Scroll down to read about the project, see the maps, and find other related information. Or, use the navigation center below.

“In order that the center can not only advise, convince, and debate with the orchestra— as has been the case up to now— but really to direct it, we need detailed information: who is playing which violin and where? What instrument is being mastered and has been mastered and where? Who is playing a false note (when the music starts to grate on the ear)—and where and why? Whom to relocate to where and how in order to correct the dissonance. –Vladimir Lenin, What is to Be Done? (1902)”

Introduction/About

The other two maps, following the gulag experiences of Tamara Petkevich (with TEC) and Lina Prokofiev (wife of Sergei), aim to show an in-depth look at the necessity and effects of music in the gulag. In Tamara’s map, you can find some of the repertoire performed in the gulag and how the touring worked. In addition, you can read about her intricate social relationships and personal life – almost all revolving around her involvement in the performance theater in the Knazh-Pogost camp. Lina’s story follows her desires and letters to her sons while she was incarcerated. She was imprisoned due to the inquiries into Sergei’s work, and yet he never once wrote to her during her time in prison and the labor camps. So, she asked her sons to send her songs, scores, and other materials. In addition, she sang and conducted a great deal in the camps of the far north and south of Moscow. These personal stories give us not only quantitative data on repertoire, number of performances, and locations, but also give us more critical and humanistic accounts of the events that transpired.

In order to see all three maps together in an ArcGIS storymap, follow the link here.

This project was created as a part of the Musical Geographies research course at St. Olaf College. Most of the information was collected through traditional scholarly research; almost all information was taken from memoirs and first-hand accounts of the gulag by its survivors. See the bibliography below for more of the sources and for external links to helpful sites.

“But the soloists in our collective did not want to sing in unison, Then I understood why the Party didn’t care for the intelligentsia – it does not want to sing in unison.” – Kamil Ikramov quoted in The Soviet Theater: A Documentary History by Laurence Senelick

The Maps

General Overview Map

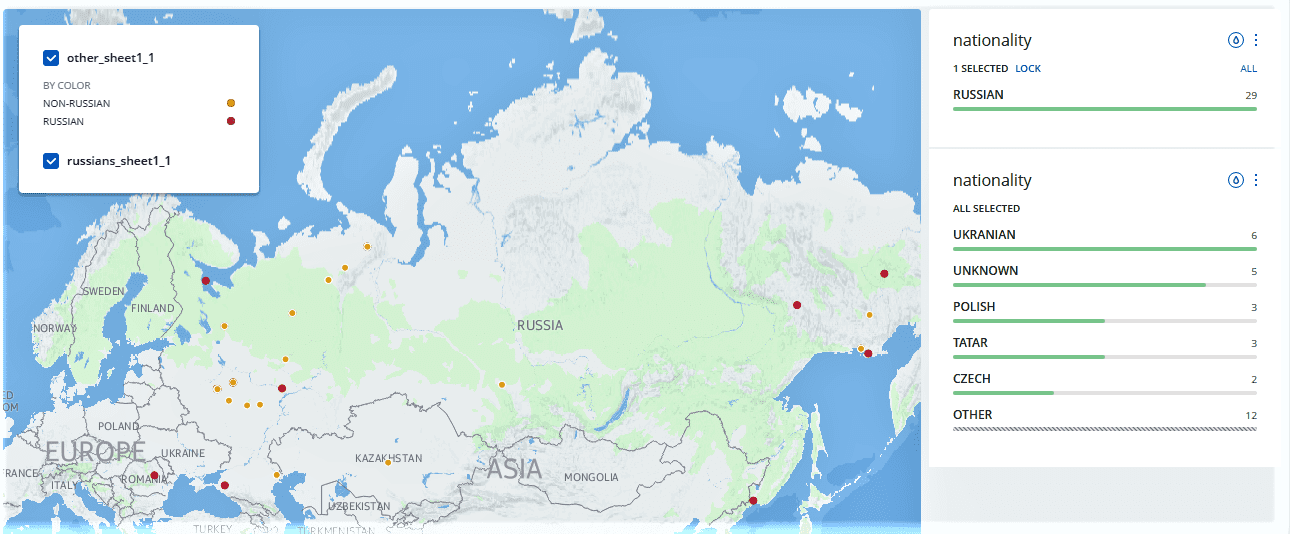

This map of several layers shows musical events (public and private), people of musical relevance, and general information about the Gulag (Main Department of Labor Camps). Click the button in the top left hand corner of this map to see the layers and color designations of people’s nationalities.

Click on markers, polygons, and routes in the key and on the map in order to learn more about how music found itself integral to the lives of the prisoners.

Theater Ensemble Collective (TEC) Map

This narrative map moves through the parts of Tamara Petkevich’s life that involved TEC (Theater Ensemble Collective). Most “respectable” camps created their own theater companies over the years, though only a few were as popular as TEC (based in Knyazh – Pogost camp in Urdoma district, a part of the Northern Railway Camps).

Click through the events on the bottom bar, and scroll through the text in the accompanying window to learn more about Tamara’s experience with TEC. This map is best viewed on a laptop or desktop computer.

Tamara was arrested January 30, 1943, and released January 3, 1950. While imprisoned, she was a nurse and, later, an actress. As an amateur, Tamara brought excellent oration skills to the theater company and learned singing and dancing skills while in the camps. The company performed across the Western camps. In this storymap, we explore TEC through Tamara’s experiences. Thus, the story map by no means contains comprehensive information on the entire history of TEC, only those for which we have information through her memoir.

A note on sources: Unless otherwise noted, all information comes from Tamara’s Memoir. It was originally titled Life is an Unmatched Boot, re-titled with author’s permission by the editors of the English translation, Memoir of a Gulag Actress. All photos should have a link to the photo source in the description. Few are from actual TEC performances, but they give an accurate representation of the things TEC performers would have seen and experienced. No photos are owned by St. Olaf College or affiliates with this project

To open the storymap in ArcGIS or a new tab, click here.

Sources:

Senelick, Laurence, and Sergei Ostrovsky, eds. The Soviet Theater: A Documentary History. Yale University Press, 2014.

Petkevich, Tamara. Memoir of a Gulag Actress, trans. Yasha Klotts and Ross Ufberg. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2010.

Lina Prokofiev Map

Lina Prokofiev (Carolina Codina), Spanish wife of Sergei Prokofiev (also a successful soprano), was imprisoned from Feb. 20, 1948 – June 13 1956. This map explores her movement through the Gulag as she was relocated to several different camps. Additionally, it follows her experiences performing and conducting music, mainly while at Inta, Abez, and Kirov labor camps.

Click the down arrow in the storymap to begin the tour, and scroll through each of her stops along the way. Feel free to interact with the map and click on the points, as well as the audio and video included in the slides themselves. To open the map in ArcGIS or a new tab, click here.

All information, unless otherwise noted, has been collected from Simon Morrison’s Lina and Serge: The Love and Wars of Lina Prokofiev (2013).

In 2007, Russian schoolbooks were rewritten in order to to omit any mention of the Gulag or Stalin’s murder of millions of citizens. Many Russians polled view him as the greatest Russian in history.

Glossary

Zek: Gulag returnees/survivors

Gulag: Main department of Corrective Labor Camps or “General Directorate of Camps” (literal translation)

Quotes

“Who among us has not experienced its all-encompassing embrace? In all truth, there is no step, thought, action, or lack of action under the heavens which could not be punished by the heavy hand of Article 58.” – Alexander Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago

“It would require tremendous imagination to fathom what such a theater meant for the children of prisoners. Camp children didn’t know what freedom was; they had never seen a caw or a chicken or daisies in the field . . . When a puppet dog appeared on the stage as a character in one of the shows, the children burst into tears and it was impossible to calm them down. The performance had to be stopped. After one performance of the Nightingale, a boy about five years old ran up to Tamara [Grigoriovich] and gingerly touched her dress with his index finger . . . the boy lifted his eyes and said in a quiet and secret voice “I love you, Aunty.” He did not know Tamara’s name . . . but somehow the songbird from the play stirred an unfamiliar feeling of joy and anguish in him and awakened the little boy’s soul.” – Tamara Petkevich, Memoir of a Gulag Actress

“When [TEC] approached an orphanage, a flock of [children] rushed toward us and hastily pushed small paper packages into each of our hands . . . Wrapped in each package, made of notebook paper covered in writing, there was a carrot and couple of lumps of sugar. A hoarse roar betrayed the chief escort guard. Unable to bear the scene, he was the first to burst into tears. They must have prepared the children long in advance. What did they manage to instill in them, in those hungry years after the war, which made them willing to share their meager food rations with prisoners?” Tamara Petkevich, on TEC’s encounters with local children, Memoir of a Gulag Actress

“You loved people, You helped them live, You will always be with us, Alive, unfailing and loved.” – Epitaph on the grave of Aleksandr Osipovich Gavronsky, former artistic director of TEC (1888 – 1958)

“The range of religious beliefs was astonishing . . . In the summertime you could see them all in the corner of the camp we called the “park.” Every birch tree was a chapel of sorts.” – Nina Gagen-Torn, from “On Faith” in Gulag Voices by Anne Applebaum

“I write in the name of the living, / That they, in turn, may not stand / In a silent, submissive crowd / by the dark gates of some camp.” – Yelena Vladimirova. “Kolyma”

Bibliography

Applebaum, Anne. Gulag: A History. New York: Random House, 2003.

Applebaum, Anne, ed. Gulag Voices: An Anthology. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

Bakst, James. A History of Russian-Soviet Music. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1977.

Birch, Douglas. “The Art of Surviving the Gulag: Drama: Through theatrical performances, actors in the Soviet prison camps encouraged themselves – and their audiences – to live.” Baltimore Sun, March 9, 2013. http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2003-03-09/news/0303080344_1_gulag-prison-camps-labor-camps

Boer, S.P. et al., Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in the Soviet Union, 1956-1975. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982.

Buckham, Tom et al., “Lost in the Gulag Buffalo Musician, Second City Man Among Victims of Stalin’s Purges.” Buffalo News, November 8, 1997.

Cohen, Stephen F. The Victims Return: Survivors of the Gulag after Stalin. London: I.B. Taurus, 2011.

Draskoczy, Julie S. Belomor: Criminality and Creativity in Stalin’s Gulag. Brighton: Academic Studies, 2014.

Fanning, David. Mieczyslaw Weinberg: In Search of Freedom. Hofheim: Wolke, 2010.

Frovola-Walker, Marina. Russian Music and Nationalism: From Glinka to Stalin. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

Gheith, Jehanne M. and Katherine R. Jolluck. Gulag Voices: Oral Histories of Soviet Incarceration and Exile. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

“The Gulag Museum on Communism.” The Global Museum on Communism, Last modified 2014. http://www.thegulag.org/.

“Gulag: Soviet Forced Labor Camps and the Struggle for Freedom.” Center for History and New Media, George Mason University. Last modified 2017. http://gulaghistory.org/nps/about/.

Ings, Simon. Stalin and the Scientists: A History of Triumph and Tragedy. New York: Grove Atlantic, 2016.

Ivry, Benjamin. “How Mieczyslaw Weinberg’s Music Survived Dictators.” Forward 13, (2010).

Koenker, Diane P. and Ronald D. Bachman. Revelations from the Russian Archives: Documents in English Translation. Washington: Library of Congress, 1997.

Klause, Inna. “Music and ‘Re-Education’ in the Soviet Gulag.” Torture 23, no. 2 (2013).

Krebs, Stanley D., Soviet Composers and the Development of Soviet Music. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1970.

Leonard, Richard Anthony. A History of Russian Music. London: Jarrolds, 1956.

Maes, Francis. A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar. Translated by Arnold and Erica Pomerans. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Mikkonen, Simo. Music and Power in the Soviet 1930’s. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen, 2009.

Morrison, Simon. Lina and Serge: The Love and Wars of Lina Prokofiev. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013.

Nelson, Amy. Music for the Revolution: Musicians and Power in Early Soviet Russia. University Park: Penn State University, 2004.

Olkhovsky, Andrey Vasilyevich. Music Under the Soviets: The Agony of an Art. Studies on the U.S.S.R, No. 11. New York: Published for the Research Program on the U.S.S.R. by F.A. Praeger, 1955.

Petkevich, Tamara. Memoir of a Gulag Actress, trans. Yasha Klotts and Ross Ufberg. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2010.

Raschendörfer, Irina, et al., “Gulag.” Memorial, Berlin/Moscow. Last modified February 2006. http://www.gulag.memorial.de/project.html

Schwarz, Boris. Music and Musical Life in Soviet Russia: 1917 – 1981. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1983.

Senelick, Laurence, and Sergei Ostrovsky, eds. The Soviet Theater: A Documentary History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

Sitsky, Larry. Music of the Repressed Russian Avant-Garde, 1900-1929. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1994,

“Sound Archives: European Memories of the Gulag.” Institut National d’Études Démographiques, Le Centre

National de la Recherche Scientifique. Last modified October 2, 2016. http://museum.gulagmemories.eu/en/home/homepage

Taruskin, Richard. “The Rising Soviet Mists Yield Up Another Voice: Mieczyslaw Weinberg has for the most part remained hidden in Shostakovich’s shadow. A cellist hopes to shed light. The Mists Of Russia Yield Up A Voice” The New York Times, December 3, 1995.

Taruskin, Richard. On Russian Music. Berkeley: University of California, 2009.

Taruskin, Richard. Russian Music at Home and Abroad. Oakland: University of California, 2016.

Toker, Leona. Return from the Archipelago: Narratives of Gulag Survivors. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000.

Vilensky, Simeon, ed. Till My Tale is Told: Women’s Memoirs of the Gulag. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999.

“Virtual Museum of the Gulag,” or “Виртуального музея Гулага.” Research and Information Center “Memorial” (St Petersburg). Last modified 2012. http://gulagmuseum.org/search.do?objectTypeName=images&page=1&language=1

Vizel, Mikhail. “Masterpieces created in the Gulag.” Russia & India Report. Last modified December 25, 2014. http://in.rbth.com/arts/2014/12/25/masterpieces_created_in_the_gulag_40551

Wettstein, Shannon L. “Surviving the Soviet Era: An Analysis of Works by Shostakovich, Schnittke, Denisov, and Ustvolskaya.” PhD diss., University of California, 2000.

Zarod, Kazimierz. Interview by Conrad Wood. “Zarod, Kazimierz Adam (Oral history)” Imperial War Museums. February 12, 1991. http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011625

Related Sites:

http://museum.gulagmemories.eu/en/home/homepage

http://gulaghistory.org/nps/about/

http://www.thegulag.org/

Acknowledgements

St. Olaf College

Simon Morrison

St Olaf Digital Humanities on the Hill Initiative