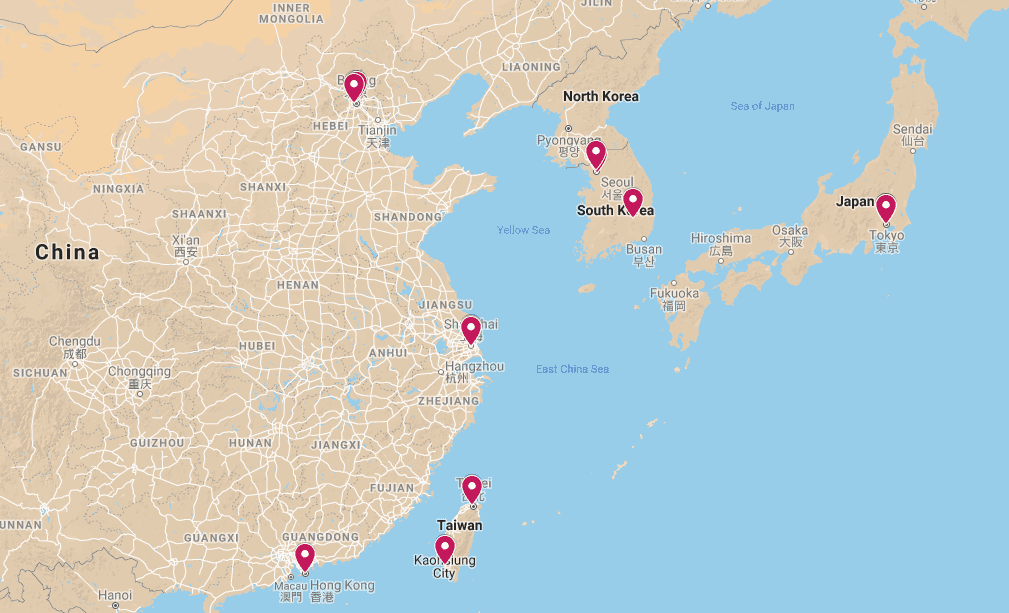

Thus far, my experience making my first map was frustrating primarily because of the research involved. Mapping opera companies of East Asia, much of my work involved reading websites in foreign languages (Chinese, Korean, Japanese), finding mentions of obscure opera companies that had no further leads, and spotty information on opera companies that actually had a chance at being mapped. As a result, my map is far less comprehensive than I initially imagined. For fear of publishing incomplete and/or inaccurate information, there are a number of companies that I did not include in my map. As you can see in my map below, I have several points plotted in my work yet there are a number of companies that do exist between these points that I have not plotted. Unfortunately, this is only a screenshot – you can click here to open up a new blog post in which I embed the most recent version of this map. This map is not a finished product!

I point out the problems with this map not because I mean to undermine the work I have done, but rather to present a disclaimer. In fact, this being my first map, I see it more as a learning opportunity than a perfect product. In her chapter “How to Play with Maps,” Bethany Nowviskie explains the concept of “playing” with maps as the exploration of using maps and their associated tools more as researchers move “towards hands-on analysis, materialized synthesis, and active representation and manipulation of the cultural record.”1 She wants maps and GIS to serve as tools by which scholars of the humanities can reflect on alter the “construction of [their] disciplines.”2 I think Nowviskie’s chapter speaks to me because she would be primarily interested in me learning about my own discipline, musicology, through mapping.

By making this map, I have learned that when researching, especially researching in the pursuit of obscure and foreign music practices, one requires an ability to pinpoint specific data points that may be from a wide variety of sources and synthesize them. The need for finding laser-specific data points comes from the fact that there are numerous websites and articles that state conflicting or confusing facts. Many of these data points are hard to find and tucked away in the bowels of the internet and various databases, or written in foreign languages. Much improvement could be made on my current map with better researching abilities and understanding of the foreign languages. These are all ongoing learning processes, however; they are skills which I am continually bettering as I continue my work on this map and in this course.

Process over product – that’s the spirit! I hope you continue to think of this particular map as a jumping-off point rather than a map that definitively answers a question. One of the fun things about research is that it’s circular: you have an idea, find some but not all answers, and then you refine your idea based on the new information you have, and you go look for more answers. I wonder what new ideas your map of east Asian opera companies will inspire?