Mapping Slave Songs of the United States

Introduction

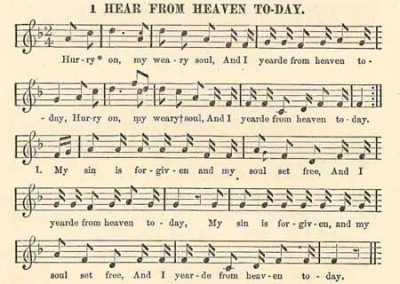

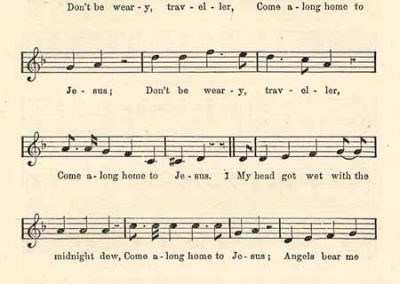

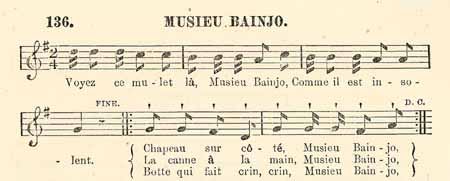

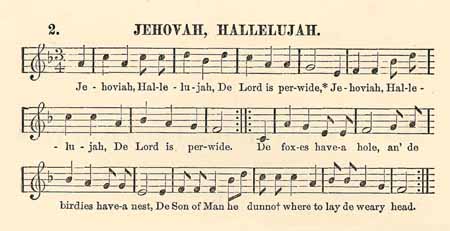

Slave songs – spirituals, Old Plantation songs, songs of the contraband – form an important if often difficult to quantify or categorize phenomenon of American music history. Around the time of the Civil War (1861-1865), there was a burgeoning of interest in documenting the songs of the black South. Abolitionists, in particular, fueled this interest, and had the opportunity to take note of the slave songs throughout the war while they performed military, government, or charity services near plantations captured by Union troops. Slave Songs of the United States represents what was, at the time, one of the most comprehensive collecting efforts, drawing on earlier collections published by Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mr. H. G. Spaulding, among others. The editors, William Francis Allen, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim Garrison, belonged to a close social circle of mainly white abolitionists and academics on the East Coast. Their collection published 136 separate songs collected mainly from the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina, where each of them had spent time during the war. They drew additional songs and variations from the contributions of friends, acquaintances, and others who responded to the advertisement placed in his newspaper, The Nation, by Lucy McKim Garrison’s husband, Wendell Phillips Garrison. The editors then placed the words and tunes of the songs they heard slaves and freedmen singing into standard, Western-scale musical notation while making note of the context in which each piece was found.

Allen, Ware, and McKim Garrison themselves were less concerned with the place or geographic situation of their carefully documented musical selections than with making the beauty of the slave songs widely known. Mapping the Slave Songs of the United States sheds new light on how scholars have historically conducted research on the African American spiritual. This series of maps argues for greater attention to the history of this research. The argument builds on three claims: first, that the mapping of the mid-nineteenth century collections of ‘slave songs’ is useful in its own right as a visual representation of the spread of common spirituals, many of which remain well-known in the present day; second, that an avenue of proposed further research is the comparison of the geographic density of the collecting data against the known whereabouts of the credited contributors for the purpose of evaluating this genre of source’s limitations toward understanding the development and spread of the African American spiritual; and finally: that this development and spread is better understood in comparison to known movements of the people to whom little credit is given within the source material, but who are responsible for the creation and earliest dissimulation of the ‘slave songs’ within this and other collections – the slaves and freedmen of the United States.

The Maps

This first map provides a general idea of the trends discovered in both the Slave Songs of the United States data set and the supplemental data set of sites from the Underground Railroad. The widget on the right corresponds to the Slave Songs data, while the legend highlights the color of the Underground Railroad points. Toggling the widget will allow you to sort the Slave Songs titles by the regions established by the editors of the collection: Southeastern Slave States, Northern Seaboard Slave States, Inland Slave States, and Gulf States/Miscellaneous.

The following map isolates the data points for each song entry in the Slave Songs of the United States. Points on the map in different colors belong to the four regions assigned by the editors – note the outlier in New York, which may seem surprising. Clicking on each point also reveals each song’s title, precise location of origin according to the collectors, name of contributor, and the lyrics provided by the editors for the song. An asterisk after a song title indicates that the song is a variation or has been cited in an additional location.

A heat map of the same data represented in a point-by-point mapping of the Slave Songs of the United States highlights the density of data points especially along the coast of the Southeastern Slave States. Allen, Ware, and McKim Garrison spent most of their time in the area of Port Royal, South Carolina, in the Sea Islands, which may be one reason for the uneven distribution. By contrast, the songs collected from further inland were contributed by fellow northerners who spent little to no actual time in the region, or by Union veterans.

This final map includes the data points from the National Park Service on sites from the Underground Railroad, styled as a heat map. Scattered between them are the discrete points of songs from the Slave Songs of the United States. By comparing the density of sites attributed to the Underground Railroad against the cited provenience of any of the songs in the collection, the map considers the relationship between the spread of this music and the movement of slaves using the Underground Railroad system.

The Music

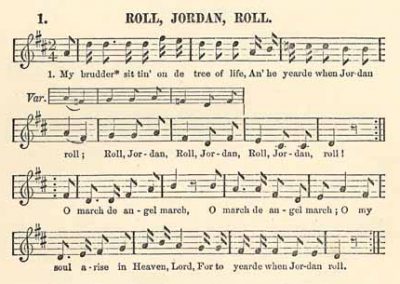

An important part of the Musical Geography project has always been finding a way to listen in on the past. Because of the difficulties in recreating the sounds of the songs that inspired Allen, Ware, and McKim Garrison to compile their book, the selection of videos you’ll find below is a random smattering of the many adaptations of these songs. They range from reinterpretations of the spiritual genre within movies on African-American history to the hymnal versions found in many Protestant and non-denominational churches. None of them can claim to be entirely historically accurate; some are closer to the versions published in Slave Songs of the United States, for which the musical notation has been provided. Hopefully, their diversity will inspire further contemplation, conversation, and investigation into what this genre represents and how it should be further represented.

What’s the takeaway?

Always a good question. On the one hand, the above maps should incite a certain interest in the subject as well as the item of the source, Slave Songs of the United States. Further reflection as well as a digestion of the available sources and recommendations toward pointed research springing off the map is to be found within the adjoining research blog. Browse the links below for information on the mapping process and the decisions taken to direct this research project.

More to the point, this map should lead to refinement of the data set and toward the mapping of other documents within this genre. The collections of African-American slave songs are numerous, but their biases must be thoroughly evaluated and the geographical inadequacies accounted. As exploration of the maps should demonstrate, the compilers of such collections were a small circle of passionate, interested individuals whose main method of data mining was observation in a single, or set of environments. A full understanding of this field would require a deep mapping technique with the addition of several dozens of sources. If this particular undertaking fulfills any one ambition, it is to convey to its audience that it merely taps the tip of the iceberg, and that further research into the applications of mapping the history of the African-American spiritual and its collection/dissemination is warranted.