Francis Johnson’s Tours

Francis Johnson was a musician, bandleader and composer in antebellum America. A Black man in an institutionally racist

society that was sometimes hostile towards him, Johnson nevertheless found great success as a result of his skill in performing

and composing. He was widely acclaimed for his daring innovation within European musical genres, and he popularized

new styles in America while pushing the boundaries of art music.

The fact that Francis Johnson was able to find any success at all in early nineteenth century America as a Black man intrigued us.

We wanted to know more about the circumstances that facilitated his success. There is an argument that Johnson succeeded

because he worked in a progressive atmosphere that did not exist outside of Philadelphia and because his music took advantage

of traditions of high society.1 However, the widespread success he found across the country and even in Europe using a variety

of musical genres, as well as the degree to which he innovated within these spaces, belies the idea that Philadelphia was a rare

oasis of tolerance and safety, as he managed to succeed nearly everywhere he traveled.

Knowing that Johnson traveled widely around the East Coast and Midwest regions of the United States and also toured in

England and France, we wanted to look at the extent of his travels and see if there were any patterns. We were also interested

in the types of events he performed at. We looked at concerts given specifically by Johnson and his band in contrast to other

events such as art exhibitions, balls and parades. We found that in addition to touring and giving many concerts in Philadelphia

and the surrounding area, the band also engaged in other types of events, revealing that some of their income came

from what could be considered “odd jobs.”

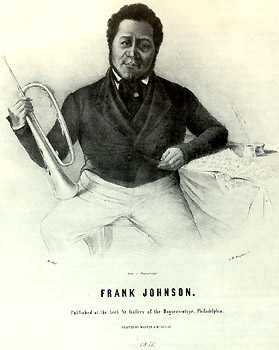

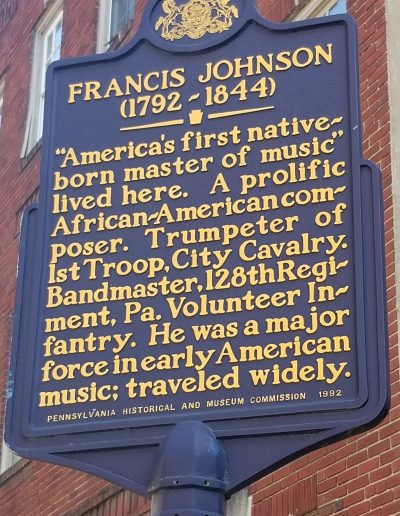

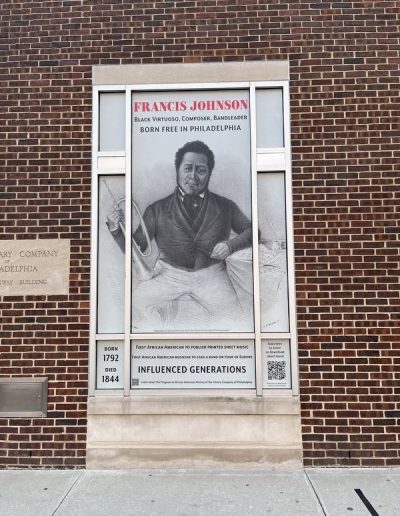

Francis Johnson Historical Marker

at 1314 Locust St, Philadelphia, PA. Photograph By Devry Becker Jones.

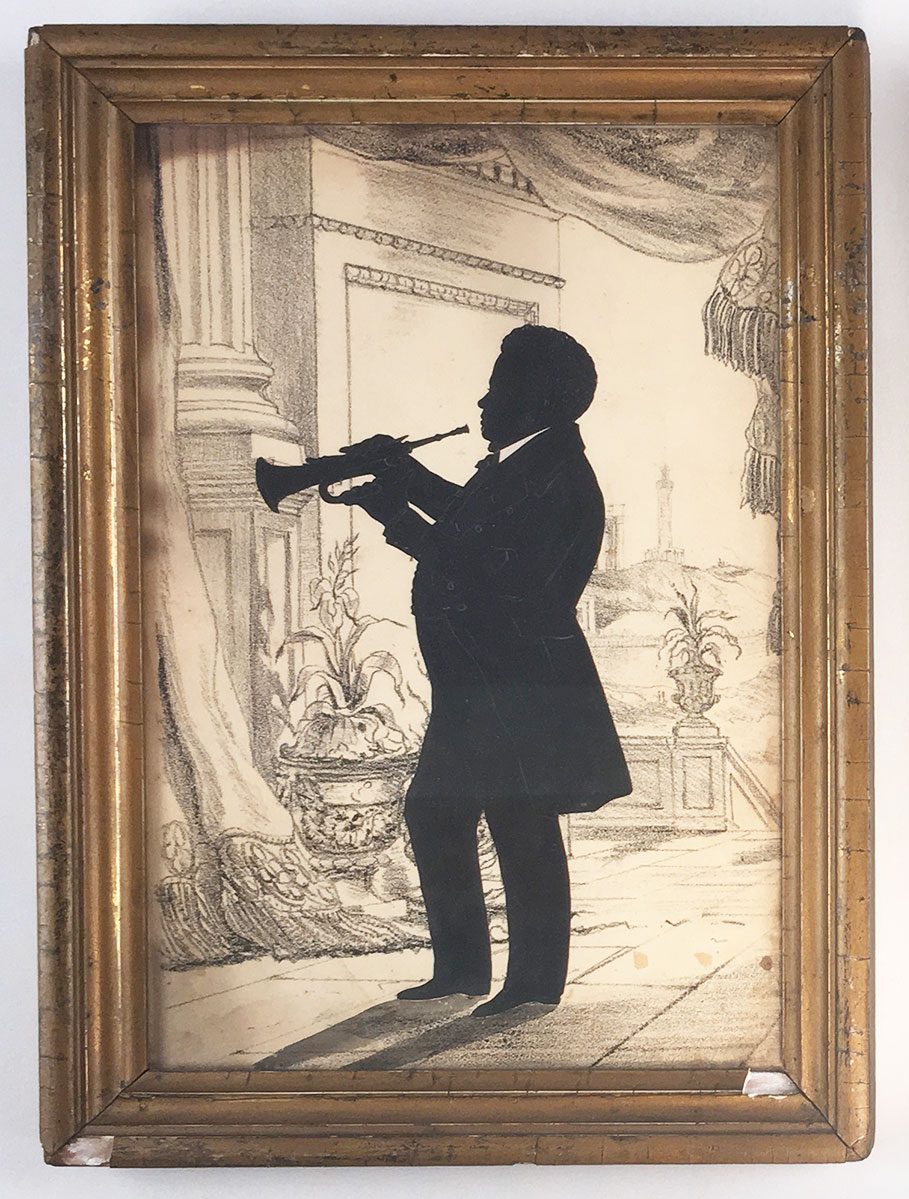

Illustration of a Keyed Bugle

“Corps d’Afrique, 1864” by Fritz Kredel in the book “Soldiers of the American Army.”

Literature Review

We benefited from reviewing a mix of the secondary sources that have been written on Johnson and primary sources either about Johnson and his band or from Johnson himself. There are a number of scholarly works on Johnson’s life and career, which mostly helped us collect biographical information and contextualize Johnson’s career within the racial and musical environment of antebellum America. The literature also provides a number of different perspectives on what exactly led to Johnson’s success. Richard Griscom points out that much of Johnson’s music was intended simply to appeal to his audience, rather than to be innovative or new.2 On the other hand, Hayden Kramer asserts that Johnson was in fact striving to be innovative while also pointing out that Johnson was not necessarily trying to be the “first” anything, but rather trying to set himself apart from his contemporaries.3 Both of these authors cite economic considerations as reasons for Johnson’s success, but take different positions on the uniqueness of his music. These perspectives were useful in helping us direct our research, as these researchers have already posed questions for us to think about.

Research Revelations

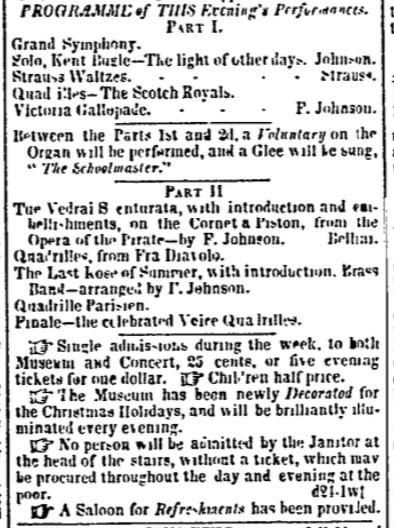

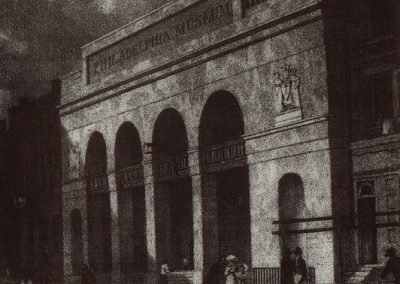

We searched various databases, including America’s Historical Newspapers, to find primary sources, including newspaper articles (see clipping above) and advertisements as well as posters, that provided information about Johnson’s band and their travels. These sources proved to be extremely valuable in helping us pin down exactly when and where many of his performances took place, and we compiled them into a spreadsheet. The spreadsheet mostly documents performances by Johnson’s band, although it also includes instances of his compositions being written and pivotal life events. For each source, we included an “Event Description,” specified its “Type” (performance, composition, or life event) and included “Parties involved,” in addition to connecting each event and its significance to the date and geographic location.

The primary sources we uncovered further revealed how Johnson advertised his band’s

performances as well as the way others wrote about them. For instance, several advertisements are not for any particular performance, but simply ask the public to continue to patronize Johnson and attend his concerts.4 The energy with which Johnson pursued publicity through advertising probably contributed to the success of his band, and these advertisements help tell the story of his travels.

Many of these sources describe recent performances as proof of Johnson’s success. For example, one contemporary newspaper article describes how Johnson “has been delighting the amateurs of our sister city, Pittsburgh, with his delicious music. He has drawn full houses, and has been treated by the citizens in generally the most kind and cordial manner.”5 However, the same article goes on to describe how a mob gathered outside one of his concerts and “by their hooting and yelling did what they could to mar” the experience, and afterwards attacked the performers with racial slurs and thrown projectiles. The author condemns these “mobocrats” and stresses that “every well-disposed citizen deeply regretted the disgrace thus brought upon our city,” indicating that such reactions were in the minority. Articles like these reveal the personal opinions of members of the public on Johnson’s music, as well as making social commentary. One describes Johnson as a tradesman of sorts, reflecting the fact that composing and performing in Johnson’s time meant relying in large part on public support, while another author remarks that abolitionists must not be “sincere in their professions,” or else his concerts would be better attended. This comment reveals that his concerts were not always successful and indicates that at least one listener believed Johnson’s racial identity to be intimately connected with his success.

A Black Bandmaster in Antebellum America

Although there are records of racist reactions to his performances, leading to a riot in at least one case, we were unable to find any evidence of such reactions in Philadelphia, adding to the perception that the liberal atmosphere of the city lent itself at least to some extent to the success of a Black man in the early nineteenth century.11 The question remains: exactly how much of an impact did racism have on Johnson’s life and success? Although he was undeniably successful in Philadelphia, it is not clear that his experiences there were free of racism. He certainly faced racism in other places, and encountered not only racist audiences (and at least one violent mob) but also the hostility of racist law enforcement.12

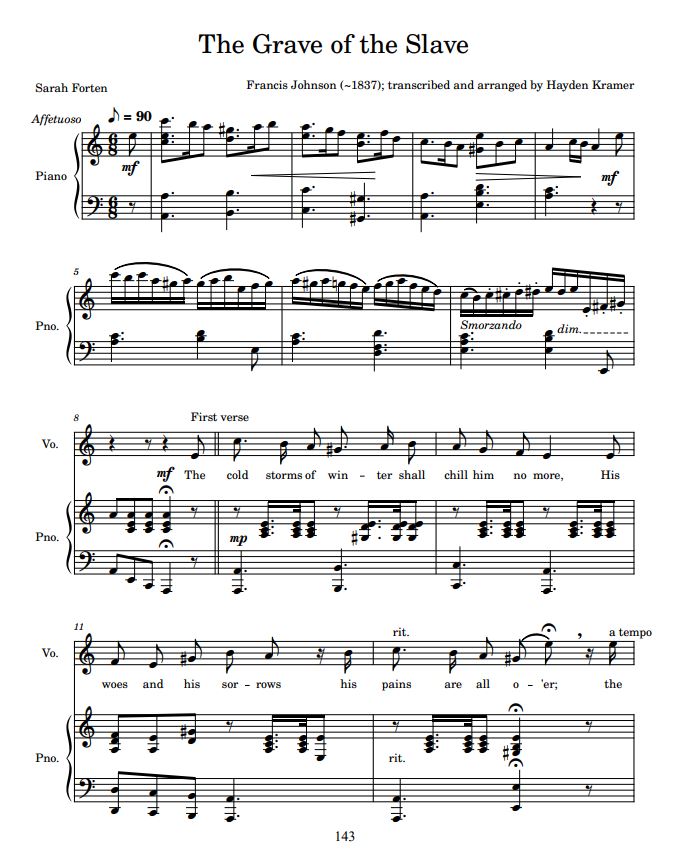

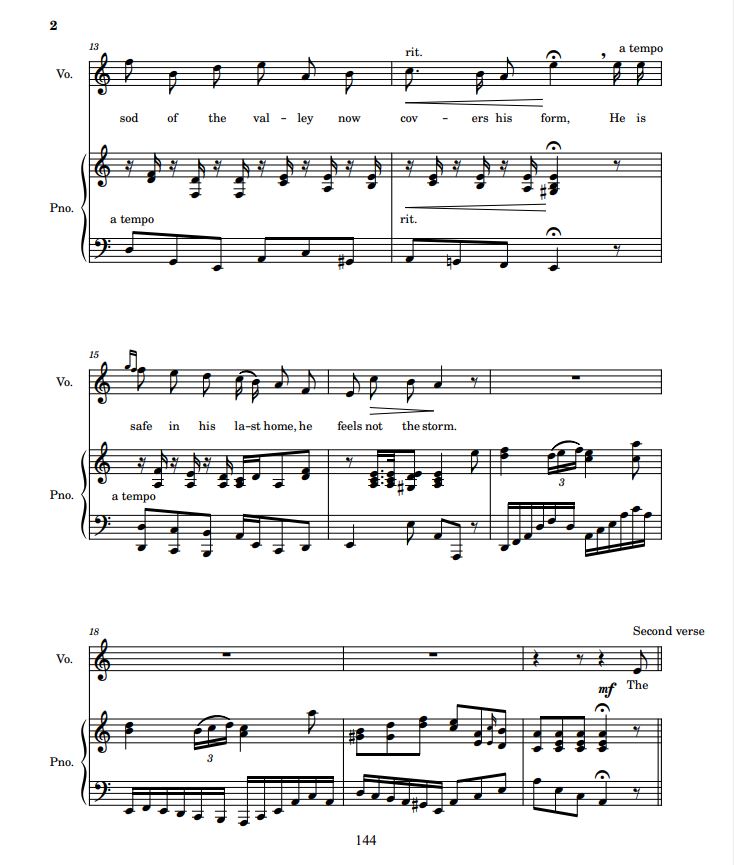

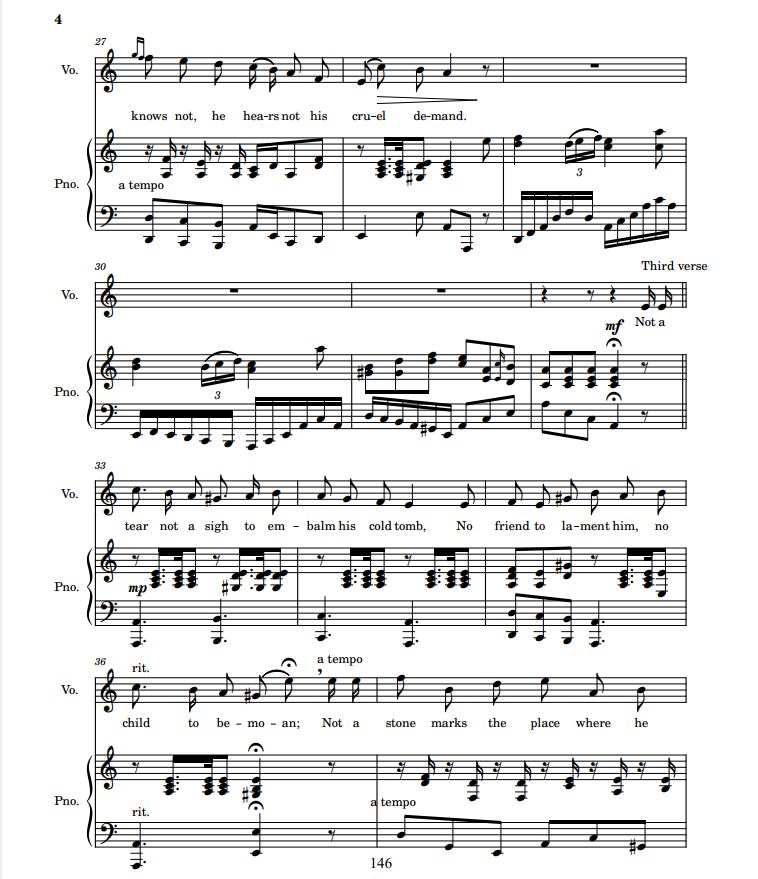

Other primary sources do not mention violence or hostility, but simply identify Johnson as a Black man, indicating that this fact was widely known and had some significance to his audiences.13 Johnson was born free and grew up with relative privilege, and his music was directed towards a white middle class audience. However, he was not afraid to rebel against mainstream American ideas in order to confront the racism that he and other Black Americans faced. He composed “Grave of the Slave” from Sarah Forten’s abolitionist poem and “Recognition March on the Independence of Hayti,” which was “composed expressly for the occasion and dedicated to President J. P. Boyer by his humble servant with every sentiment of respect”, making Johnson the first composer writing for this audience to portray slavery in a negative light.14 This indicates that despite his privilege and that of his audience, Johnson identified with enslaved Black people, perhaps seeing himself as a spokesperson for those less fortunate. Still, Johnson only touched upon the subject of abolitionism in a few of his compositions, and most contemporary accounts don’t consider this fact important enough to mention. Whatever benefits Johnson may have gained from working in Philadelphia, his willingness to confront racism and the effects it had on him show that Johnson’s enormous success despite these challenges was because of his skill and his appeal to a wide range of audiences.

Transcription of “Grave of the Slave” (c. 1837)

Johnson’s Travels Abroad

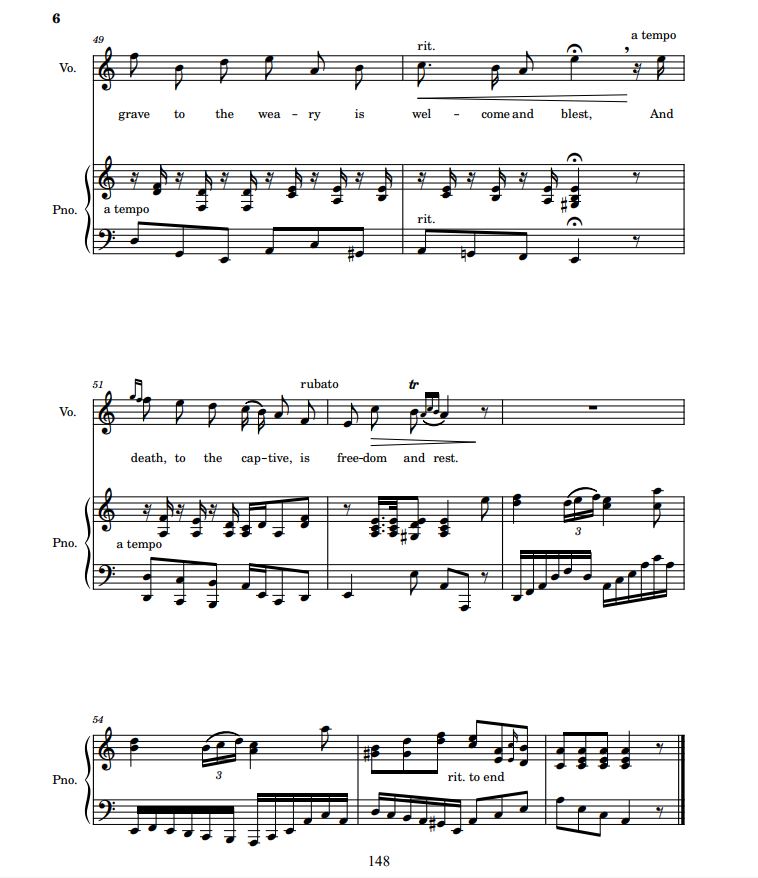

In addition to exploring Johnson’s tours throughout the United States, we also wanted to focus on Johnson’s travels abroad. We know that his success was not limited to America and that his experiences in Europe served as inspiration for his later music. Johnson was the first bandleader from the United States of any race to tour in Europe.15 This fact is interesting in several ways: it indicates that he was popular and financially successful enough in America to have the resources and level of organization to go abroad, and that knowledge of his music had reached European audiences who took interest in it. Unfortunately, we were unable to find sources detailing the majority of his concerts on this tour, making it difficult to map it in the same way as we could for his domestic concerts. Therefore, further research may be needed. We do know that the tour was very successful, further proving the worth of his music for British and French audiences as well as American ones. The tour also greatly influenced Johnson and his work. He was inspired by the promenade concerts of French composer Philippe Musard, which he studied extensively, and after his return he began to advertise his concerts as “soirées”, “grand soirées musicales”, or “grand promenade concerts.”16 He also began to program the music of European composers, as well as compose new music in European styles, revealing his admiration for the art music scene in Europe.17 His musical innovation also helped to inspire further development of American art music.

Small Concerts at Almack’s Assembly Rooms in 1838

Located on King Street, St. James, London, England – Illustration from the Museum of London (1800)

Concert for Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle in 1838

Windsor Castle, Windsor, England – Photograph by Arthur James Melhuish (1854-56).

Example of a “Parisian View of a Concert Musard”

Francis Johnson may have attended (but was surely inspired by) a Concert Musard during his European tours, and modelled his following concerts after them. Illustration from Le Bibliothèque nationale de Paris.

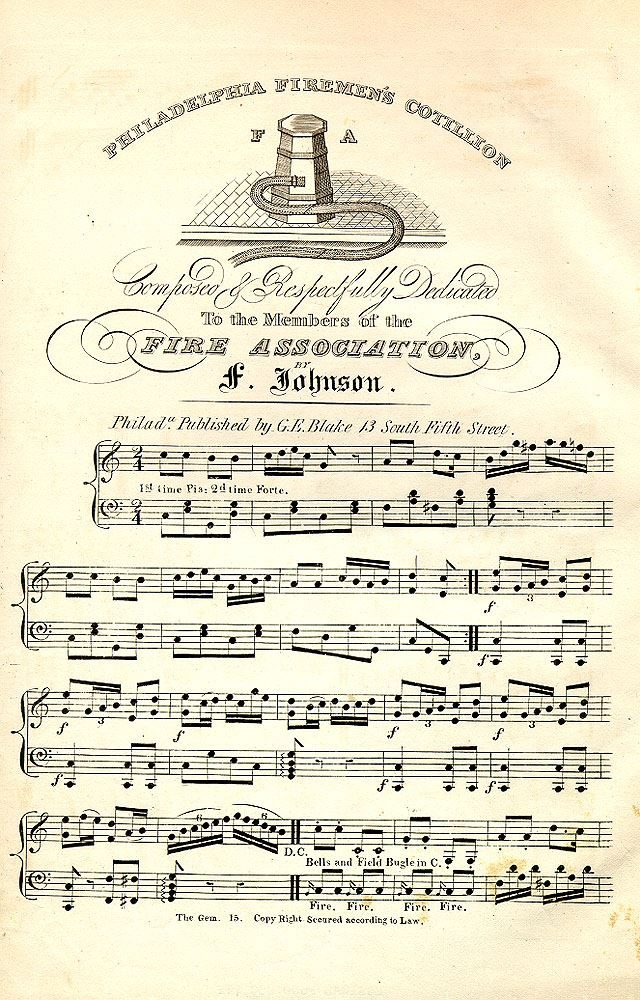

An Architect of American Music

Johnson’s tendency for musical innovation was a major factor in his success, and many of his works—both before and after his European tour—display a compelling amount of creativity and versatility. Johnson seemed to embrace the classical sphere and style of composition through the multitude of cotillions that he composed and performed throughout his life, as well as his later, European-style “soiree” and “promenade” concerts. While Johnson championed the standard set by European composers, his willingness to challenge the norms of European art music reveals a duality in his composition.

With the wealth of a “great variety of music imported from London and Paris” after his band’s 1838 European tour, Johnson would program waltzes by Johann Strauss alongside pieces by Daniel-François-Esprit Auber and Gioacchino Rossini into his concerts.18 Yet the “promenade” format of performance that he brought stateside for the Christmas season would eventually morph into something newly American—the classical “pops” style.19 In a “Grand Soiree Musicale” benefit, Johnson’s programme additionally included more contemporary pieces, including Henry Russell’s 1837 “Woodman Spare That Tree!,” early versions of the national anthem, and “Yankee Doodle.” Other American musical styles that Johnson is considered a forefather of include jazz, ragtime, and military music, positioning him at “the crux of the nation’s sound.”20 His incorporation of quadrilles into the aforementioned promenade concerts—possibly their first introduction in the United States—came from the same European inspiration as well, but he still chose to go against the grain. Traditionally, quadrilles were divided into five parts that were referred to by generic labels.21 Johnson followed this compositional style and form, but created three unique titles for his Voice Quadrilles and all five titles for The Citizen’s Quadrilles. In Johnson’s 1840 Voice Quadrilles, he made further strides in crafting original musical techniques for his time, where the band members were instructed to sing in some sections and to vocalize “ha-ha” in a genre that had previously been purely instrumental.22 Some scholars further posit that William Bradbury, the composer behind pieces such as “Jesus Loves Me,” wrote choral works inspired by Johnson’s Voice Quadrilles.23 Even in earlier compositions such as his Sleigh Waltzes and Battle of N’Orleans, both dating from the 1820s, wood blocks were used in the place of the snare drum in an attempt to simulate the sound of the “galloping of horses.”24

Alongside his innovation within distinctly European styles, Johnson would often compose patriotic marches and quick-steps dedicated to the leaders of military bands that he worked alongside and pair them with the European arrangements he utilized in his “promenade” programs.25 He also brought white musicians into his band, thereby leading some of the first interracial musical performances in the United States.26 Eileen Southern further claimed that Johnson was collaborating with white composers in Philadelphia, even at the beginning of his career.27 Despite the depth of the inspiration he drew from European standards, some have labeled his “well-documented propensity for improvisation” as “proto-jazz”.28 It is important to acknowledge that this is a racialized comparison that may have been an attempt to delegitimize Johnson’s demonstrated talent and broader impact on music history, as white composers had been employing improvisatory techniques for centuries prior and have not been labeled as proto-jazz.

Conclusions/Further Research Directions

Johnson’s popularity in a racist society benefited to some extent from the progressive attitudes of many citizens of Philadelphia, as well as Johnson’s own privilege as a free man. His choice to cater to popular tastes also played a role. However, his success was largely due to his own talents and initiative. Much of his music was innovative and daring both in its subject matter and in the techniques he employed. The vigor with which he advertised his band’s services as well as the frequency and variety of their performances helped cement their reputation in Philadelphia and across the country. In addition, he brought attention to European musical genres in America while also pushing the boundaries of these often restrictive genres.

While our research reveals many of the factors behind Johnson’s success, it also leaves us with questions, providing directions for further research. Perhaps the biggest unanswered question is why Johnson is not more well known today, given his incredible popularity during his own lifetime. Even leaving aside his musical talent and creativity, Johnson’s success as a Black man in the Antebellum Period was an achievement in its own right, and he stands an early example of a person of color who found popularity and fame within an institutionally racist society. However, his name has been largely forgotten.

A variety of factors may be responsible for this, and comparing Johnson to any other Black musicians that may have been performing around the same time could help provide more context into his success. Another Black musician of the Antebellum Period who could be worth comparing Johnson’s opportunities and career outcomes to is—ironically enough—Frank Johnson (c. 1789-1871), a North Carolinian fiddler who has also been considered the “most important African-American musician of the nineteenth century.”29 It’s critical to admit the existence of a homonymous Frank Johnson, another Antebellum Era musician who’s often mistaken for and overlooked by researchers in favor of the Francis Johnson we’ve studied (he was born a slave in the South, which has likely obscured the record). This epitomizes how we only scratched the surface in our research on a singular pivotal Black musician. Additionally, we believe developing more context about how Francis Johnson’s career looked relative to white bandmasters and composers of his era would be useful.

An increasing separation between art music and popular music occurred towards the end of the nineteenth century in America.30 This may have played a role in Johnson’s reception by drawing the attention of later generations away from Johnson, whose repertoire involved a wide range of genres. Unfortunately, because Johnson’s estate was divided up after his death, many of his original manuscripts remain missing and most are not available in their original, full band instrumentation, making it difficult to make his music accessible to the general public in any meaningful way.31 This was especially apparent in our cataloguing of Johnson’s surviving music. Around half of his scores remain missing or unavailable to the public, and those that are available are primarily arranged for piano with missing cues for different band instruments. In addition, we need to know more about the negative experiences Johnson had, including mob violence, discrimination from law enforcement, and prejudice from audiences. Determining whether there were any patterns in these experiences and whether any of them occurred in Philadelphia could also help clarify how much of Johnson’s success was due to the liberal spirit he found in Philadelphia.

Additionally, locating more information and primary sources specifically addressing the nature of his European tour and performances abroad would greatly enrich a scholarly understanding of the profound effect they had on his music making. Due to time constraints and limitations within our team, we were not able to reach out to a scholar for direct consultation on Frank Johnson, but we know that Colin Roust, a professor of musicology at the University of Kansas, could be a valuable resource for gaining additional context on Johnson’s life and work.

Lastly, we would like to thank Professor Epstein for his guidance in navigating the ebbs and flows of research and offering support to our team throughout the semester. We would also like to acknowledge the assistance of Sara Dale from IT in helping us create our maps in ArcGIS and providing general insights on mapping and St. Olaf’s own Music Librarian Karen Olson, who also provided direction on researching within the St. Olaf and Carleton Library catalog.

About the Team

Shelsea Johnson (she/her) is a senior majoring in Psychology and Music with a Race & Ethnic Studies concentration. Francis Johnson’s unique sociocultural position in Philadelphia and the antebellum world was a major source of intrigue, and continued to serve as her driving motivation. With little previous research experience with archival research of this calibre, this project was a great opportunity to develop and hone these skills. In our research on Johnson’s composition catalogue and performances, the amount of lost music and historical records weighed heavily—but Johnson’s overwhelming artistry and ingenuity still shone through clearly.

Calvin Reyes (he/him) is a senior Music and Math major with a concentration in Statistics and Data Science. As a trumpet player, Francis Johnson seemed like an interesting topic because he was also a trumpet player. After reading more about him, Calvin was really impressed with his level of success given the institutionally racist society that he lived in. For Calvin, this project was a great way to shine light on a successful musician and composer that is almost completely forgotten in our current educational curriculum who had a great influence on not only music in America, but also American society.

Atle Wammer (he/him) is a junior majoring in Race & Ethnic Studies and Asian Studies with a Linguistics concentration. He was initially drawn to this topic due to curiosity about how a Black musician had become so successful in antebellum America but was practically unknown today, and really enjoyed the process of learning more about his story and uncovering the complex factors behind his success.

Davis Moore (he/him) is a senior History and Music major with a concentration in Environmental Studies. For Davis, this was his second experience working on a Musical Geography site after “Mapping Washington Conservatory Alumni in Black American Musical Life.” The project reinforced his sense of how archival research pulls one “back in time” through critical attention to fascinating historical figures. He particularly enjoyed exploring Antebellum Period music for the first time, as it connects to historical research he conducted in a previous class on African American sailors’ lives (interesting fact: musicians on ships in early US history were mostly men of color).

Footnotes

1 Richard Griscom, “Francis Johnson: Philadelphia Bandmaster and Composer,” University of Pennsylvania Almanac, February 14, 2012. https://almanac.upenn.edu/archive/volumes/v58/n22/bandmaster.html.

2 Ibid.

3 Kramer, Hayden James. “Six Works by Francis Johnson (1792–1844): A Snapshot of Early American Social Life.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2022, 70.

4 “Advertisement.” Public Ledger (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) VI, no. 79, December 28, 1838: [3]. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

5“Riot near Pittsburgh–Frank Johnson’s Band Mobbed. Correspondence of the N. Y. Tribune.” Albany Evening Journal (Albany, New York) 14, no. 4103, May 23, 1843: [2]. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

6 “From the National Gazette.” Southern Patriot (Charleston, South Carolina) XLVI, no. 7072, November 24, 1841: [2]. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers;”Frank Johnson in Boston.” Sun (Baltimore, Maryland) III, no. 135, October 22, 1838: [2]. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A11343008E4D07040%40EANX-11AE540ED60C16B8%402392670-11AE540EE23B6D80%401-11AE540F1E3CE7E0%40Frank%2BJohnson%2Bin%2BBoston.

7 Griscom, “Bandmaster and Composer.” https://almanac.upenn.edu/archive/volumes/v58/n22/bandmaster.html.

8 Earnest Lamb, “The Music of Francis Johnson and His Contemporaries: Early 19th-Century Black Composers. The Chestnut Brass Company and Friends, Tamara Brooks, Conductor. Music Masters 7029-2-C, 1990,” Journal of the Society for American Music 8, no. 2 (2014): 266–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752196314000133.

9 “Advertisement.” Public Ledger (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) VI, no. 79, December 28, 1838: [3]. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A12368904C6A6FB72%40EANX-1252394001F5D8A8%402392737-1252394025BC5EB0%402-12523940AE0D0448%40Advertisement; “Local Affairs.” Public Ledger (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) XVI, no. 28, October 26, 1843: [2]. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers.

10 Thomas J. Scharf and Westcott Thompson, History of Philadelphia, 1609-1884 (Philadelphia: L.H. Everts & Co, 1884), 1076.

11 Albany Evening Journal, “Riot Near Pittsburgh,” 2.

12 Ibid., 4; Griscom, “Bandmaster and Composer.” https://almanac.upenn.edu/archive/volumes/v58/n22/bandmaster.html.

13 “[Frank Johnson; St. Louis].” Boston Evening Transcript (Boston, Massachusetts) XIV, no. 3821, January 6, 1843: [2]. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A11A6DA052115FC68%40EANX-11AE205199C273B0%402394207-11AE2051AC9F0110%401-11AE20520E4F4CB0%40%255BFrank%2BJohnson%253B%2BSt.%2BLouis%255D: 2; “[Frank Johnson; Cincinnati].” Emancipator and Republican (Boston, Massachusetts) VIII, no. 4, May 25, 1843: 14. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A1148B187EE739DE8%40EANX-11ACD7CEE2EF34F0%402394346-11ACD7CEFB419DE0%401-11ACD7CF5FC21C98%40%255BFrank%2BJohnson%253B%2BCincinnati%255D.

14 Kramer, “Six Works,” 4, 70.

15 Ibid., 70.

16 Ralph T. Didgeon, “America’s Original Virtuoso: Francis Johnson,” Ovation, 02, 1989, 28-29. https://www.proquest.com/magazines/americas-original-virtuoso-francis-johnson/docview/220408641/se-2.

17 “Promenade Concerts A La Musard.” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) XXIII, no. 152, December 24, 1840: [2]. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A110C9BFA1F116650%40EANX-11F13A4A6AAFCBA0%402393464-11F13A4A9AF4AE38%401-11F13A4CAA2CA950%40Promenade%2BConcerts%2BA%2BLa%2BMusard”>https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A110C9BFA1F116650%40EANX-11F13A4A6AAFCBA0%402393464-11F13A4A9AF4AE38%401-11F13A4CAA2CA950%40Promenade%2BConcerts%2BA%2BLa%2BMusard.

18 Ibid.; “Advertisement.” Massachusetts Spy (Worcester, Massachusetts) 67, no. 41, October 10, 1838: [3]. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A10284A66F6BC7768%40EANX-1325E14D32A3EDA0%402392658-1324D924D15A0828%402-1395980667D6B3B1%40Advertisement.

19 Brian McCurdy, “Hidden Gems of the NLS Collection: Francis “Frank” Johnson,” Library of Congress, (2022).

20 “Library Company celebrates Philadelphian Francis Johnson, forefather of American music.” Philadelphia Tribune (Philadelphia, PA), Sep. 6, 2019; Small, Christopher, and Robert Walser. The Christopher Small Reader. Edited by Robert Walser. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2016. 70.

21 Andrew Lamb, “Quadrille,” Grove Music Online, 2001. Accessed 2022. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000022622.

22 Richard S.Newmann, Philadelphia Stories: People and Their Places in Early America, ed. Rodney Hessinger and Daniel K Richter, (United States: University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated, 2021): 234.

23 Juanita Karpf, “Populism with Religious Restraint: William B. Bradbury’s Esther, the Beautiful Queen,” Popular Music and Society 23, no. 1 (Spring, 1999): 1-29.

24 Francis Johnson, Sleigh Waltzes, ed. Lavern Wagner, Recent Researches in American Music, vol. 29. Middleton, WI: A-R Editions, Inc., 1998. https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cscore%7C881093; Kramer, “Six Works,” 119-120; “Advertisement.” Pittsfield Sun (Pittsfield, Massachusetts) XLIII, no. 2190, September 8, 1842: [3]. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A105F9E4894BE8C00%40EANX-10647C7783069EC9%402394087-10647C782F620B6A%402-10647C79C7B7F0C4%40Advertisement.

25 Newmann, Philadelphia Stories, 233.

26 McCurdy, “Hidden Gems.”

27 Kramer, “Six Works,” 11.

28 Eileen Southern, “Frank Johnson of Philadelphia and His Promenade Concerts,” The Black Perspective in Music 5, no. 1 (1977): 3–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/1214356.

29 John Jeremiah Sullivan, “Rhiannon Giddens and What Folk Music Means,” The New Yorker, May 13, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/05/20/rhiannon-giddens-and-what-folk-music-means.

30 Ralph P. Locke, “Music Lovers, Patrons, and the ‘Sacralization’ of Culture in America,” 19th-Century Music 17, no. 2 (1993): 149–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/746331.

You must be logged in to post a comment.