Last evening’s concert at the Théâtre de Champs-Elysées[1] proved to be a splendid evening of the highest quality of music and dancing, representative of the kind of work that the Parisian community has come to expect from the Ballets Russes dance troupe. This much-anticipated event included the return of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps, along with his Petrouchka and Manuel de Falla’s Le Tricorne, all choreographed by Léonide Massine and conducted by Ernest Ansermet.[2] It would be impossible to overstate the chaos at the Champs Elysées on the night of the first premier of Le Sacre only seven years ago,[3] and although the musical community has largely come to accept the piece as worthy of its prominent place in the concert repertoire, that premier concert, with its bizarre choreography and shocking music, was an outrage. The concert last night, however, has redeemed the piece, and the brilliant programming and choreographic changes all contributed to a performance that was simply sublime.

This concert showed that the Ballets Russes is fully capable of programming a brilliant program of ballets that work with one another to produce a cohesive performance experience. Whereas the 1913 premiere of Le Sacre included a nonsensical collection of works on its program,[4] the performance from last evening was accompanied by two other works of the same vein: Petrouchka, with its elements of Russian folk culture, and de Falla’s Le Tricorne, with its charming eighteenth-century Spanish influences.[5] All the shock of hearing Le Sacre du Printemps for the very first time alongside such a tonal masterpiece as Chopin’s Les Sylphides seemed to melt away as I listened to three works that made aural and visual sense together. I found that the elements of folk dance and costuming came alive in all three works, further highlighting the strengths of the Ballets Russes in transporting the audience member to places far outside the boundaries of Paris. Perhaps it was that I have been desensitized to the musical shock of Le Sacre after having heard it so many times in the past years,[6] but the experience of hearing it in this new context was much more pleasant than ever before. As a result of this genius in programming, I was able to appreciate the innovation of Stravinsky’s score, which held even greater weight for me as I aurally compared it to the other two pieces on the program. The music certainly stands alone as one of the greatest masterworks of our time, and I found that its revolutionary approaches to tonality and rhythmic complexity were highlighted appropriately in the performance.

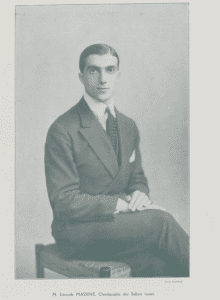

Photograph of Massine, the choreographer of the 1920 production of Le Sacre du Printemps, from the Ballets Russes program

The great genius of last night’s concert, however, was Diaghilev’s decision for Léonide Massine to re-choreograph Le Sacre du Printemps. Where Nijinsky’s choreography was rigidly beholden to Stravinsky’s score,[7] Massine’s was free and worked in counterpoint with the music. Massine did not hold fast to Nijinsky’s obsession with following the exact metric implications of the musical score, instead working with an aural sensibility that allowed the movement of the dancers[8]- who certainly seemed pleased to be working with this new choreographic idiom[9]- to flow organically, at times in opposion and at times completely in synch with the score. All of the bent-wrist-and-ankle awkwardness of Nijinksy’s choreography has been replaced in Massine’s glorious[10] scheme with movements reminiscent of Russian peasant dance.[11] The choreography thus perfectly reflects the Ballets Russes’s program note, which stated that Le Sacre is “a spectacle of Pagan Russia. The work is in two parts and involves no subject. It is choreography freely constructed on the music.”[12]

The Ballets Russes will perform this program on several more occasions in the following weeks,[13] and while audience members will likely have to choose between other exciting performance offerings at other venues, – just as I passed up the opportunity to hear Mozart’s Les Noces de Figaro at the Opéra-Comique![14] – they will surely not be disappointed in choosing the Champs-Elysées. The programmatic content of the evening perfectly highlighted Massine’s controlled, disciplined re-choreography of Le Sacre du Printemps, and the concert atmosphere was appropriately one of positivity and appreciation for great music.

Above is a Joffrey Ballet reproduction of the original choreography for the 1913 production of Le Sacre.

[1] “Courrier des Théatres,” Le Figaro, December 15, 1920, accessed November 18, 2015, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k292697q/f5.item.zoom, 5.

[2] Hermann Danuser and Heidy Zimmermann, etd., Avatar of Modernity: The Rite of Spring Reconsidered (London: Boosey & Hawkes, 2013), 468.

[3] Peter Hill, Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 30.

[4] Avatar of Modernity, 461. The 1913 premier included Chopin’s Les Sylphides, Carl Maria von Weber’s Le Spectre de la Rose, and the Polovtsian Dances from Borodin’s Prince Igor.

[5] “Le Tricorne,” Ballets Russes: The Art of Costume, accessed November 18, 2015, http://nga.gov.au/exhibition/balletsrusses/Default.cfm?MnuID=3&GalID=18.

[6] Shelley Berg, “Le Sacre du Printemps: A Comparative Study of Seven Versions of the Ballet” (PhD diss., New York University, 1985), 131.

[7] Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft, “Le Sacre de Diaghilev,” Vogue, April 15, 1965, 154. In this interview with Vogue from 1965, Stravinsky discusses what he perceived as the flaws in Nijinsky’s choreography, which were a result of the choreographer’s lack of knowledge of music and the concept of meter.

[8] Avatar of Modernity, 166. The author quotes Stravinsky in giving an example of this choreographic difference: in a place where the score included a bar of four beats followed by one of five, Massine had the dancers working in three groups of three, rather than in Nijinsky’s literal interpretation of four and then five.

[9] Clifford Bishop, “Spring is Busting Out All Over,” Sunday Times 20 (2003): 22, accessed November 18, 2015, http://search.proquest.com/docview/316748747?pq-origsite=summon&accountid=351.

[10] “Dancing By Massine Rich in Invention: He and Martha Graham’s Outstanding in Choreography at Stokowski’s Farewell,” The New York Times, April 24, 1930, 33. In the 1930 New York Times review of Massine’s first experience in the U.S., the author wrote that he “covered himself with glory.”

[11] Berg, 211.

[12] Ibid., 213. This is a quote from the program, found by the author in the Theatre Collection at the London Victoria and Albert Museum.

[13] Avatar of Modernity, 468.

[14] Le Figaro, 5.

You must be logged in to post a comment.