Racism & Reception in the U.S and Abroad

Lillian Evanti, a native of Washington D.C, made the difficult decision to move to Europe to continue her education in Paris, “where her opportunities were not as limited by discrimination” . Though she had performed in many locations in the U.S, one of her only known performances in a desegregated theater was at the Belasco Theater in Washington DC. Evanti declared, “I’m going to learn to sing professionally under the best vocal teacher in Paris, then come back here and show what I can do”.

Her peers agreed that in order to be taken seriously by American critics, she would likely have to follow suit of other black musicians and seek European accolades. During the following 20-30 years Evanti spent time in Europe, toured South America, Africa, and the Caribbean, and made frequent returns to the United States where critics had finally begun to take her seriously. Unfortunately, the “New York City opera gatekeepers were not so welcoming”. Despite her many auditions and acclaimed roles, she was never offered a role with the Metropolitan Opera. It took until 1955 for Marian Anderson to become the first African American opera singer to be part of the Metropolitan Opera.

Evanti’s correspondence shows how adamantly she fought to achieve the career she had. An exchange of letters with the Bavarian Minister of State, A. Schemm, depicts how Evanti had been investigating her ability to attend higher education in Bavaria, and clarifying that there would be no barriers to admittance for a woman of color. She also corresponded with scholar, activist, and music-lover W.E.B. Du Bois, who also served as editor of the journal The Crisis. DuBois frequently featured Evanti in his paper, even publishing one particular letter verbatim in a Crisis article. This letter pleaded against segregated audiences in the United States and urged American audience members to attend every concert, not just the performances of artists from their own cultures. Evanti had a clear passion for activism and social justice which intermingled with her determination and dedication to the performing arts.

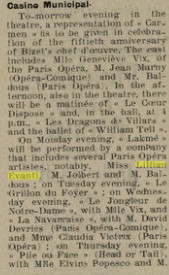

Newspapers everywhere sang the praises of Lillian Evanti in a number of ways. Black newspapers and journals had been adamantly in support of her career from the very beginning, with her early concerts in Washington DC, but white critics were slower to accept her excellence. For many years, predominantly white papers in America held simple advertisements for her recitals, and only really began to publish rave reviews after she had found acclaim in Europe. European papers appeared to be less segregated, and critics were simply enchanted by her voice.

Photos Cited

Figure 1: Portrait of Lillian Evans Tibbs Evanti, Smithsonian American Art Museum Collection, 1937. Photograph. https://womenshistory.si.edu/herstory/entertainment/object/madame-lillian-evanti

Figure 2: W.E.B Du Bois with Lillian Evanti and Vada Somerville, Los Angeles, 1947. W.E.B Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections adn University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

Figure 3: Anon. “The Menton & Monte Carlo News with List of Visitors .” News from Nice, March 7, 1925.