Native American Song Collection

Frances Densmore

Frances Densmore was one of the first ethnomusicologists to study Native American music in the United States. She dedicated 40 years of her life traveling throughout the Northern Hemisphere. She spent time with more than 20 tribes across the United States as well as British Columbia and Panama. With funding from the Smithsonian, she published bulletins about each of her expeditions that included in-depth, scientific-style analyses of the music she collected, often written using standard Western musical language and featuring detailed data tables.

Why did Frances Densmore feel so obligated to collect Indigenous song?

Historian Michelle Wick Patterson presents Densmore’s classic response to this question in the following way:

“‘I heard an Indian drum.’ Densmore would then relate the story of how as a young girl she often fell asleep to the distant sound of the drumming of her Dakota neighbors on an island near her hometown of Red Wing, Minnesota. These sounds, she contended, somehow became a part of her, constantly calling her back home and reminding her of some larger work to do.” 1

The truth is undoubtedly more complicated than what Michelle Wick Patterson presents. Densmore displayed a prevailing attitude towards Native Americans that was common among settlers at the time: that of the “Vanishing Indian.” The “Vanishing Indian” mentality positions Indigenous people as artifacts of the past; imagining Native Americans as already disappearing, settlers could more concretely construct an American frontier identity. Densmore and others felt obligated to observe and collect artifacts, in her case music, which could remain after the living culture of Indigenous tribes would inevitably die out.

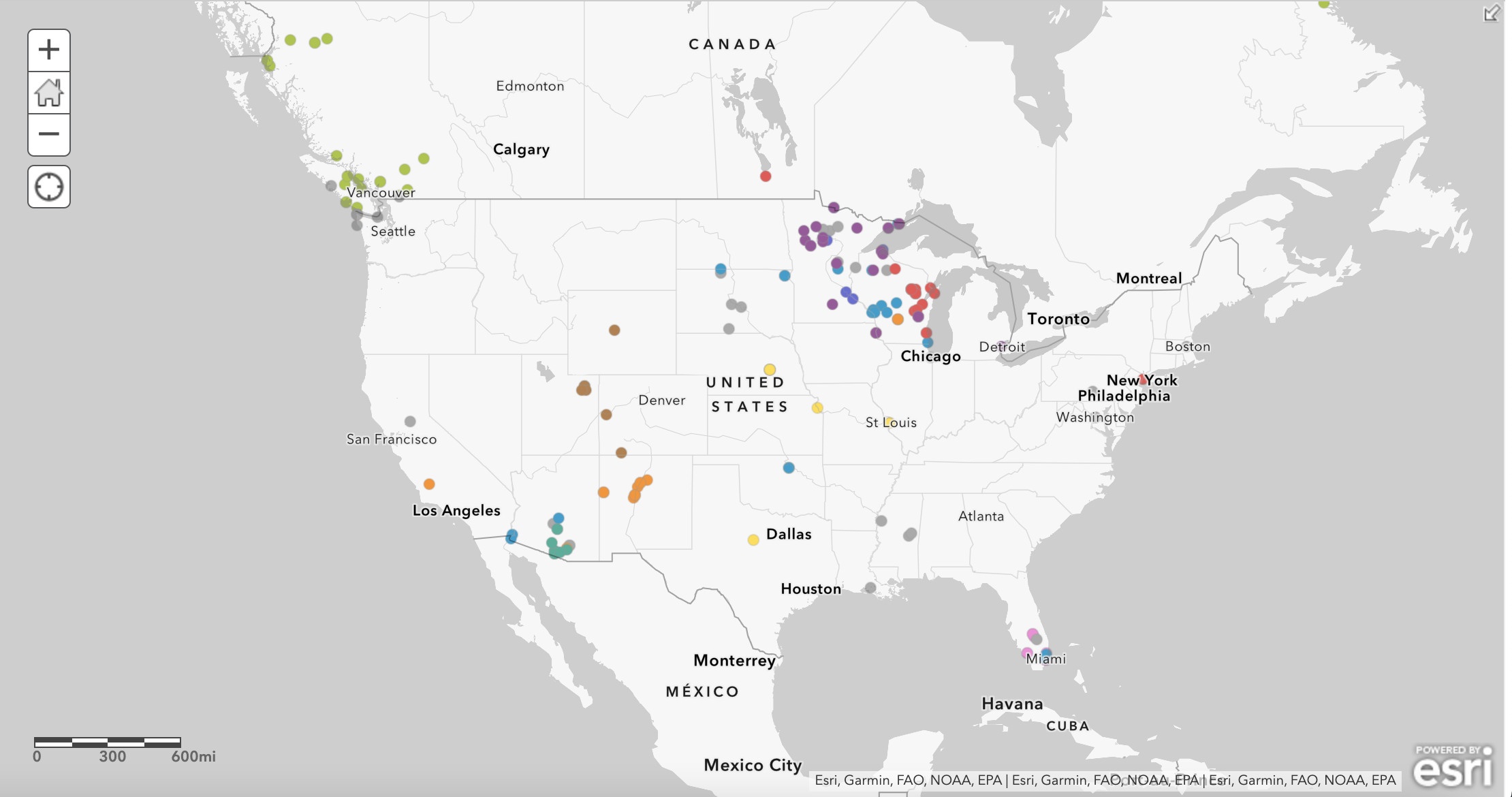

Map Information

This map reflects major trends in Densmore’s song collecting activities. We’ve incorporated all of Densmore’s Smithsonian bulletins for the Bureau of Ethnology and some of her other publications as we’ve had access to them. The markers on this map represent songs that Densmore explicitly tied to specific locations. Clusters appear in certain regions, particularly the Midwest, because she published multiple “bulletins” while working for the Bureau of Ethnology that refer to the same place-linked songs. It is important to note that we only plotted data on our maps that tied specific musical events with locations — many of the songs and musical events described in Densmore’s bulletins lack attribution to individuals or to places.

This map features multiple layers consisting of data from Frances Densmore’s Smithsonian bulletins and a layer from Native Land Digital. Native Land Digital is a changing map; the boundaries it presents do not necessarily reflect official legal borders of any Indigenous nations. This project is a work in progress and is constantly evolving with new input and feedback from Indigenous communities.

Although Frances Densmore is celebrated by many historians, musicologists, and ethnographers for her work in cultural preservation, Densmore also harmed the Native American communities she studied by intruding into sacred cultural practices and being complicit in the government’s erasure of their sovereignty.

Considering Different Perspectives on Densmore’s Collecting Activities

There is no mutual consensus over the value of Densmore’s song collecting activities. The legacy of her work and the far reaching scope of her collecting projects means that they have had an impact on many individuals or communities whether that be positive or negative. While some point towards song collection as a culturally contentious practice, Dylan Robinson’s book points out that:

“During the height of ethnographic song collection in the early twentieth century, many Indigenous leaders were convinced that sharing their songs with ethnographers would keep them safe for future generations.” 2

Densmore’s work presents several challenges. The United States government hired Densmore to collect the music of Indigenous people in order to solve, what they saw to be, the problem of the inevitable disappearance of Indigenous culture. Though this is an important problem to acknowledge, the very government that sponsored much of Densmore’s work was the same government that was causing the problem that they identified. Irrespective of whether the Indigenous peoples that Densmore worked with were supportive of her work, the amount of collecting work that she did could reveal larger scale issues with representation of various Indigenous cultures. Looking at the sheer amount of recording work that Densmore did and the large geographic spread over which she took these recordings, it is clear that her work lacked the amount of focus necessary to adequately understand and respect the cultural traditions she was trying to preserve. Densmore’s mindset also alludes to cultural assimiliation— like many who worked with Indigenous individuals during Densmore’s lifetime, she firmly believed that she was doing a service to Indigenous groups by supporting them and assisting with their assimilation into the American lifestyle.

Despite the aforementioned problems that are often observed with Densmore’s work, many believe that Densmore’s work is valuable as it creates records of history that are now widely accessible to a variety of audiences. Additionally, the recordings that Densmore made do give us information about Indigenous music that we would not otherwise have had access to and many emphasize the value that these recordings give to the study of Indigenous music and culture today.

Densmore’s work with Smithsonian underscores many complexities to the collection and recording of Indigenous songs. However, stopping at the recognition of Densmore’s work severely underemphasizes the implications of her work in a contemporary context. Today, scholars’ and artists’ active engagement with collected materials and their repatriation support the recontextualization of her work and illuminate the value of continued repatriation efforts.

Repatriation

What is repatriation*?

Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) defines repatriation as “the process whereby human remains and certain types of cultural items are returned to lineal descendants, Indian tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations.” 3 Most frequently, repatriation entails the return of human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, objects of cultural patrimony, and illegally acquired objects. NMAI’s “A Step-by-Step Guide through the Repatriation Process” details the Smithsonian’s processes for repatriation. Though different institutions have different processes, NMAI offers an excellent model for understanding general processes for repatriation.

*This definition of repatriation is the most traditional definition of the term. Throughout the prose and in our map, we offer several complications to this definition, but for the purpose of an overview we’ve chosen to present the NMAI’s definition of repatriation in the broadest sense of the term.

Why is it important?

In the spirit of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, considering the universal framework for the dignity and well-being of Indigenous peoples entails the proper treatment of Indigenous property and the return of items of cultural patrimony and sacred importance. Repatriation of these items preserves cultural heritage and re-establishes cultural authority over items removed from communities without consent.

How do people do it?

A discussion with longtime Repatriation Coordinator Terry Snowball revealed several important insights into the complexity and nuance of repatriation. Snowball, a member of the Prairie Band Potawatomi/Wisconsin Ho-Chunk Nation, has been working on the NMAI’s repatriation efforts since the 1990s when he began working in the museum’s collections. Snowball’s primary work is concerned with the repatriation of physical remains, something that he described as the most traditional model of repatriation. To summarize the process of repatriating any physical object, he emphasized the community-based efforts that are necessary to any object’s repatriation process. His work is people-centered and he prefers to call himself and his coworkers stewards of the NMAI’s collections rather than owners. Essentially, except within the case of human remains, repatriation involves inquiry into the ownership of the object. After a descendent or member of a group lays claim to an object, a team of researchers is assigned to a case. Those researchers have the goal of objectively gathering any information that can establish the lineage of an item and affirm an item’s cultural affiliation. This information is often acquired through textbook-style research but it can also be gathered from oral histories, stories and songs.

Repatriation is a nuanced category. Snowball’s experiences with repatriation highlight some of its most traditional forms. When considering the repatriation of recorded materials, the process becomes a little more challenging. One standardized form of repatriation of digital materials does not exist. Given the breadth and coverage of the internet, it is not easy to simply remove or reestablish ownership of Indigenous recordings. So, scholars like Lyz Jaakola and Trevor Reed have considered the ways in which recordings could be alternatively repatriated, especially when there is conflict regarding the patrimony of a recording or there are multiple individuals who could lay claim to an item like a sound recording. Jaakola, for example, emphasizes the recontextualization of the recordings. Working with current Indigenous community members to re-record and recontextualize those recordings that had largely been removed from their contexts on wax cylinders like in the case with Densmore or other song collectors.

Data Disclaimer

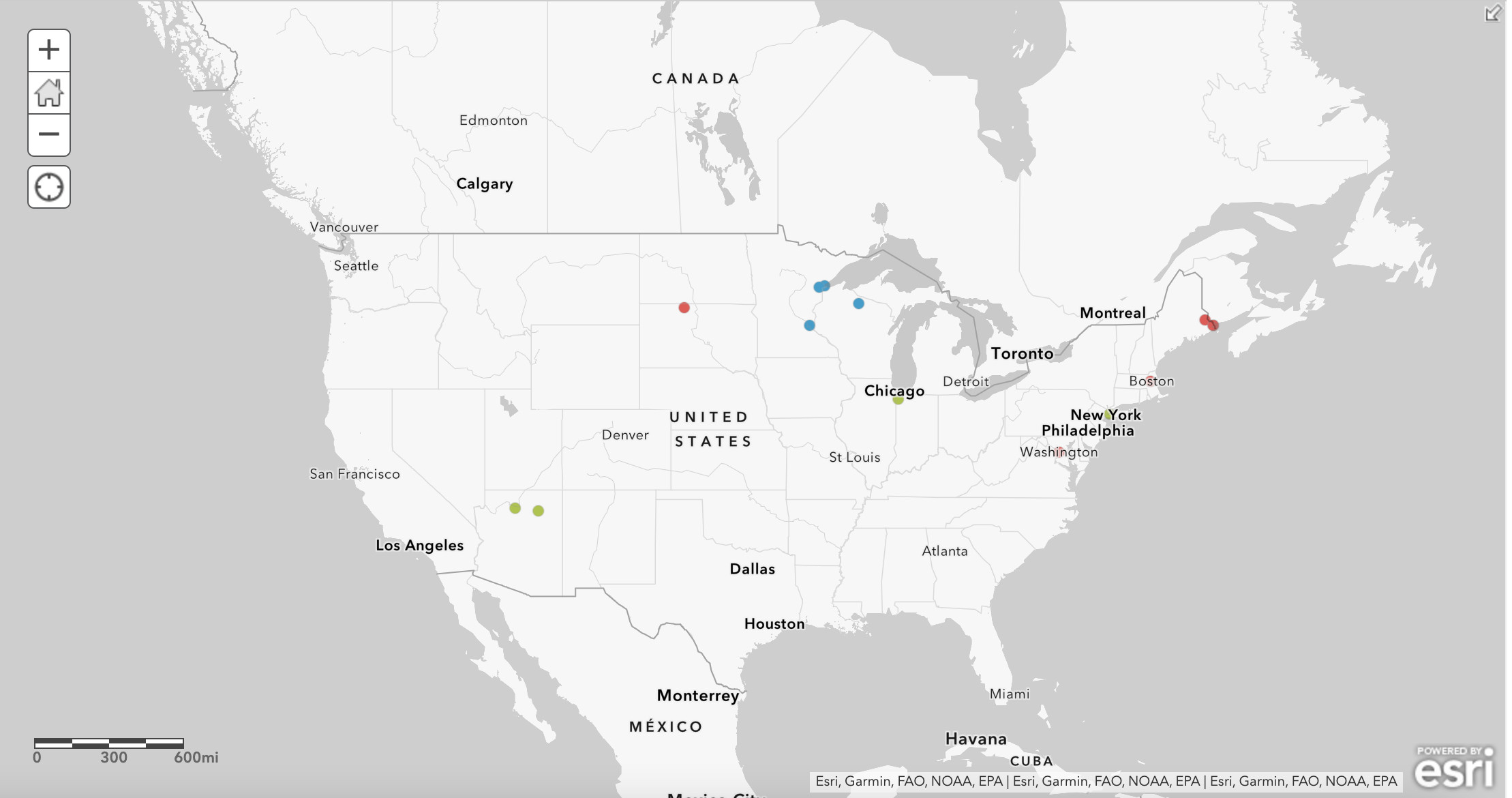

The repatriation map presents the movement of recordings repatriated by three contemporary scholars who work with digital repatriation of Indigenous sound\recordings. Lyz Jaakola’s work with repatriation is the only work represented on this map that explicitly deals with recordings made by Frances Densmore.

Repatriation Experts

Trevor Reed

Trevor Reed is currently an Associate Professor of Law at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University. He received a joint PhD and JD in Ethnomusicology and Law at Columbia University where he wrote his dissertation “Sonic Sovereignty: Hopi Song, Indigenous Authority, and Intellectual Property in an Era of Settler-Colonialism.” During his time at Columbia, he directed the Hopi Music Repatriation Project (HMP), in collaboration with Columbia’s Center for Ethnomusicology and the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office.

Lyz Jaakola

One way we can support Indigenous ownership of their music is by listening to music created and produced by Indigenous artists. This Youtube playlist contains a few examples, including music by Lyz Jaakola.

E. Tammy Kim

The map on the left contains data from Densmore bulletins, while the map on the right contains data from the repatriation experts. The work to return music and other artifacts has really only begun, as you can see from the sheer difference in data points.

Densmore Data Points

Repatriation Data Points

Calls to Action

Repatriation is a long and complex process. Active involvement in repatriation work is certainly one way to support Indigenous artists and their cultural products, but there are other options too! Though this project does not touch on these concepts with an immense amount of detail, it is worth highlighting several opportunities that are easily accessible and can support efforts in understanding privilege and recontextualizing the products of Frances Densmore’s and others’ song collecting activities.

Land Acknowledgements

Land acknowledgements are an important and easy way to engage with Indigenous communities and acknowledge which land you’re residing on or visiting. A land acknowledgement formally recognizes Indigenous people as stewards of the land and highlights the relationship between Indigenous people and their traditional territory. Land acknowledgements are active and recognize the ongoing impact of colonialism and largely exist to promote mindfulness about the land we now occupy.

St. Olaf College’s land acknowledgement reads:

“We stand on the homelands of the Wahpekute Band of the Dakota Nation. We honor with gratitude the people who have stewarded the land throughout the generations and their ongoing contributions to this region. We acknowledge the ongoing injustices that we have committed against the Dakota Nation, and we wish to interrupt this legacy, beginning with acts of healing and honest storytelling about this place.”

Writing formal land acknowledgements is one route that many choose to take as they take up residence on Indigenous land. The Native Governance Center offers a very useful guide to tips about writing a land acknowledgment. If you’re not sure which land you’re on, texting your zipcode to (907) 312-5085 can give you information and facilitate the start of the land acknowledgement writing process.

Decolonizing Listening Practices

Dylan Robinson’s book Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies considers listening from Indigenous and settler colonial perspectives and argues that decolonial listening practices emerge by increasing the awareness of our position as listeners. His book provides one valuable perspective on how one can consider listening to music made by Indigenous people. Consider some of Robinson’s thoughts below in listening to any of the recordings on our playlist:

“Foundational differences between Indigenous and settler modes of listening are guided by their respective ontologies of song and music. Western music is largely though not exclusively oriented toward aesthetic contemplation and for the affordances it provides…” 4

“Indigenous ontologies of song ask us to reorient what we think we are listening to and how we go about our practices of listening with responsibilities to listen differently, while also requiring us to examine how we have become fixated- how listening has in effect been ‘fixed’- in practices of aesthetic contemplation, as a pastime or entertainment, and through its various affordances. In reorienting our listening practices from normative settler and multicultural forms to the agonistic and irreducibly sovereign forms of listening, we must also reconsider what we think we are listening to.” 5

“Redressing forms of hungry listening- both the ‘fixing’ of listening and listening that fixates upon the resources provided by musical content- requires some ontological reorientation of what we believe we are listening to when we listen to Indigenous music and Indigenous+Western art music.” 6

“Understanding practices of Indigenous listening resurgence necessitates more than gaining a mere awareness of the diverse cultural context and cultural protocol of Indigenous communities. To gain even partial understanding of these practices requires developing relationships with Indigenous artists, singers, and knowledge keepers.” 7

Donating Time and/or Money

Listed below are some organizations that work with Indigenous artists and/or members of Indigenous communities. There are many other organizations that do valuable work in related areas and the list below are just suggestions for places to start.

Acknowledgements and Further Data

This research was done by Emmie Head, Mark Jesmer, Anna Severtson, Kalli Sobania, and Greta Van Loon. Click here to access our research, including all our mapped data, photos and music from Densmore’s research, and a picture of the researchers!

Our research process would not have been possible without the support and assistance of various St. Olaf community members. Special thanks to Professor Louis Epstein for his support and guidance throughout the completion of this project for his course “Race, Identity and Representation in American Music.” St. Olaf’s own resident mapping expert Sara Dale offered much support and encouragement as we learned how to navigate ArcGIS.

Beyond the St. Olaf community, Government Documents Librarian Katie Lewis from Carleton College helped us locate physical copies of all of Densmore’s Smithsonian bulletins housed in their documents collection. Terry Snowball, a repatriation coordinator with the NMAI kickstarted the repatriation portion of our research and provided an invaluable perspective on the challenges with digital repatriation and standard repatriation processes more broadly.

Footnotes

1 Michelle Wick Patterson. “She Always Said, ‘I Heard an Indian Drum.’” In Travels with Frances Densmore: Her Life, Work, and Legacy in Native American Studies, edited by Michelle Wick Patterson and Joan M. Jensen, 29–64. University of Nebraska Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1d98bg6.6.

2 Dylan Robinson, Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, 150.

3 “Repatriation.” National Museum of the American Indian. Smithsonian, Accessed December 9, 2021. https://americanindian.si.edu/explore/repatriation