Raw Data Tables

Research Methods

Scholarship and Databases

Our work is substantially stronger thanks to several scholars with whom we have personally corresponded. We are indebted to Dr. Sandra Graham of Babson College and Dr. Carol Oja of Harvard University (St. Olaf Class of 1974) for their time, advice, and willingness to let us bounce ideas off of them. Both Graham and Oja have studied Black music for years, and offered invaluable insight into the field. Dr. Louis Epstein, our professor, has helped us with the research process and prepared us as critical thinkers to undertake such a massive project.

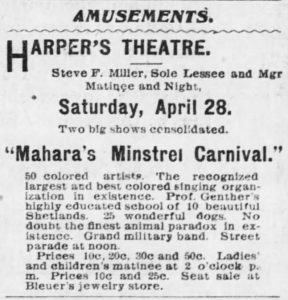

In addition to scholars with whom we have personally corresponded, we have relied heavily on the scholarship of experts in the field. Eileen Southern’s The Music of Black Americans served as valuable background information about many of the big players in the industry, and led us to the important autobiographies of WC Handy and Tom Fletcher, who were performers in the minstrelsy industry around the turn of the 20th century. Her book also encouraged us to investigate differences in touring patterns and ticket pricings between white-owned Black troupes and Black-owned Black troupes. Abbott and Seroff’s Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889-1895 helped us better understand the relationship between troupes, many of which changed ownership over the years. This book also provided a wealth of primary source resources, and frequently discusses the demographics of those in attendance at Black minstrel shows, which piqued our interest and led us to study the demographics of heavily toured areas using historical census data.

To populate our maps, and to gain insight into the wide variety opinions about Black minstrelsy at the time, we relied on historical newspaper databases, primarily Readex’s African American Newspapers and newspapers.com. We recognize the limitations of using only a select few databases, but also the opportunities we have as researchers in the 21st century with extensive access to countless primary sources. We encourage future researchers to further diversify their databases to avoid selection bias, an issue we ran into by only using a few databases. However, to our knowledge, extensive mapping research of this kind has never been done on this subject, so we have a unique opportunity to nuance existing scholarship and provide a starting point for other researchers interested in continuing this work.

Process

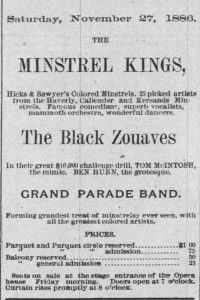

Part of what guided the direction of our research were the challenges we faced in gathering primary source data. The history of minstrel troupe ownership is convoluted. Many troupes changed ownership and therefore changed their name while others kept the same name under different ownership. For example, the Georgia Minstrels were originally owned by Charles Hicks, a Black man, but Hicks eventually sold his ownership stake to George Callender because Hicks was unable to make bookings in theaters as a Black man. Callender later sold the troupe to J.H. Haverly, who sold it to the Frohman brothers. Almost every troupe we studied changed ownership at least once throughout its history, and many troupes changed from Black to white ownership. This fact guided our decision to focus on both Black- and white-owned troupes: we were interested in whether tour routes would be different, given that Black owners faced challenges getting bookings.

Unfortunately, the number of search hits varied greatly for each minstrel troupe across our databases. It was much more difficult to find data for Black-owned troupes, which often operated for smaller spans of years, and ticket prices were especially difficult to find. Whether this is due to underreporting of their performances or if they truly had fewer performances than white-owened minstrel troupes we do not know; answering that question falls beyond the scope of this research. Knowing of the disparity, however, drove us to continue to seek out information from Black-owned minstrel troupes. Data varied by troupe as well; McCabe and Young’s Minstrels had comparatively more results than Hicks and Sawyer’s, for example. Our initial idea was to narrow the scope of our research to a specific decade, even a few specific years, but due to the lack of significant amounts of data, and our desire to include Black-owned troupes, we decided to include data points from a broad chronological timespan: 1871 through 1939.

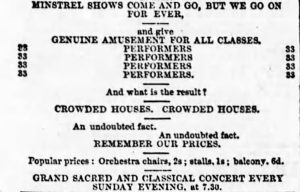

Some challenges in our research were the result of using digitized newspapers as our primary medium. As might be expected from 150+ year old sources, some newspapers were just plain difficult to read. And although digitized newspaper collections are a phenomenal development and great resource for us, the system is not perfect. Sometimes our search would turn up unrelated phrases, sometimes it would find a phrase match when there really wasn’t one at all, and oftentimes the database would miss important phrases elsewhere in the paper. In fact, one of our very first insights was to put the name of our troupe in quotes in the search bar followed by ‘seats’ or ‘tickets’ or ‘prices’ outside of the quotes, which usually turned up useful performance data. Other linguistic challenges at the primary source level include vague phrases such as “Popular prices” (below, left) or “Admission as normal.”

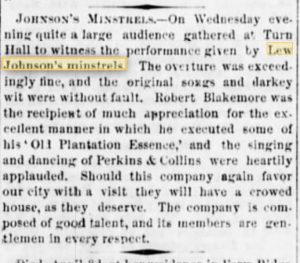

Early on, we discovered that while our interest in ticket prices was driven by a compelling research question, it was also constraining our ability to locate evidence of Black minstrel troupe performances. This realization contributed to our decision to create a new dataset of performances without clear ticket prices. By doing this, we were able to make maps that better represent Black minstrel performances of the late 19th century and early 20th century. We also found that minstrel troupes were commonly mentioned in newspaper reviews or opinion panels, which often provided more interesting context than the advertisements with ticket prices (above, left).

We have intentionally shared our data with the public in hopes that our research and data can be build on and used by others. Click Here to access our download-friendly spreadsheet.