Introduction

In March of 1926, Milhaud set off for the USSR to give a concert tour with fellow French pianist Jean Wiéner. Milhaud gave three concerts in Leningrad, and three in Moscow. Years later, he devoted nearly four pages in his autobiography My Happy Life to the trip, describing everything from musicians and border guards to clandestine nightclubs.

90 years later, I studied abroad at Yaroslav-the-Wise Novgorod State University in Veliky Novgorod, Russia, and happened to visit many of the places Milhaud did. But the coincidence of our geography doesn’t do justice to either of our experiences; not all history can be told in a map. Who did we meet, what did we see, hear, smell, or taste? What was it like?

Juxtaposing excerpts from Milhaud’s My Happy Life with parts of my own travel journal (adapted and expanded), photos, and sound, I hope to explore what the same place can mean in different times to different people.

Except for two historical photos, all photos are my own. Clicking on the historical photos will take you to their sources.

Contents

Arrivals

March 1926

Crossing the Soviet frontier in the middle of the night was quite impressive. A wooden arch covered with foliage bore a banner with the inscription in several languages: ‘Workers of the world, welcome.’ Soldiers in long great-coats supervized the customs formalities. Newspapers and books received individual attention, as a precaution against any attempt at capitalist infiltration. (My Happy Life 143)

August 2016

Having been to Russia once before in 2011, I expected at least to recognize the airport. But, when I arrived at Pulkovo, I was astonished to find myself walking down completely new glass and steel hallways. Where was the yellowing Soviet concrete, the stench of cigarette? Even the uniformed guards had decided it was alright to take up their posts at customs instead of right in front of the jetway exit. None of my books received any attention at customs, although I did have to convince one suspicious officer that my violin really was mine. (Note to self: put more stamps on documents to speed up the process.)

A taciturn gray-haired man in a fishing vest was waiting to drive me to Veliky Novgorod –the ancient capital of Russia turned provincial post-Soviet city, and my home for the next four months. Leaving the Petersburg metro area around 9 or 10pm, we drove past a huge set of illuminated Egyptian gates and two guys flying what suspiciously looked like a drone carrying a cloth-and-paint banner of Lenin’s head. The silent driver turned on russkiy radio, turning around briefly to ask “Is this normal?” I nodded (who was I to say?), and we sped into the countryside, blasting the booming beats, minor modes, and occasional accordion riffs of russkiy hity past battered dachas and rows of birch trees that lined the highway in the misty darkness.

Drive from St. Petersburg to Novgorod

A City by Two Names

March 1926

Leningrad seemed asleep on the banks of the Neva. Since the Government departments abandoned them, the red and green palaces appeared to have remained uninhabited. The sky was blue, and sun warm, and the thaw had set in. It was a curious sensation not to be able to read the name of a street or boulevard, but the Government made up for this deficiency by supplying a young musician to act as interpreter and go with us wherever we went, to help us in all our difficulties. Every day, the Commissar of Fine Arts responsible for cultural relations rang up to know what we should like to see at the theatre and reserved seats for us. All productions were most elaborate, and enthrallingly interesting. (My Happy Life 143)

2016

Almost 100 years after revolution, St. Petersburg, no longer Leningrad, is anything but asleep. These days, the Commissar of Fine Arts has been replaced by little kiosks sprinkled throughout the city selling the equivalent of 5 dollar tickets for anything from Sting to Swan Lake. The embodiment of imperial grandeur, St. Petersburg also exudes the grunginess of Dostoevsky novels and hipsters. Like fellow hipster-city, Seattle, St. Petersburg’s default autumn weather is chilly and gray. The air smells like rain, sea, cigarette smoke, and, occasionally, the warmth of sun on wet stone.

Built out of swampland in the early 18th century, the city center itself is like a giant piece of artwork. Theaters, palaces, museums, bookstores, and cafes are strung together along the contours of waterways, bridges, and avenues. Pastel palaces line the canals and granite embankments of the Neva, while elaborate footbridges connect the cobblestone streets. The golden spire of Peter and Paul Fortress rises above the choppy, indigo waters of the Neva River across from the massive columned facade of the Hermitage, the leafy statue-lined pathways of the Summer Garden, and the multi-colored onion domes of the Church of Our Savior on Spilled Blood (and no, the blood is not metaphorical –it’s Tsar Alexander II’s preserved in the back of the church on the collection of flagstones where he was assassinated in 1881).

But every time I have returned to St. Petersburg, no matter how many other places I go, I inevitably end up back on Nevsky Prospekt –the city’s bustling thoroughfare that stretches from Alexander Nevsky monastery at one bend in the Neva, up to the Admiralty next to Palace Square. When I think of Nevsky, it exists in all the seasons and time I have seen it in. At the far end, the rose-hued monastery is gorgeous and serene in the snows of my first winter in Russia in 2011. Here, next to the candle-lit, incense-infused church, next to the indoor mitten and honey market, and the fur-coat wearing babushka feeding the pigeons, is the final resting place of (as is inscribed over the gate) “The Masters of Art” –Dostoevsky, Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin, Balakirev, Mussorgsky, and yes, Cui, guarded by the cemetery cats and babushkas at the ticket booth.

Necropolis of the Masters of Art, 2011

Near the middle of Nevsky Prospekt, it is raining the chilly rain of an early November day in 2016. Past the St. Petersburg Philharmonic building and the road to the Russian Museum, the massive green copper dome and dark granite columns of Kazan Cathedral stand against the darkened sky, and water runs in rivulets down the cobblestones into the canal in front of Savior on Spilled Blood. People pour out of the metro station, hastily raising umbrellas as the sound of clattering trains and several accordion players chases them up the escalator. Across the canal from the metro, the art deco facade of Dom Knigi (House of Books) holds two huge stories of novels, souvenirs, and a cafe (much too expensive for an ordinary cup of tea) that overlooks a rainy Nevsky Prospekt packed with buses, cars, and bored tour operators holding iPhones up to their megaphones to effortlessly yell at passersby about the joy and excitement of taking a canal boat tour in the pouring rain. A couple streets over is a tiny hipster bookstore, complete with a study loft, window-facing cafe nook, two-story bookcases, and multi-colored Cubist portraits of Russian authors (and Jack Kerouac) on little stickers. I may never feel as cool again in my life as I did when I bought a couple of those. Ducking into a Stalovaya No. 1 (Cafeteria No. 1), people sit at small tables sipping hot tea in glasses and eating cabbage-filled pirozhkis, hearty plates of buckwheat kasha, and steaming bowls of mushroom or beet soup.

From the Dome of St. Isaac’s Cathedral, 2016

Bookstore/Cafe Podpisnie Izdaniya, 2016

Near the end of Nevsky Prospekt, it is unquestionably zolotaya os’en (golden autumn) -the most glorious of fall days when the sun warms your skin and illuminates the reds, oranges, and yellows of falling leaves, and a cool breeze shifts the clouds and blows the fresh smell of trees and sea through the city. Just before the Admiralty, the cobblestones curve under the giant yellow arches of a government building-turned-art museum, and onto Palace Square. Beautifully lit with the morning sun, the incredibly blue sky and the Alexander Column are reflected in the puddles and pools of yesterday’s rain. Across the Square, inside the Hermitage’s courtyard, the line is already assembled for the 10am opening. On that day, I waited in line as leaves fell and fountains gurgled and sparkled in the morning sunlight.

Arches to Palace Square, 2016

Arches on Palace Square, 2016

Nights at the Opera

March 1926

We had gone to the Opera the very day we arrived in Leningrad. The programme consisted of Boris Godunov. The brilliantly lit hall was crowded with men and women wearing overalls and dark clothes. Later on, we saw Prokoviev’s Love for Three Oranges and Russlan and Ludmilla, a prodigious work by the great precursor Glinka which is unfortunately never given outside of Russia. (My Happy Life 143)

October 2016

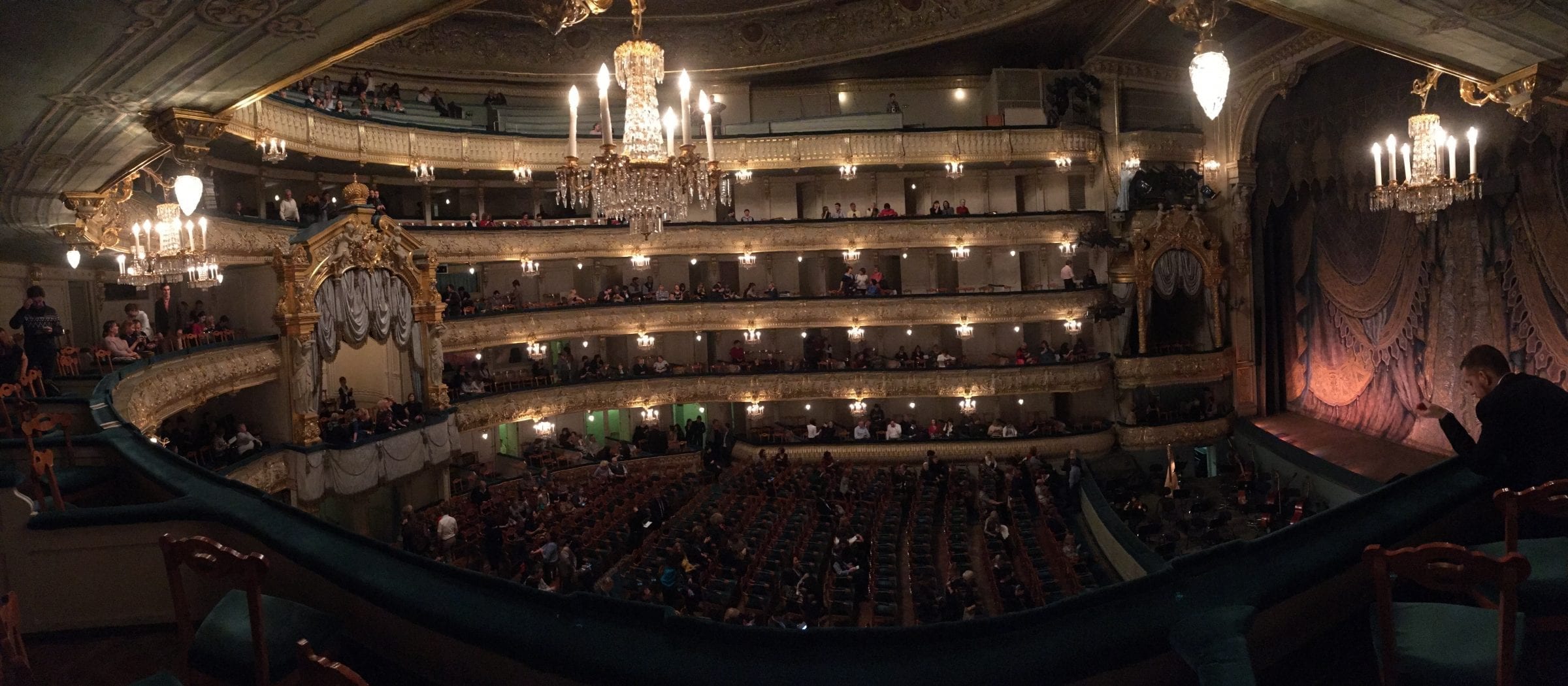

A little over 90 years after Milhaud enjoyed these performances, I dashed through a cold October rain into the lobby of the Mariinsky Theater, known to Milhaud as the Leningrad State Theater of Opera and Ballet. The charming 19th-century pale green and white walls of the lobby, the teal velvet seats, gold balconies, and the luxurious burgundy, bronze, and silver-layered stage curtain all glowed and sparkled in the light of hundreds of electric candles and chandeliers. But no one was in overalls; dressed to the nines, opera-goers milled around the coat-checks, mirrored hallways, carpeted staircases, and cafés selling wine and caviar. But despite the opulence, tickets remain relatively cheap, especially for foreigners and those not determined to sit right behind the pit orchestra. Where else in the world could you pay the equivalent of 23 dollars and sit next to the tsar’s box to see a world-class opera in a world-class theater?

I came to see Eugene Onegin -Tchaikovsky’s masterful musical interpretation of Alexander Pushkin’s classic novel-in-verse about love, jealousy, youth, coming of age, and superfluous men. Having researched and listened to the opera several times, I could hardly contain my excitement. When the lights dimmed in the theater, a spotlight illuminated an old man sitting in a box to stage left. A woman introduced this retired opera singer who fought bravely during World War II, dedicating the performance to him, and the hall rang with most warm and enthusiastic applause.

As amazing as Tchaikovsky sounds through earbuds on YouTube, nothing can replace the feeling of sitting in the darkness of a theater with over a thousand other people, listening as the silence is broken by the opening strains of the overture, watching as the stage transforms into a dark, snowy morning for Lensky’s soul-soaring aria, and feeling your heart simultaneously squeeze and expand as orchestral interludes swell to fill the theater in their full glory of layered and shifting harmonies, rich string timbres, searing brass crescendos, and sheer volume.

Going to School

March 1926

One morning the official from the Ministry of Fine Arts, who asked me each day what I would like to do, proposed that I should choose between a visit to a factory, a hospital, or a school. No doubt he was disappointed to hear that I was no more interested in visiting a factory or a hospital in the U.S.S.R. than I should have been in my own country, but I said I should be glad to see a school. The children greeted us by singing the Marseillaise and the Internationale, and to our great astonishment, we found every classroom adorned with banners bearing such inscriptions as ‘Long live the Commune!’ and a huge portrait of Louise Michel. It was customary to surround the pupils with objects illustrating the period of history which they were studying, and for the little Russians, Louise Michel was a legendary figure. In the school entrance there was a wall newspaper, edited and illustrated by the children, commenting on school business and the main political events. (My Happy Life 145-6)

September 2016

After several weeks of trying to find a Veliky Novgorod orchestra I could play in, I was promised that the Arensky School of Music would be happy to have me. Excited for the first rehearsal, I found my way to the school, tucked into a courtyard in the center of the city. Hanging my coat downstairs, I made my way up to the rehearsal room, and was a bit surprised to find that all of the other violinists and cellists were about half my age and my height. Turned out, “orchestra,” in this case, meant a string orchestra ages 7 to 16-ish. Instantly, I was bombarded by small children who wanted to talk to the American.

“How old are you?” a 13-ish year-old girl asked me in Russian.

“20,” I said.

Immediately, a 7-ish year-old boy piped up: “Are you pregnant?”

“No!?” (Incidentally, this wouldn’t be the last time I was asked by a kid if I was pregnant after telling them how old I was.)

Another 7 year-old boy sidled up to me. “Ni-ice tu meet iyu,” he said tentatively in English.

“Nice to meet you too!” I replied in Russian.

Looking around in confusion, he said in Russian, half to himself, half to anyone who was listening: “But I thought they speak English in America?”

On his way out the door, the first boy took this opportunity to approach me again. “I like cheese,” he declared in English, smiling satisfactorily at this complete sentence.

“You do? I like cheese too.”

Eying this exchange from across the room, the orchestra teacher yelled: “Yaroslav! Leave!”

Another young girl tries to talk to me in Russian before she is shooed out of the room so the rehearsal can finally start.

Wanting to practice their English, the teacher asked me to introduce myself in English. I did so, slowly, as a semi-circle of young string players listened carefully from behind their music stands. After the first sentence, there was a collective “ohhh,” and then fervent whispering to each other as they tried to translate my introductory remarks.

The teacher asked me what repertoire I had played recently. Hearing my answer (Sibelius), her eyebrow went up and glanced at the staff pianist. “Well, you may be a bit beyond this class.”

I stayed anyway. It was a relief to be playing again at any kind of music school.

After rehearsal, the teacher came up to me and asked if I would stay and help them for the next couple months. How could I refuse? So, what started out as a one-time visit, ended up being 3 months of weekly rehearsals, 2 concerts, 1 birthday party, and one of the best experiences of my time in Veliky Novgorod.

Time with Shostakovich

March 1926

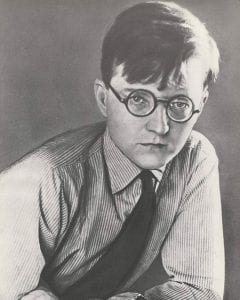

… a young man with dreamy eyes hidden behind enormous spectacles, came to show me a symphony which, in spite of its rather conventional form and construction, betrayed genuine gifts, and even had a certain quality of greatness, if it is remembered that its composer Shostakovich was only eighteen at the time and still a pupil at the [Leningrad] Conservatoire. (My Happy Life 144-45)

After Shostakovich’s First Symphony was successfully premiered in Leningrad on 12 May 1926, and subsequently performanced in Europe and America, Milhaud sent Shostakovich a congratulatory note.1 But Milhaud wasn’t the only foreign composer that Shostakovich played his music for in the 1920s. Shostakovich also played his trio for Franz Schreker in October 1925, played his First Symphony for Bruno Walter in January 1927, met Alban Berg in June 1927, and met Honegger in 1928 while Honegger was visiting Russia.2

Blockade of Leningrad Memorial-Monument, 2016

October 2016

Blockade of Leningrad Memorial-Monument, 2016

On a gray and chilly day in October, I visited the monument commemorating the Blockade of Leningrad. Over 1 million people died as a result of Nazi siege, which lasted from September 8 1941 to January 27 1944. Now, an enormous obelisk rises out of a subterranean circle lined with polished black metal carved with gold letters, and lit by flaming torches. Two rows of larger-than-life soldiers, workers, mothers, and children surged out from the obelisk. Descending into the sunken circle behind the base of the obelisk, the silence I expected to hear was broken by the dark, opening chords of Rachmaninov’s second piano concerto. A young couple placed flowers at the base of the statue of suffering figures in the middle of the circle. Music continued to reverberate around the ring of polished stone suspended above concrete walls.

Near the base of the obelisk, a wooden door opened into an underground room that descended down a wide, dark staircase into the vast hall of the memorial-museum of the Blockade. Red and gold Soviet mosaics sparkled at opposite ends of the hall, representing war and victory. Rachmaninov was replaced by the constant ticking of of a metronome and intermittent bursts of a familiar Soviet melody –the sounds of Leningrad’s wartime radio when they had nothing else left to play. Unlike most museums, the artifacts were laid out in glass-topped, stone cases. Looking at them from above, I got the strange and eerie feeling that I was peering into a time capsule or a coffin.

One case caught my eye. The plaque read: “In Leningrad under siege, during these incredibly difficult times, three institutes of higher education, thirty nine schools, three theatres and twenty cinemas functioned. Three daily newspapers were published; radio broadcasting continued; writers, poets, artists and composers continued their creative activities; and the Soviet scientific community successfully found solutions to assist in the defense of the city and the country.”

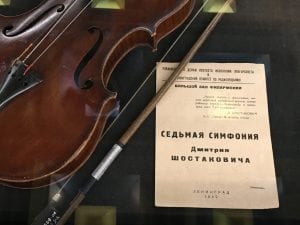

Violin and Program, Blockade of Leningrad Memorial-Museum, 2016

A violin with barely three strings attached lay next to a program of the Leningrad premiere of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony. Incredibly, the symphony’s Leningrad premiere was performed by starving Leningrad musicians in the Large Hall of the Philharmonia on August 9, 1942. Milhaud’s works were also played in this hall when he was in Leningrad in 1926. Looking closer at the program, I saw what was printed at the top of the page:

“Нашей борьбе с фашизмом, нашей грядущей победе над врагом, моему родному городу –Ленинграду я посвящаю свою 7-ую симфонию.” Д. Шостакович

“I dedicate my 7th Symphony to our fight against fascism, our coming victory over the enemy, to my native city of Leningrad.” D. Shostakovich

The metronome continued to tick in the darkened hall.

References

Fanning, David. “Paths to the First Symphony.” In The Cambridge Companion to Shostakovich, edited by Pauline Fairclough and David Fanning, 70-94. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Fay, Laurel E. Shostakovich: A Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Milhaud, Darius. My Happy Life, trans. Donald Evans, George Hall, and Christopher Palmer. London: Boyars, 1995.

You must be logged in to post a comment.