The Unsuspecting Tour Guide

Eighth Installment

VIII. Uncharted Waters

My new companion was called Sebastien – Sebastien Vuillermoz, a distant cousin of the music critic Emile Vuillermoz. Beyond his employment as a correspondent for the London Times, there was nothing particularly remarkable about him at first glance. He was a rather tall man – a good head above me, and I was neither short nor in flat-heeled shoes – inconspicuously garbed in a plain but respectably cut suit. From his dark blond hair and hazel eyes, he could have hailed from any number of nations, while his speech, though admittedly quite eloquent when it was to be heard, was for the most part non-existent. Still, he was courteous – altogether one of those entirely decent yet inconspicuous gentleman whose merit one never appreciates until some years have passed.

It was also quite clear that, though taciturn, he knew his way around. I had thought I knew Paris, but these were districts into which I ventured but seldom. All the more surprising was the fact that this was my hometown but not his. M. Vuillermoz hailed from Grenoble, far in the south of France, nestled against the Alps.

He led me confidently down the most direct route possible, past the Eglise de la Madeleine and down the Rue Tronchet, the Rue du Havre…it was not a particularly short walk, especially in these horrible high heels. Suddenly my views on fashion were in a tailspin.

“Pardon, M. Vuillermoz – could we please slow down?” I surrendered my pride just as the Cimetière Saint-Vincent (no relation, I’m afraid) – a landmark of the Montmartre quarter1 – came into view. Obligingly, my escort stopped long enough for me to catch my breath and wiggle some life back into my toes. Why did his legs have to be so long? I wondered, wincing as I agitated one of several new blisters on my heel.

“It isn’t far,” he said, breaking a rather long, yet not uncomfortable silence. “Perhaps I should have called a taxi…?”

With his salary? Hardly.

“No, it’s perfectly alright,” I lied politely. “I just needed a moment. Shall we go on?”

He hesitated briefly, then gallantly offered me his arm, which I took gratefully. We went on.

Well into Montmartre, the scenery was very distinct from the semi-aristocratic Rue de Monceau. By now, it was late enough that Parisians and tourists alike – including that in-between category of the resident American colony – were delving into the nightlife offered by the city’s wealth of clubs, cabarets, and music halls. Down this street, and especially the Boulevards de Clichy and de Rochechouart, venues of evening entertainment quite literally lined the streets, displaying not only their attractions but also their patrons in varying stages of drunkenness. All races and classes were to be found here – black musicians or former soldiers who chose to remain in France rather than returning to America, where racial tolerance still had a long way to come2; aristocrats and the like in fine jewels and silks, eager to see how the other half lived; and the quarter’s actual residents, painters or other artists hoping to escape the worldly troubles of city-life for awhile. It was said that the Parisian had no home; he lived out his life as far from his actual lodgings as possible, because the rent rarely covered things like electricity, plumbing, or heating. All of those things could be had in the cabarets, though.3

The better clubs had bouncers posted at the entry, the bigger the better. These expelled patrons whose money could not compensate for certain other attributes, or forbade entry to those would-be guests who looked like more trouble than they were worth. As we approached Le Lapin Agile, the cabaret’s bouncer looked us over menacingly and then – to my astonishment – actually smiled.

“Sebastien Vuillermoz!” the man boomed, extending a hand which bore an odd resemblance to a knotted oak-branch. “It has been a while, my friend. I thought you had moved to London.”

“Not yet, Robbie,” my companion replied, returning the vigorous handshake. “But I come not for my own amusement. My companion-” He gestured back at me. “Is looking for a friend of hers – a young woman, American, all in pink, pixie face?”

“I remember her,” said Robbie the bouncer. “She has not left yet.”

“Can we go in?”

“Of course! No trouble, though, d’accord?”

“D’accord, mon ami.”

He let us in without further comment, and M. Vuillermoz laid a hand cautiously on my arm.

“Stay close,” he advised, eyes scanning the interior. “Things can get a bit wild in here.”

Even with that warning, I could not have anticipated what happened next. It was the sudden movement that caught my eye, bringing it immediately to a group of people sitting off to one side, in the middle of which, pretty in pink, sat Lizzie Drewry. Her expression was one of increasing alarm, eyes like two blue saucers in a pale face, as the two men on either side of her sprang up to grab each other by the collar. I yanked at my escort’s sleeve desperately. He turned, eyes narrowing.

“Oh, -”

I missed the expletive that followed, because at that moment the big, hairy fist of the man on Lizzie’s right connected solidly with the jaw-bone of the one on her left. There was a sickening crack, a woman – was it Lizzie? – screamed, then absolute chaos broke out. In the midst of the madness, which can only be likened to a riot, I saw a man in a brown beret drag Lizzie off by the arm.

“Lizzie!” I heard myself screech as I launched myself after her, only to be held back by a pair of iron-like arms.

“Let me go!” I cried, fighting the man’s grip. He whirled me about to face him, and I realized it was my escort, Sebastien Vuillermoz, who had stopped me.

“Pull yourself together, mademoiselle,” he ordered, surprisingly composed. Evidently he’d been in tight spots before. “If you go after her in this mess, you’ll be killed.”

“What do you expect me to do?” I demanded, furious.

“Robbie!” he called, turning to find the bouncer plowing through the rioters. “Who was the man in the brown beret?”

“Ask Igor Petenski!” the bouncer roared back. “That cretin was one of his. I’ve got to deal with this lot!”

“Come on,” Vuillermoz said to me, steering me expertly out a back door. Anyone who got in his way hastily got out of it, a worried look in their eyes. Had I been less rattled, I would have realized that my companion seemed to enjoy quite a fearsome reputation around these parts.

We made it out into an alleyway, where we both paused to catch our breaths.

“Are you alright?” he asked, and I nodded automatically. This night could hardly get any stranger. “Alright, then. We have to go.”

“Go where?”

“Igor Petenski. He runs a …you know, better you don’t know. I know him well enough that he’ll do me a favor.”

“Oh, great.” Just who was this man? “How, exactly, do you know so many strange individuals?”

“I’m a political correspondent for the Times. Earlier this year, I was asked to look into the possibility of France recognizing the Soviet Union as a legitimate government, and I ended up standing in the same queue as Petenski at a bakery.”

“Oh.” It seemed that fate worked in mysterious ways, indeed.

At a near run, we raced back to the Rue des Saules and from there hailed a taxi.

“It’s too far on foot,” was the only explanation I received as I was handed in.

Far too far. All the way to the Northeast corners of the city, in the quarters of the working poor. As we stepped down from the cab, I felt surrounded by the strangest mélange of languages – Italian, Russian, Flemish, and Yiddish – that ran the gamut of the immigrant groups in Paris. Mostly these had amassed wherever housing was cheap, making for a constant mixture of native and non-native Parisians4.

It was a different world. Vuillermoz exchanged a greeting in Italian with a woman sweeping her building’s doorstep; at my curious glance, he shrugged, saying,

“When I first came to the city, the only lodgings I could find were with a woman in La Villette. There’s a sizable Italian population there5.”

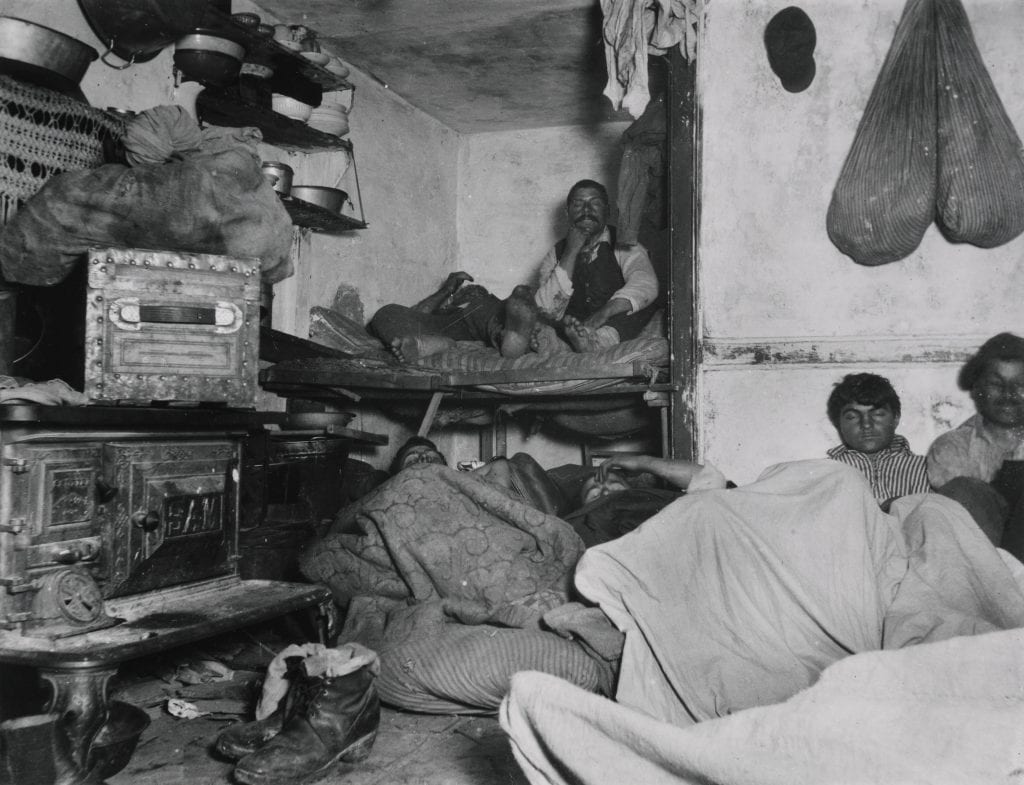

Well, that was interesting. My curiosity did not, however, cure me of the queasiness in my stomach as we stepped over suspicious puddles and unidentifiable remains. The street, though, filthy as it was, could not compare to what lay inside.

The tenement we entered was squalid, the ceiling ridiculously low and the room horribly cramped. At the table, the only furniture in the room, a man with a patch over one eye rocked a baby in his arms. He looked up as we approached.

“Sebastien Philippovich,” the man nodded a greeting toward Vuillermoz.

“Igor Dimitrovich,” the latter replied in kind. “Ça va?”

In guttural French, the Russian answered, “Oui, ça va. Qu’est-ce qui se passe?”

“I need to find someone, Igor Dimitrovich. A young woman. She left the Lapin Agile with a man in a brown beret – Robbie identified him as one of yours.”

“Which one?”

“I was hoping you might tell us. Dark hair, big as an ox, a mean right hook?”

“That describes at least ten men I know of,” remarked Igor dryly, still rocking the baby.

“He had a tattoo on the inside of his right wrist – the eye of Horus, with a serpent around it.”

“Ah.” There was recognition in that sigh, but Igor did not give up his secrets so readily. He raised his chin in my direction.

“Who’s your friend?”

“Mademoiselle de Saint-Vincent, meet Igor Dimitrovich Petenski,” Vuillermoz introduced us calmly. “Mlle de Saint-Vincent is a friend of the girl who is missing.”

“Ah. You seem uncomfortable, mademoiselle.”

Jacob Riis, “Lodgers in a Crowded Bayard Street Tenement,” Wikimedia Commons, accessed July 28, 2015.

“I have never been in such a place before,” I admitted carefully, wary of offending. The eye-patch was definitely malevolent.

“A tenement apartment, you mean? Yes, their charm is somewhat…complex, to say the least.”

“Landlords add in extra floor divisions in order to squeeze in more tenants6,” Vuillermoz explained to me, gesturing at the low ceiling. “All they care about is money.”

“Almost makes Bolshevism appealing,” chuckled Igor, without any real humor. Catching the concern that flickered across my face, he assured me, “I am no Bolshevik, mademoiselle. In Russia, my family were khulaks – a peasant class with landholding rights. The Bolsheviks have no love for us.”

“Igor left Russia after the civil war,” Vuillermoz added quietly. “Along with thousands of others.”

“Yes, I know several émigrés-”

“You know the aristocrats who still long for their victorious home-coming,” Igor noted sardonically. “Deluded old fools. Anyone can see that the French will acknowledge the Bolshevik regime before the year is out. There will be no home-coming.” Slowly, he stood, never jostling the child in his arms yet somehow bringing our attention directly to it. “Our children will soon forget their motherland. They speak French better than Russian, call themselves by French names and listen to French music7 – they will dance the cake-walk but be baffled at a mazurka.” He sighed. “We must all adapt.”

To Vuillermoz, he added, “The man you want is Sasha Mikhailovich. You will have to go to the zone to find him. The landlord evicted him last week – even I cannot defend a man who sells drugs to those who have nothing anyway.”

“Spasiba, Igor.”

Out into the street again. Weariness was taking hold, and we still had one more stop to make. Worse yet, the cab had left, and there was no way to get another in these parts.

On foot, we continued to the zone.

1. Baedeker, Karl. Paris und Umgebung. Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1923. Print.

2. Lloyd, Craig. Eugene Bullard: Black expatriate in Jazz-Age Paris. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2000. Print. 75.

3. Evenson, Norma. Paris: A century of change, 1878-1978. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979. Print. 199.

4. Blanc-Chaléard, Marie-Claude. « L’Habitat Immigre à Paris aux XIXe et XXe siècles : Mondes à part ? » Mouvement Social, 1998. 182. 29-50. JStor. Accessed June 19, 2015. 34-35.

5. Rainhorn, Judith. «Production ou reproduction? Les migrantes italiennes entre rôle maternel et intégration professionnelle : Paris (La Villette) et New York (East Harlem), années 1880-1920». Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine 2002/1 (no49-1), p. 138-155. 139.

6. Evenson, Norma. Paris: A century of change, 1878-1978. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1979. Print. 203.

7. Johnston, Robert H. “New Mecca, New Babylon”: Paris and the Russian Exiles, 1920-1945. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1988. Print.

Header:

Kertesz, Julle. “Butte Montmartre dans le brume.” Flickr, October 2007. Accessed July 28, 2015. https://www.flickr.com/photos/joyoflife/1472421624

You must be logged in to post a comment.