About This Project

Content Warning: This webpage includes readings, media, and discussion around topics of racism, blackface, racial violence, racial stereotypes, racial slurs, and other racist traditions. We acknowledge that this content may be difficult. We encourage you to care for your safety and well-being. If you would like to see a map of Black minstrel troupe tours, click here.

Blackface minstrelsy was once America’s most popular form of entertainment. Though easily overlooked, its echoes can be found throughout American culture today. It can be tempting to dismiss the phenomenon due to its overt racism, but to do that would also be to dismiss the impact of Black performers on American music. Those artists’ legacies are worth preserving, and digital maps are one way to begin that work.

“The reason I am writing this book is to put on record the names of unsung great pioneers who blazed trails for those who followed. A great many of those I am writing about were born in slavery. Others were born of free parents who had made their escape, or were bought and carried into states which had discarded slavery. The originality of these people, who had very little or no education at all, was something to behold. Their original songs, dances and patter, created on the plantations, are still being used on the live stage, in moving pictures, radio and television productions of today.” – Tom Fletcher, 100 Years of the Negro Showbusiness (39)

Clipping from newspapers.com

The minstrel show is one of the clearest examples of racism embodied in American popular culture, and for this reason it is often little discussed today, except perhaps as some sort of horrific ghost of our past. But minstrelsy might better be considered the ghost of our present. Extremely persistent in US American culture in general, but especially the entertainment industry, one need not go back to the 19th century to see minstrel tropes in the media (Johnson). Minstrelsy was not, however, as one-dimensional as we are often led to believe. While it was inarguably racist, the constant interplay of race, class, and gender makes understanding and interpreting minstrelsy all the more challenging. At the beginning of our research, we were surprised to learn that Black entertainers also participated in blackface minstrelsy before and after the Civil War, with some making extremely successful careers out of it. Their achievements and legacies further complicate our contemporary understanding of minstrelsy.

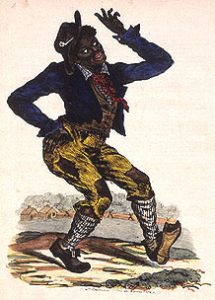

A basic history of American minstrelsy is necessary to identify the persistence of minstrelsy’s legacies in the present day. Central to the minstrel show was the use of blackface, a practice that was often achieved using burnt cork, but also through other methods, like greasepaint (Post). But blackface was not an invention of the American minstrel show. It dates back to medieval England and had a performance tradition in Shakespearean theatre long before colonizers first arrived in the Americas. Even in England, blackface was often used to denote sin and evil (Thompson), so it takes no great imagination to envision the adoption of the practice on the American stage. T.D. Rice, a white man often considered the “Father of Minstrelsy”, began solo blackface performances in the 1830s and was met with great enthusiasm. Rice’s “Jim Crow” character later gained infamy as the namesake of racial segregation laws in the post-Civil War South (Winans). Early, pre-war minstrelsy was performed almost entirely by white men and for male audiences. There were, of course, notable exceptions, such as the Luca family, a group of free Black performers who travelled throughout the Midwest and West (Fletcher), and William Henry Lane, better known as “Master Juba”, a dancer and musician who performed with white minstrel troupes in the 1840s (Abdurraqib).

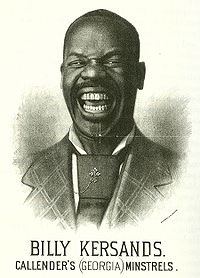

After the Civil War, minstrelsy changed in several important ways. Unsurprisingly, it became much more popular as a result of increased racial tensions. Audience composition changed, since Black people could now attend shows more readily. The basic structure of the shows solidified and they became more family oriented, with many advertisements noting that the shows were good for women and children (above). Most importantly, Black performers and entertainers entered the business in large numbers. While many of these performers and troupes are well studied, particularly from the later days of minstrelsy, little is known about the details of their tours and the demographic of their audiences; this is the focus of our research. But before we delve into these details there are a few important aspects unique to Black minstrelsy that are important to contextualize.

The first is the inherent tension faced by performers: they constantly juggled expectations of adherence to white stereotypes with their own agency to reclaim such a racist form of entertainment. A good example of this tension is the famous composer and songwriter James Bland, who was one of the most successful minstrel composers of his day. Although Bland did write some songs that conformed to racist stereotypes, and many of these are his most famous ones today, in reality Bland wrote on a variety of topics, including antislavery songs (Hullfish). To deny this aspect of minstrelsy is to deny the agency of the Black performers and composers, who, in the face of violence, oppression, and white expectations, still managed to take back some control over their representation. Even the most defining and demeaning aspects of minstrelsy could be harnessed as a social critique – including blackface. The famous vaudeville duo Williams and Walker did just that, using blackface to confront audience’s expectations about what Blackness really looked like (Post).

Bert Williams and George Walker image from the Yale Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Although minstrelsy was a unique (and often the only) employment opportunity for Black entertainers and musicians, travelling throughout post-Civil War America was far from easy. Rampant white supremacy and racial violence was a fact of life. Bigger troupes slept in special cars that they toured in, though these were often mobbed. W.C. Handy began his career as a member of Mahara’s minstrels; in his autobiography he recounts his memories of such mobs and of the lynching of a band member (43). Smaller troupes were often forced to sleep in the theaters in which they performed, which were not heated, nor particularly comfortable. But this was their only option. Many towns had very small or nonexistent Black populations, and the Black entertainers were hardly welcome there after the show was over. Author, historian, and former minstrel troupe performer Tom Fletcher remembers, “Usually they had signs prominently displayed which read ‘[offensive slur], Read and Run.’ Sometimes it would be added ‘and if you can’t read, run anyhow’”(57). Unlike white minstrels, who could simply take off their makeup at the end of the day, Black minstrels faced violence and persecution around the clock. This stark reality is particularly uncomfortable when you consider the extreme popularity of these Black troupes, who were seen by whites as more “authentic” or “genuine” and praised unendingly in the white press. As author Hanif Abdurraqib powerfully summarizes, “Consume what you can never become, and then kill it before it continues to remind you.”

Black minstrel shows did not perform exclusively for white audiences, however. Theaters often had a section designated for “colored people,” and especially popular troupes like Richard and Pringle’s Colored Minstrels sometimes had to turn away Black audience members. A show in Memphis was purportedly attended by over 4000 Black people compared to just 1000 white people (Seroff). Some Black newspapers wrote very positively about Black troupes. A writer for the Cleveland Gazette in 1886 gushed, “We wish the boys all the success in the world…they used to rehearse above this office…Oh! Good luck to you boys, or rather ‘Georgia’s.’” Of course, not all Black people were amused. Black Americans were not, and never have been, a monolithic group, and a wide variety of opinions about minstrelsy existed at the time. “It seems to me a pity that the young colored people patronize the minstrel shows that merely burlesque sacred songs of the old days,” complained a writer for the Savannah Tribune in 1914. In a similar vein, a writer for Sentinel in 1881 asserted, “It is a pity that the colored people cannot find something better in which to employ their talents. If the play-going public would occasionally allow these troupes to play to empty benches…it would go a long way towards ridding us of the nuisance.” When considering this diversity of opinions, it is important to keep in mind some of the other tensions that existed regarding minstrelsy, especially class bias. “It goes without saying,” observes Handy in his autobiography, “that minstrels were a disreputable lot in the eyes of a large section of upper-crust Negroes.” (33)

The complexity of the Black minstrel show is difficult to fully capture, but we hope that throughout this short introduction we have provided resources and perspectives that help contextualize and humanize the people whose lives and work our research relies on. As we discuss our findings and display our maps, we encourage you to remember that each data point we collected represents the real, lived experiences of Black performers, and that each performance existed within a complex web of social, economic, and racial realities.

What motivated this project? Why is it important? To what scholarly conversation or community need does it respond?

This project is motivated by the continued relevance of minstrelsy in American popular culture. Traces of minstrelsy pollute almost every aspect of American life including but not limited to our favorite cartoons, folk tunes, and even our laws. Ironically, even with all the remnants of minstrelsy that infiltrate our daily experiences, many Americans are not even aware of what a minstrel troupe is.

In addition to raising awareness and understanding of minstrel troupes as a relevant part of today’s culture, another motivation for this project was to counter the underrepresentation of Black minstrel troupes in research. Previous research surrounding minstrel troupes tends to focus on better known white troupes, so in consequence, there is much research still to be done on Black minstrel troupes. Furthermore, the very existence of Black performers taking part in the racist tradition of minstrel performances emphasizes a more nuanced history that deserves more reflection. Exploring this history can tell us more about Black performers’ possible desire to rebrand this racist art form, the fascination of audiences with “authentic” Black minstrels, and the ways in which the entertainment industry today might be similar to this not-so-distant past.

As we try to spread awareness about minstrelsy (and more specifically Black minstrelsy) to future generations, it is important to start curating tools to better understand and visualize this history as well as create resources for educators. We hope that the maps we have made could help teachers show students a visual representation of how widespread this performance practice was as well as provide a visual aid based on primary sources of the differences in performance locations for Black managed and white managed troupes. Using our maps, we hope that students can generate their own claims about Black minstrelsy instead of blindly believing what they read in a textbook. Additionally, it is important that educators teach this sensitive material in a manner that is appropriate for students. We recommend that teachers always include content warnings before showing visuals or provoking media and before the discussion of this topic generally. Teachers should be able to provide students with resources for managing emotional trauma such as a school counselor. Finally, it is crucial that teachers emphasize that minstrelsy is a tradition that is very much still alive in our world today rather than a cultural tradition that remains in the past. This will legitimize students’ frustration with our current climate surrounding racism and media and prompt them to continue having these discussions outside of the classroom.

Our data collection and mapping respond to the current scholarly discourse by filling a gap in research that may have been more difficult to fill until now. The newspaper databases that we have access to now are more advanced than they were just ten years ago. More historical newspapers are now digitized, and search tools are more precise than ever before. Thanks to these circumstances, our research has been able to add to the current conversation surrounding this topic, simply because we are able to take advantage of resources that were not previously available.

You must be logged in to post a comment.