Mapping Black Minstrel Troupes: Identifying Patterns and Impacts

By Elsa Buck, Emma Byrd, Tess McCarty, Emma Rosen and Jack Slavik

Content Warning: This webpage includes readings, media, and discussion around topics of racism, blackface, racial violence, racial stereotypes, racial slurs, and other racist traditions. We acknowledge that this content may be difficult to consume. We encourage you to care for your safety and well-being. If you would like to see a map of Black minstrel troupe tours, click here.

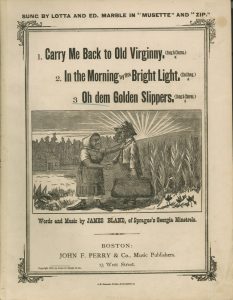

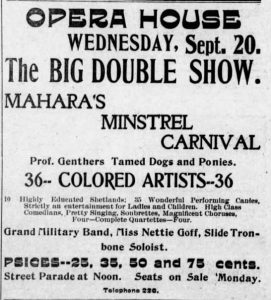

Blackface minstrelsy was once America’s most popular form of entertainment. Though easily overlooked, its echoes can be found throughout American culture today. It can be tempting to dismiss the phenomenon due to its overt racism, but to do that would also be to dismiss the impact of Black artists on American music. Those artists’ legacies are worth preserving, and digital maps are one way to begin that work.

The minstrel show is one of the clearest examples of racism embodied in American popular culture, and for this reason it is often little discussed today, except perhaps as some sort of horrific ghost of our past. But minstrelsy might better be considered the ghost of our present. Extremely persistent in US American culture in general, but especially the entertainment industry, one need not go back to the 19th century to see minstrel tropes in the media (Johnson). Minstrelsy was not, however, as one-dimensional as we are often led to believe. While it was inarguably racist, the constant interplay of race, class, and gender makes understanding and interpreting minstrelsy all the more challenging. At the beginning of our research, we were surprised to learn that Black entertainers also participated in blackface minstrelsy before and after the Civil War, with some making extremely successful careers out of it. Their achievements and legacies further complicate our contemporary understanding of minstrelsy.

“The problem with approaching history in America is that too many people measure things by distance and not by impact.”

-Hanif Abdurraqib, Little Devil in America (80), 2021

“Ultimately, the measure of its cultural power in this period is the claim the minstrel show made, against all the odds, on the idea of a national culture.”

-Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (91), 1993

You must be logged in to post a comment.