Dear Andre Levinson,

I have also heard of this Josephine Baker character that has arrived in Paris. As you have previously stated, the lady has caused quite a stir. It is clear that Paris is growing more and more fascinated in exotic dance and blackness, of which Miss Baker attributes to both. However, I shall make it clear to you that Miss Baker has made little, no, a nonexistent impact on concert music.

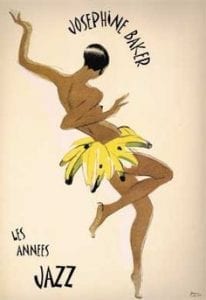

I have taken the liberty of attending a performance of Miss Baker’s at the Folies-Bergere.[1] To say that her performance was shocking wouldn’t have done the woman justice. Miss Baker performed her “banana number” and I immediately understood the disgusting obsession Parisian society has in relationship to the woman. The primitivistic nature of the dance mixed with the ideals of the “modern woman” is altogether mesmerizing.[2] I for one find Miss Baker revolting. I later witnessed the creature’s performance in La Revue Negre. Much like Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, the audience’s reaction was extreme to say the least. Accordingly, Miss Baker became a star overnight. Even more disheartening is the fact that this dancer’s provocative movements combined with jazz music has taken Paris by storm.[3]

Taking matters into my own hands, I decided to speak with Max Reinhardt and Harry Graf Kessler about this “rising dancer.” Despite my objections, the two are utterly fascinated with this woman. Reinhardt insists that her dance is nothing short of genius. Apparently, Miss Baker’s dance portrays emotion like no other dance is the definition of control.[4] I on the other hand see no trace of control. The way Miss Baker flails her arms shows no grace. Does Miss Baker express any skill at all? What of the hands? What of posture? The Charleston is not proper dance or ballet for that matter. For God’s sakes, at least point your feet! Miss Baker makes a grand jete look like a squawking bird. Furthermore, Kessler is convinced that the dancer’s performances is the perfect unification of ultraprimitivism and ultramodern.[5] Although, Kessler is also sure that Miss Baker’s dance holds no traces of seduction and exoticism.[6] After attending a performance, I admit that Kessler is wrong in that aspect.

Josephine Baker Singing 32:18 [7]

The extravagance of Miss Baker’s performances are out of hand. An American friend of mine introduced to me an article regarding the dancer and I couldn’t help but scoff. According to the San Antonio Sunday Light, Miss Baker included her own pet leopard in a performance. The beast proceeded to attack an audience member, who thankfully escaped without any serious damage.[8] Another credible newspaper by the name of the Kingston Gleaner points out the controversy of Miss Baker’s nudity and lack of costumes or fabric in general.[9] Obviously, I’m not alone in thinking Josephine Baker is unruly.

Inside the question of Miss Baker’s performance itself lies the issue of her popularity. I do not pretend to disregard the fact that Miss Baker is now une etoile dans la societe Francaise. As far as popular music in Parisian culture, I realize that this performer is the most talked about and reported upon artist in this Jazz Age. Miss Baker succeeds all other artists in that aspect and I suspect, sadly, that such will continue throughout history.[10] The woman’s dances showcase a part of culture that is rather new and intriguing; black culture. In many cases Miss Baker is innovative. On the other hand, I feel troubled when you say you have indulged in “pushing and following the fantastic monologue of ‘that crazed body.’”[11] Imagine my shock when you told me that Miss Baker isn’t simply “some funny dancing girl” but “the Venus Noire that haunted Baudelaire.”[12] I sincerely think you need to reflect on what you have told me. Miss Baker clearly not only caught your attention but the entirety of Parisian society. My point to you, dear friend, is that despite this fact, Josephine Baker hasn’t done anything to change the course for professional concert music.

Black culture and jazz bands have found its way into many composers and great works. Primitive rhythms and strong, bombastic percussion passages evident in the jazz genre can be spotted in concert music. La Creation du Monde by Milhaud is one such example. It’s arguable that Miss Baker has surely made a statement through dance and movement, but despite her association with jazz music, Baker doesn’t imprint herself in concert repertoire. There is nothing new about the music Miss Baker of which she dances along. The dissonances and percussive rhythms of Baker’s music isn’t what compels the audience. For instance, Milhaud refers to many artists and fellow composers in his writing but never mentions Josephine Baker.[13]

A good number of educated gentlemen denounce Miss Baker and the jazz style entirely. Bizet himself comments that “jungle-like moral world associated with (Baker and jazz) (is) wholly un-French and totally inappropriate for French culture.”[14] Albert Flament, in his column Revue de Paris, expresses concern over “the lasting marks that American jazz (has) left on French popular culture.”[15] Notice that Miss Baker is merely assumed as part of the jazz phenomenon. Jazz properties and characteristics were drawn upon before Baker become a star. Jazz’s characteristics have already tainted concert music. There is nothing new and, dare I say, appalling attributes that the lady could add to concert music other than dance.

I have spouted against Miss Baker quite a lot in my letter to you. I agree that Baker seems endearing and intelligent, but I’m afraid her impact on elitist music is limited. One does not listen to a song sung by Josephine Baker and contemplate the work’s counterpoint and various techniques.

Josephine Baker’s Banana Dance 16:42 [16]

Pardon for being blunt, but I know how passionate you are about this Josephine Baker. I would suggest not attending another performance until you can sort out your feelings. Despite Paris’s obsession over exotic dance and blackness, of which Miss Baker attributes to both, I urge you to reconsider this fascination. The woman is a pivotal performer, to be sure, but her mark won’t be seen on concert pieces. Instead of focusing on such characters, you should be revisiting the artistry of Palestrina and chant. The true French sound is in the classics and our roots. A pure and unified sound shall bring together our country’s national identity! Please consider attending a class of mine. Surely you will feel enlightened.

In any case, I wish you good health and that you go to one of my concerts instead of Miss Baker’s “tasteful” banana routine. Give my regards to your wife and children.

Be well.

Yours,

Vincent d’Indy

Colin, Paul. Josephine Baker in Revue Negre. 1929. “Le Tumulte Noir.” Editions d’art. Paris.

[1] Rose, Phyllis. “Top Banana.” In Jazz Cleopatra: Josephine Baker in Her Time, 81. New York, New York: Doubleday, 1989.

[2] Gumbrecht, Hans U.. In 1926: Living on the Edge of Time, 121. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 1997. Accessed October 5, 2015. Proquest ebrary.

[3] Josephine Baker: The First Black Superstar. Directed by Suzanne Phillips. Performed by Narrated by Josette Simon. BBC, 2006. Film.

[4] Gumbrecht, Hans U.. In 1926: Living on the Edge of Time, 66. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 1997. Accessed November 1, 2015. Proquest ebrary.

[5] Gumbrecht, Hans U.. In 1926: Living on the Edge of Time, 67. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 1997. Accessed November 1, 2015. ProQuest ebrary.

[6] Gumbrecht, Hans U.. In 1926: Living on the Edge of Time, 67. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 1997. Accessed November 1, 2015. ProQuest ebrary.

[7] Paris: The Crazy Years–Legendary Sin Cities. Films on Demand, 34:18 Canell, Marrin and Ted Remerowski. Films Media Group, 2005. Web. 6 Oct. 2015. <http://digital.films.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?aid+17396&xtid+48862>

[8] “Josephine Baker’s Latest Exploit.” San Antonio Sunday Light, 1930, Magazine sec.

[9] “Sharp Controversy.” Kingston Gleaner, March 14, 1928.

[10] Jordan, Matthew F. “La Revue Negre, Ethnography, and Cultural Hybridity.” In Le Jazz: Jazz and French Cultural Identity, 102. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010.

[11] Jordan, Matthew F. “La Revue Negre, Ethnography, and Cultural Hybridity.” In Le Jazz: Jazz and French Cultural Identity, 108. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010.

[12] “A Negro Explains Jazz,” The Literary Digest, 201. April, 26, 1919: 28.

[13] Darius Milhaud, “The Evolution of Modern Music in Paris and in Vienna,” The North American Review 217, no. 809 (April 1923), 544-554.

[14] Jordan, Matthew F. “La Revue Negre, Ethnography, and Cultural Hybridity.” In Le Jazz: Jazz and French Cultural Identity, 106. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010.

[15] Jordan, Matthew F. “La Revue Negre, Ethnography, and Cultural Hybridity.” In Le Jazz: Jazz and French Cultural Identity, 110. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010.

[16] Josephine Baker: The First Black Superstar. Directed by Suzanne Phillips. performed by Narrated by Josette Simon. BBC, 2006. Film. 21:12

[17] Colin, Paul. Josephine Baker in Revue Negre. 1929. “Le Tumulte Noir.” Editions d’art. Paris.

Other Sources

Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. “Josephine Baker” New York Public LIbrary Digital Collections. Accessed October 6, 2015. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/9c8ed400-ff54-012f-9a8e-58d385a7bc34

Garafola, Lynn. Legacies of Twentieth-century Dance. Middletown, Conn., Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2005.

Garafola, Lynn. Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

You must be logged in to post a comment.