“My greatest claim to fame is that I discovered Bricktop before Cole Porter [did].”

-F. Scott Fitzgerald

Bricktop in 1925 at Le Grand Duc. http://riverwalkjazz.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Bricktops-LeGrandDu25-139×300.jpg

Ada Beatrice Queen Victoria Louise Virginia Smith (known more commonly as “Bricktop” due to her red hair) was an American singer, dancer, and jazz-club proprietor who became a cornerstone of the African-American jazz community in Paris. She began performing at the age of 16, and she quickly rose to prominence in the vaudeville circuits of Chicago and New York City. On May 11, 1924, she arrived in Paris to replace Florence Jones as a performer at Le Grand Duc in Montmartre. (Shocked and disappointed by the cabaret’s tiny size, Bricktop burst into tears upon arrival—only to be consoled by a helpful busboy by the name of Langston Hughes).1 Word of her talent and charm spread quickly, however, and in at least one 1925 newspaper she was erroneously reported to be the manager of Le Grand Duc, rather than simply a performer (much to the annoyance of her former employer, Eugene Bullard).2 By 1926, she had opened her own club, called the Music Box (though it was often referred to simply as Bricktop’s). Later, in 1929, Chez Bricktop moved down the road to 66 rue Pigalle. Bricktop herself played the various roles of performer, hostess, accountant, manager, and bouncer; her business was synonymous with her personality.

Bricktop’s established itself as a central hub for the black jazz community in Montmartre. African-American expatriate musicians like Sidney Bechet would play their sets at surrounding clubs and dancings, and then turn to Bricktop’s later in the evening. Establishments like this, in which African-American proprietors would hire African-American musicians, strengthened the small but significant black community in the area and helped jazz rise to cultural prominence in Montmartre. 2 Bricktop’s clientele largely consisted of wealthy white patrons, resulting in a space shared between black and white American expatriates, in which racial divides were less strict than in the United States.4 (This is not to say that the Paris jazz scene was free from racism- far from it- but that is a topic for another post.)

Bricktop (2nd from left) and Mabel Mercer (2nd from right) with guests at Chez Bricktop in 1932. http://riverwalkjazz.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Bricktops-and-Friends1-300×173.jpg

Bricktop’s was known for its friendly, highly fashionable atmosphere. Bricktop kept up with trends in American music through her mother, who smuggled Fletcher Henderson and Duke Ellington phonograph records through customs when she came to visit, in order avoid expensive French taxes.5 Well-known writers of the “Lost Generation,” such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, were regulars at the club. Cole Porter enlisted her to teach him the Charleston, and the two developed an extensive social relationship. 6 On one striking occasion, Bricktop threw John Steinbeck out of her bar for being “ungentlemanly.” (He apologized by sending her a taxi filled with roses.)7

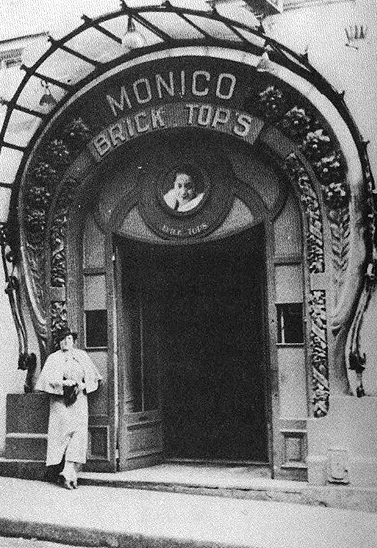

The main entrance to Bricktop’s, at 66 rue Pigalle. Photo by Carl Van Vechten. http://riverwalkjazz.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Brick-Tops.jpg

Bricktop’s cabarets in Paris no longer exist, but the writings of her friends and club patrons offer us a glimpse into the atmosphere of the bar, and into the dynamic personality of its owner. The American writer Robert McAlmon leaves us with the following portrait:

“When…I arrived there the place was crowded. One drunken Frenchman wanted to get away without paying his bill. At another table a French actress in her cups was giving her boyfriend hell and throwing champagne into his face. In the back room several Negroes were having an argument. Brick sat at the cashier’s desk keeping things in order. With a wisecrack she halted the actress in her temper, cajolingly made the Frenchman pay his bill, and all the while she was adding up accounts, calling out to the orchestra to play this or that requested number…She began to sing “Love for Sale,” while still adding up accounts. Halfway through the song there was a commotion in the back room where the argument was taking place, which meant that the colored boys had now come to blows. Brick skipped down from her stool, glided across the room, still singing. She jerked aside the curtain and stopped singing long enough to say, “Hey you guys, get out in the street if you want to fight. This ain’t that kind of joint!” Then she continued the song, having missing [sic] but two phrases, and was at her desk again adding accounts.”8

1 Sharpley-Whiting, T. Denean. Bricktop’s Paris. (Albany: State University of Neew York Press, 2015), 28.

2 Sharpley-Whiting, 24.

3 Jackson, Jeffrey H. Making Jazz French: Music and Modern Life in Interwar Paris. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 56.

4 Jackson, 67.

5 Jackson, 68.

6 Sharpley-Whiting, 33.

7 Krebs, Albin. “Bricktop, Cabaret Queen in Paris and Rome, Dead.” The New York Times, February 1, 1989.

8 McAlmon, Robert. Being Geniuses Together: A Binocular View of Paris in the ’20s. Revised by Kay Boyle. (New York: Doubleday, 1968), 316-317.

Wonderful post! You’ll have to link to this in your map of Parisian jazz within the marker for Bricktop’s. In fact, I can imagine blog posts on a number of jazz establishments that users can access through the map. I particularly appreciate the blend of colorful anecdote and hard fact that you present here, as well as your use of primary source recollections. For another one of those, you might go to Langston Hughes’s autobiography – I believe he was in the city in 1924 (there’s a blog post about his first night in the city somewhere on this website) and his would be a particularly authoritative first person account of Bricktop. For the map, you might also link to some New York Times or French newspaper articles about Bricktop from the 20s, assuming you can find some. The research never ends, but with a start as good as this one, it would be a shame not to follow up.