Sources and research methodology

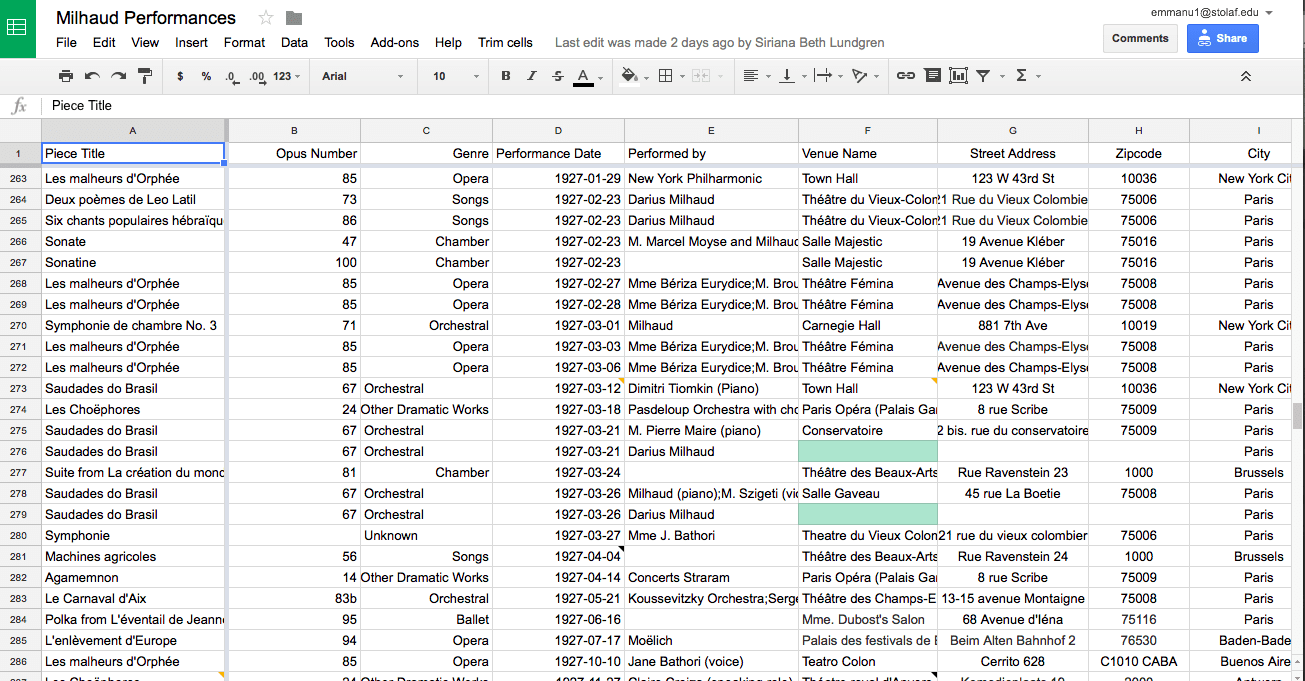

Over the course of two months, the 2017 Musical Geography team compiled a database of more than 500 performances of Milhaud’s music between 1922 and 1933.

In order to find all this information, we sifted through a variety of primary, secondary, and tertiary sources, some in English but most in French and German.

As you scroll down this page, you can find out more about the types of sources that we used as well as the methodologies that we adopted.

Which sources did we use?

We predominantly drew on primary sources including newspapers, periodicals, published and unpublished correspondence, and concert programs as well as Darius Milhaud’s autobiographical writing. Many of these sources have been digitized by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and are available via gallica.bnf.fr. In contrast, some of the correspondence and autobiographical writings have been published.

We accessed one important source – Le Guide du Concert, a weekly publication that documented every public performance in Paris between 1910 and 1952 – on microfilm. And Professor Epstein shared his personal photographs of hundreds of Milhaud’s unpublished letters, a catalogue of which you can find here.

Below is a selection of primary sources that we used in each category.

| Newspapers | Music Periodicals | Correspondence | Online Archives | Autobiographical Writing |

| Le petit parisien

New York Times London Times Paris-Soir Comoedia |

Le Menestrel

Le courrier musical Le guide du concert The Chesterian Anbruch Melos |

Milhaud’s unpublished correspondences

Correspondences Milhaud-Hoppenot Francis Poulenc’s correspondence Paul Collaer’s correspondence |

New York Philharmonic

Boston Symphony Orchestra Vladimir Golschmann Roger Desormiere |

Milhaud’s My Happy Life

Milhaud’s Notes sans musique |

Additionally, one of our team members went to Paris to explore various musical locations and archives, including the Département de la Musique, the Département des Arts du Spectacle, and the Musée-Bibliothèque de l’Opéra within the Bibliothèque Nationale de France; the Médiathèque Musicale Mahler; and the Archives Nationales. The aim of this trip was twofold: to search for Milhaud’s private performances in Paris, as these tend not to be referenced in digitized newspapers and periodicals or in Le Guide du Concert, which St. Olaf owns on microfilm. On the other side, this trip also aimed at collecting more information on Milhaud’s performances in France and Europe, which proved to be useful mainly for the performances that we were still missing quite a lot of information on.

How did we make use of these sources ?

Each of these sources served an incredibly role , whether in collecting information, filling in the gaps, as well as confirming our previous findings.

- Letters and correspondences

Letters and correspondences often times contained information about performances that were possibly about to take place or that previously took place. However, most of the references to these performances were either too vague or not necessarily accurate.

They only allowed us to find general information about Milhaud’s performances – a city or a piece name – but skimped on other details (such as the specific venues where these performances took place, the exact dates when they took place, etc. )

They only allowed us to find general information about Milhaud’s performances – a city or a piece name – but skimped on other details (such as the specific venues where these performances took place, the exact dates when they took place, etc. )

Other times, the information provided in these letters tended to be inaccurate as sometimes the performances that were mentioned never really took place or simply occurred at different times.

Luckily, the following sources helped us identify more details about Milhaud’s performances as well as increase the reliability of our findings.

- Newspapers and music periodicals

Through newspapers and periodicals, we were able to strengthen the quality and certainty of our findings. In fact, because newspapers and periodicals in general report on events that already happened, they tend to be more reliable. For instance, when we came across performances that we had previously identified, newspapers and music periodicals helped us confirm that these performances indeed took place.

Moreover, through these sources, we were also able to find additional information about Milhaud’s performances such as the specific venues and/or addresses where they took place, the names of performers, and more details about the pieces that were performed.

Moreover, through these sources, we were also able to find additional information about Milhaud’s performances such as the specific venues and/or addresses where they took place, the names of performers, and more details about the pieces that were performed.

For performances that took place in France, we primarily used the French national library’s digital portal, Gallica, where we found many details about performances and events that took place in Paris, the French provinces, and Brussels, as reported on by newspapers and periodicals. Using a microfilm reader, we also scrolled through Le Guide du Concert , which lists all the musical performances that took place in Paris day by day, during the years that we were looking at. With a date and the knowledge a performance took place in Paris, we could use Le Guide du concert to confirm details like venue and which works were being performed. Finally, because Milhaud was also very popular in Germany, Austria, and The Netherlands, we also used archive.org to access German-language periodicals like Melos or Anbruch, which reported on performances of Milhaud’s music in Central Europe and elsewhere.

- Autobiographies

Milhaud’s autobiographies, Notes sans musique and My Happy Life, mainly helped us identify new performances as well as places where he may have traveled during his musical career. However, autobiographies were somewhat limited as sources; often they provided little detail about the performances.

Milhaud’s autobiographies, Notes sans musique and My Happy Life, mainly helped us identify new performances as well as places where he may have traveled during his musical career. However, autobiographies were somewhat limited as sources; often they provided little detail about the performances.

For example, a performance could be mentioned without an exact date or an exact location. This consequently would always bring us back to newspapers and periodicals, in order to be certain and more precise about the information that we collected.

- Concert programs

Digitized concert programs helped us find missing information and a few new performances. For performances that took place in the US, we looked mainly at the Boston Orchestra archives as well as the New York Philharmonic archives, as these tended to be the orchestras that performed Milhaud’s music. Similarly, the Vladimir Golschmann online archive, which provided for the most part full details about Golschmann’s concerts, helped us identify instances when Golschmann conducted Milhaud’s works.

- Paris research

Sending a student to Paris made it possible to access resources that haven’t been digitized and aren’t available in American libraries. One of our team members, Elizabeth, went on a two-week trip to Paris, digging intensively through collections of press clippings, bureaucratic documents, and unpublished letters.

There, she was able not only to confirm a lot of our previous findings but also to add up new ones, through very precious and reliable sources.

For more on her trip and the various archives she visited, read her blog post about the experience.

You must be logged in to post a comment.