Mapping the Tours of the Fisk Jubilee Singers from 1871 to 1881

Introduction

What is this map?

This map shows the tours of the Fisk Jubilee Singers between 1871 and 1880. It is designed to show an overview of their tours, rather than details about each performance.

How to use this map

Click on a specific point to see more information about the location. If you zoom in to look at a particular city, click on the arrow in the top right hand side of the pop-up to view other performances in that area. Be sure to click in the center of the point so that you can view all of the concerts in that location.

Analysis

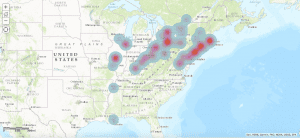

This map is important to this research for several reasons. First, notice especially in the Northeast United States, there is significant evidence of clearly defined tours. For instance, there is a line of concerts that follows the Atlantic coast, and another that goes along the Canadian border. It is important to keep in mind that this map is based on a specific source list, however, so these tours could be defined by the scholars who compiled these works. Perhaps more importantly, however, this map demonstrates that Gospel music was heard in a wide variety of cities as far back as 1871. This is the beginnings of the spread of the Spiritual tradition to a large scope of audiences, including white audiences who were not familiar with the music.

What is this map?

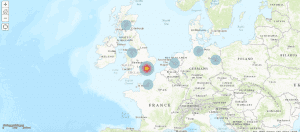

This map shows the concentration of the Fisk Jubilee Singer’s concerts in different areas across the United States and Europe using a heat map feature. It is a static map rather than an interactive map, meaning you can’t click on any points on the map or zoom in and out. It is designed this way to show the concentration of concerts in smaller cities.

How to use this map

Compare the concentration of concerts in the map of the United States (above) and the map of Europe (below). Click on the images to see a larger version of each map.

Analysis

These maps show us the cities where the Fisk Jubilee Singers performed the most. It is evident that the group’s performances were much more concentrated in Northern cities of the United States. This is interesting as Fisk University itself is located in Tennessee. We could attribute this trend to the political climate after the emancipation of slaves, keeping in mind that this map represents what my sources recorded. On the European side, we can see that there was a very high concentration of performances in London, and the rest of England. So we may ask, was this pattern the result of the popularity of the music itself, or of the patronage of wealthy nobles the group encountered there?

Methodology

Sources

I relied primarily on books, dissertations, and articles for my research. See my bibliography at the bottom of the page for a more detailed list. For some books, such as Andrew Ward’s Dark Midnight When I Rise: the story of the Jubilee Singers, who introduced the world to the music of Black America, I read through the prose and recorded whatever concerts were mentioned. For other sources, like dissertations, I went through the bibliographies and recorded each reference to newspaper articles about the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Although the date of the article didn’t always correspond to the exact concert date, it was likely that the concert took place around that date, in the city of the publication. Unfortunately, I was not able to get through all of the sources as thoroughly as I would have liked, so there are likely gaps in the data.

Data Gathering

When I originally undertook this project, I planned to compile detailed information about the tours of the Fisk Jubilee Singers in The United States, Europe, and even Australia. I soon discovered that it was unrealistic to try to compile this much information in the time I had. So, I limited myself to the year range of 1871 to 1881. This was a logical break based on the research I had already completed, as the group disbanded temporarily in 1880. I compiled as many performances as I could into a Google Spreadsheet, available to view here. You will notice that some of the concerts have detailed descriptions, while others simply have locations and dates. This is a result of my decision to compile more data with less detail for the purposes of creating maps with as many points as possible.

When I consulted Doug Seroff’s article”‘A Voice in the Wilderness’: The Fisk Jubilee Singers’ civil rights tours of 1879-1882,” I recorded dates of concerts based on a fairly extensive list of newspaper articles about Fisk Jubilee concerts in his bibliography. I determined that, for the purposes of my project, it was enough to have a city and an approximate date to include a concert in my database. Some of the data entries include venue names, but I soon decided only to geolocate cities, because the Fisk Jubilee Singers often performed in churches and small concert halls. It seemed too time consuming to find these smaller venues, and I was more interested in the region they performed in, rather than the specific venue.

Mapmaking

I made two maps using the database I compiled for this project. The first is a simple interactive map, including all of the points corresponding to each concert I found. The second is a static heat map showing the concentration of performances across different regions in The United States and Europe.

I purposely made these maps simple, because my goal was to display an overview of the scope of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, rather than a detailed description of their concerts. I also did not include a lot of information in the pop-up boxes so that the viewer would focus on the patterns the map reveals more than the individual points.

Going Forward

I had many dreams going into this project that were not realized. For instance, I would have loved to create a map with two layers comparing the Fisk Jubilee Singer’s concerts and the scope of their recordings. Brooks and Spottswood posit that white audiences were more likely to buy recordings than to see the singers in concert, which they suggest implies a distancing of white audiences from a first-hand experience of the music. This could be a fascinating map to explore in the future. Additionally, the database I have created could easily be turned into a story map, which would allow viewers to have a richer experience of the tours of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. My hope is that I, or some eager future researcher, can undertake these deeper questions.

Bibliography

Brooks, Tim, and Spottswood, Richard K. Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890-1919. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2010.

Graham, Sandra Jean. “The Fisk Jubilee Singers and the concert spiritual: The beginnings of an American tradition.” PhD diss, New York University, 2001.

Pike, Gustavus D. The Jubilee Singers: and their campaign for twenty thousand dollars. Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1873.

Seroff, Doug. “‘A Voice in the Wilderness’: The Fisk Jubilee Singers’ civil rights tours of 1879-1882.” Popular Music and Society, 25. (2001): 131-177

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History. New York: Norton, 1971.

Ward, Andrew. Dark Midnight When I Rise: the story of the Jubilee Singers, who introduced the world to the music of Black America. New York : Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2000.

You must be logged in to post a comment.