From the desk of the Choirmaster of the Rouen Cathedral

15 April, 1929

To the family of Bernard Baudin1,

It is my understanding that your family is in the process of discerning where in Paris our most talented young parishioner shall attend school in the upcoming year to continue with his musical education. It is my conviction that Bernard would do well to seriously consider attending the Paris Schola Cantorum, that wonderful institution which bridges artistry and technical development while still maintaining close ties to the traditions of the Catholic Church. I am aware that there exist those in our community who continue to uphold the merits of the Paris Conservatoire over those of the Schola; however, I will argue that the Schola Cantorum is a preferable choice for the training of an aspiring Cathedral musician and composer due to its rigorous coursework that prepares a truly French artist in his work in the Catholic musical tradition.

I must begin by conceding that many have found the Conservatoire to be the strongest force in educating those at the forefront of French composition, and those people will cite to you the importance of continuing in the great lineage of those who have studied there and have since changed the face of music.2 In fact, however, the best of the Conservatoire education is present in that of the Schola Cantorum. This is unsurprising given that Vincent d’Indy, the dynamic leader of the Schola Cantorum, was educated at the Conservatoire and was later asked to serve on the committee to revise their compositional curriculum.3 It is clear that d’Indy carried the recommendations of this committee – chiefly that the composition courses be broken down into the two distinct foci of craft and style – into his work in developing the curriculum at his own institution in later years.4 Furthermore, the academic operations of the two schools are not terribly different: at the Schola, one receives similar kinds of assessments, styles of grading, diplomas, and performance opportunities as at the Conservatoire.5 Thus, you all need not be afraid of what your Bernard might miss by way of traditional Conservatoire-style academic schooling should he elect to attend the Schola Cantorum.

Despite these similarities, I maintain that the teaching that occurs within the walls of that beautiful English monastery building of the Schola6 is far superior to that of the Conservatoire. First, the training of d’Indy is unparalleled in its rigor and seriousness: the composition classes of this master may take anywhere from seven to ten years to fully complete.7 Lest this frighten you, imagine the depths of knowledge from which your Bernard could pull during such a length of time with a master such as d’Indy; indeed, d’Indy himself is the one who hears the biannual exams of music students at the Schola,8 clear evidence that the students are able to interact not only with their immediate teachers but with that illustrious head of the institution himself.

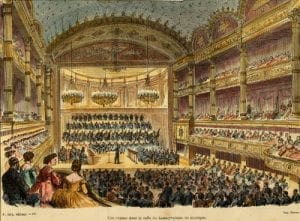

I have sufficiently proven the academic merit of the Schola Cantorum, but surely you are interested in the ways in which your young musician could be formed in his distinctly French artistry by such schooling. In his manifesto for the school, d’Indy clearly outlined his intention that the institution not be viewed simply as a “trade school,” mechanically educating students in a professional realm and then letting them loose to practice their robotic skills however they please. No, d’Indy intends that the Schola function for the purpose of training up true French artists. Nowhere is this more evident than in the marriage between study and performance found at this institution: the Schola holds concerts twice monthly,9 with programming that spans the great music of the ages, often focusing on the important revival of early French music by the likes of Rameau and Gluck.10 Not only do the students at the Schola Cantorum study this music (and study they do – early fugal counterpoint is central to the makeup of d’Indy’s composition classes!)11, but they also perform it, and in performing it, implicate themselves within the long line of great French music.

All this French artistry is, however, rendered useless for Bernard unless in the servitude of the church musician’s true purpose to uphold and communicate the teachings of the Church. It is with this most pressing point that I leave you at the close of my argument: that the training at the Schola Cantorum, as opposed to the Conservatoire, provides an ideal setting for the training of a future Cathedral musician. Perhaps you have heard rumor of Camille Saint-Saëns’ scathing comments condemning the work of Vincent d’Indy: that he “places art on a level with religious faith, demanding from the artist the three theological virtues – faith, hope and charity – and not only faith in art, but faith in God!”12 The author’s incredulity at such a demand reveals the typical attitude of a Conservatoire-educated musician; would that your Bernard could be educated at a place where his faith in God is encouraged rather than treated as an object of ridicule! At the Schola Cantorum, composition students study and perform Gregorian chant and Counter-Reformation polyphony,13 the very gems of our faith tradition, and all are required to sing in a choral ensemble.14 This cultivation of community grounded in Catholic tradition provides a musical environment in which students are emboldened to live into the continuity between their church affiliations and their musical education. Claude Debussy himself said as much in his comments of a concert he attended at the Schola of the music of Rameau: “I don’t know if it is because of the smallness of the room, or because of some mysterious influence of the divine, but there is a real communion between those who play and those who listen.”15

It is thus with great conviction that I recommend the institution of the Schola Cantorum, rather than the Paris Conservatoire, as the place where Bernard should further his musical education. The unparalleled instruction in composition, emphasis on the cultivation of French artistry, and infusion of academic with religious life all combine to make the Schola a school in which the aspiring Cathedral musician and composer would flourish beautifully!

1This is a fictional name; any parallels to a historical figure are purely coincidental.

2. Harold Bauer, “The Paris Conservatoire: Some Reminiscences,” in The Musical Quarterly 33, no.4 (October 1947): 533-542, accessed 9 November, 2015, http://www.jstor.org/stable/739325?pq- origsite=summon&seq=2#page_scan_tab_contents.

3. Jann Pasler, “Deconstructing d’Indy, or the Problem of a Composer’s Reputation,” in 19th-Century Music 30, no. 3 (Spring 2007): 240, accessed 23 October, 2015, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/ncm.2007.30.3.230?pq-origsite=summon.

4.. Andrew Thomson, Vincent D’Indy and His World (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 118.

5. Pasler, 246.

6. Ibid., 116.

7. Norman Demuth, Vincent D’Indy: Champion of Classicism (London: Rockliff Publishing Corporation, 1951), 20.

8. Thomson, 125.

9Thomson, 125.

10Pasler, 252.

11Ibid., 248.

12Camille Saint-Saëns, Outspoken Essays on Music (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1922), 2.

13. Brian Hart, “Vincent d’Indy et son temps,” in Music and Letters 89, no. 2 (May 2008): 265, accessed 20 October, 2015, http://ml.oxfordjournals.org/content/89/2/261.full.pdf+html.

14. Thomson, 124.

15. Claude Debussy, Debussy on Music, ed. Richard Langham Smith (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1971), 111.

You must be logged in to post a comment.