soon.

Love, Lillian.

To the right is a photo of one of Evanti’s recitals. Patterson stands to the left of her in a v-necked gown with embellished shoulders.

Washington Conservatory Graduate Home Addresses from United States Census Records and City Directories

Wilhelmina B. Patterson, like many Washington Conservatory graduates who came from outside of Washington, DC, returned to her home state for work. This map visualizes where Patterson and the other Washington Conservatory graduates from 1910-1914 lived utilizing United States Census records and city directories. The map is color-coded by occupation type. Zoom in to view the graduate addresses in Washington, DC.

This map demonstrates that Washington Conservatory graduates, while primarily coming from Washington, DC, came from around the country to study. It also visualizes the communities that graduates worked and influenced after attending the conservatory.

1 “Wilhelmina Bessie Patterson,” Student Cards, Digital scan courtesy of Oberlin College Archives.

2 Year: 1900; Census Place: Washington, Washington, District of Columbia; Roll: 163; Page: 16; Enumeration District: 0113; FHL microfilm: 1240163

3 Evening Star, Washington, DC, June 17, 1911, pg. 12.

4 Howard University Moorland Spingarn Research Center, Washington Conservatory of Music Papers, Box 112-3, Folder 117.

5 James E. Gregg to Harriet Gibbs Marshall, February 28, 1921, Howard University Moorland Spingarn Research Center, Washington Conservatory of Music Papers, Box 112-5, Folder 142, Courtesy of Sarah Schmalenberger.

6 Bessie Patterson to Harriet Gibbs Marshall, April 1, 1931. Howard University Moorland Spingarn Research Center, Washington Conservatory of Music Papers, Box 112-5, Folder 142, Courtesy of Sarah Schmalenberger.

7 See Robert Nathaniel Dett, Religious Folk Songs of the Negro, (Hampton University Press, 1927). Natalie Curtis Burlin, The Indians’ Book An Offering by the American Indians of Indian Lore, Musical and Narrative, to Form a Record of the Songs and Legends of Their Race (Harper, 1907).

8 See “Ousted Music Teacher Forced to Quit Hampton Inst. Campus. President Howe Demands She Leave Jan. 29. Action Believed to Be Aftermath of Recent Protest. School Head is Away. Informant Says Negro Will Now Get Position,” New Journal and Guide, Norfolk, VA, February 3, 1934, pg. 1.

9 “Interesting D.C. Women by Violet Key Smith,” Undated newspaper clipping, Dale Patterson Family Papers, Anacostia Community Museum, M06-074, Box 4, Folder 4.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid. Patterson’s brother, Frederick Douglass Patterson (1901-88) served as the third president of the Tuskegee Institute from 1935-53 and founded the United Negro College Fund in 1944. The home Patterson refers to is likely 1395 Morris Rd, SE, Washington, DC which Patterson purchased on 7/29/1956 for $4,334.57. The full property deed is in the Dale Patterson Family Papers, Anacostia Community Museum, M06-074, Box 4, Folder 3.

13 Washington Post, Washington, DC, June 28, 1970, pg. F6

You must be logged in to post a comment.