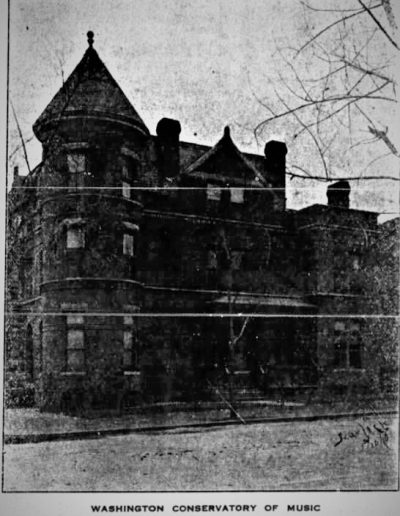

What Was the Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression?

Founded in 1903 by Harriet Gibbs Marshall, the Washington Conservatory of Music was the first private institution of higher education created by and for Black musicians. Thousands of students received lessons and hundreds received degrees while studying at its multiple locations in the Washington, DC, metro area between 1903 and 1960, when it closed. To its students, faculty, administrators, and many others around the country, the Washington Conservatory was a beacon of progress and achievement, steeped in the politics of Reconstruction-era racial uplift even as it wrestled with challenges in an era of deepening segregation and discrimination.

The Washington Conservatory of Music offered a comprehensive music education. When it opened in 1903, its catalog included seven courses of study: String ensemble, music history, musical biography, harmony, public school performance, class piano, and applied instruction on organ, piano, voice, and strings.1 At the time, this was a broader selection of classes offered than Howard University, only blocks away and with its own respected music program.2 In later years, the conservatory added piano tuning, organ building, and piano tuning courses.3 Originally operating out of True Reformer’s Hall, within a year of its opening the school moved to 902 T St NW, where it remained until it closed.4 With this move also came a new department, the School of Expression, where students could study elocution and oratory skills.5

Some of the Washington Conservatory’s notable faculty members include Clarence Cameron White, who taught violin from 1903 to 1907 and who graduated from Oberlin College alongside Harriet Gibbs Marshall. He served as the head of the strings department and later became the president of the National Association of Negro Musicians.6 Emma Azalia Hackley, a renowned vocalist, also taught at the conservatory from 1903 to 1904.7

Like other music programs at HBCUs that are better known today, including those at Fisk University, Hampton Institute, and Tuskegee Institute, the Washington Conservatory trained its students in the Western European art music tradition while also fostering performance and preservation of Afro-diasporic classical music. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was a frequent name on Washington Conservatory programs, and many students performed instrumental and vocal arrangements of spirituals alongside canonic repertory.8

Unlike competitor programs at HBCUs, however, the Washington Conservatory boasted an all-Black roster of teachers and administrators. This distinction mattered quite a bit: as Jarvis Givens and others have shown, the presence of white administrators and teachers often constrained Black education. Conversely, the pedagogical and historical expertise of Black administrators and teachers often meant a higher bar for educational attainment and a truer representation of Black contributions to American culture and history.9 Today, predominantly white music programs such as Oberlin, the New England Conservatory, Curtis, and Juilliard celebrate their respective histories of inclusion because they graduated a handful of exceptional Black classical musicians over many, many decades. But the Washington Conservatory – which has faded from the public consciousness – graduated hundreds of Black classical musicians, motivated not by a politics of inclusion or tokenism, but by the firm conviction in the utter normalcy of Black classical musicianship.

The people who attended the Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression came from around the country, and went on to pursue a variety of rich careers in and outside of music. Many became educators and performers around the country. Henry Lee Grant, for example graduated from the conservatory’s Artists Course in 1910 with degrees in piano and music theory.10 He became a teacher at Dunbar High School,11 the president and founder of the National Association of Negro Musicians,12 and a composition teacher for Duke Ellington.13 In 1911, Wilhelmina B. Patterson also graduated with degrees in piano and music theory from the Artists Course. She went on to become a faculty member at multiple HBCUs, including Prairieview A & M and Hampton University, where she served as a director of music. After leaving Hampton, she moved back to Washington, DC and directed the choir at the Shiloh Baptist Church. She also served as music director at Burville Recreation Center. After graduating from the Teachers Course in 1912, Grace G. Brown moved to Greensboro, North Carolina, where she taught first grade at Jacksonville and David Jones schools, all the while teaching private piano lessons in her home.14

Graduates of the Washington Conservatory 1910-14

Our project traces the lives and impacts of Washington Conservatory graduates from the classes of 1910 through 1914. Because our work unfolded over a ten week time frame, we limited ourselves to studying graduates of the first five classes only. These were crucial years for the conservatory, as this was when the school was becoming established and set the tone for decades to come. Additionally, because these are the earliest classes, we can better assess the effects these graduates have had on their communities over time. The stories of the Washington Conservatory of Music’s classes of 1910 through 1914 offers a new perspective of Black American musical life. This work is necessarily incomplete, and could be continued, in part, by resuming tracing the lives of graduates from 1915 and beyond.

Our work is founded on the scholarship done by Dr. Doris McGinty, who performed groundbreaking research on the conservatory and Harriet Gibbs Marshall. Dr. McGinty was a musicologist and professor at Howard University from 1947 to 1991. Her articles and chapters on Black musical life in Washington, DC, opened up a new field of research at a time when many white musicologists remained skeptical of the value of studying Black music history. Dr. McGinty became a mentor for another scholar whose work informs our own: Dr. Sarah Schmalenberger, a musicologist and professor at the University of St. Thomas, wrote her dissertation and a series of articles on Harriet Gibbs Marshall and the Washington Conservatory. She was also generous enough to meet with us and share some of her unpublished research. We are deeply grateful to Dr. McGinty, whom we wish we had met, and to Dr. Schmalenberger, who helped this project soar.

Walking Map of Washington, DC Points of Interest

To better understand the neighborhood surrounding the Conservatory, including where graduates lived, learned, and worked, visit our walking map below. You can feasibly walk this route in under one hour, visiting the Washington Conservatory of Music building and other homes, schools, and churches in the area. Scroll down to view the walking map route, and continue scrolling within the map to view the points of interest.

1 Sarah Schmalenberger, The Washington Conservatory of Music and African-American Musical Experience, 1903-1941, pg 45.

2 Doris McGinty, “The Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression,” The Black Perspective in Music 7 no. 1 (1979), 62.

3 Schmalenberger, 46.

4 McGinty, 61.

5 Schmalenberger, 49.

6 Eileen Southern, The Music of Black Americans, 272.

7 Schmalenberger, 47.

8 Howard University Moorland Spingarn Research Center, Washington Conservatory of Music Papers, Box 112-56, Folders 4, 12, and 17; and Schmalenberger 224- 263.

9 See Jarvis Givens, Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021.

10 First Commencement Program, June 3, 1910. Washington Conservatory of Music Papers, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Box 112-52, Folder 21.

11 Dunbar High School 1925 Yearbook, Courtesy of Sumner School Museum and Archives, Washington, DC.

12 “Artists and NANM First Draft (June 1996),” Doris McGinty Papers, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Box 45-16, Folder 38, pg. 46.

13 Mark Tucker, “The Early Years of Edward Kennedy ‘Duke’ Ellington, 1899-1927,” PhD Diss, University of Michigan, 1986, 133.

14 “The Obituary” in A Service of Witness To The Resurrection Celebrating the Life Of “Princess” Grace Brown program, Greensboro, NC, August 26, 1993, 2. Accessed courtesy of Phylicia Fauntleroy Bowman.