June 24, 1923

El retablo de Maese Pedro

Exclusive Premiere

Princess de Polignac Home Theater

Last night there were a number of spectacular music concerts surrounding our lovely city of Paris. From Beethoven Sonatas at the Théâtre Edouard-VII to works by Brahms, Ravel, and Beethoven being performed at the Champs Elysées, there were various sights to be seen tonight under the Paris spotlights.[1]  I must say though that the greatest spectacle of them all was Manuel De Falla’s El retablo de Maese Pedro which I had the exclusive pleasure of attending by invitation.This production was held at the lovely Princess de Polignac’s home theater featuring various sized marionettes. The diverse as well as authentic elements of this work really made it stand beyond other French works deemed to present authentic “Spanish” exoticism.

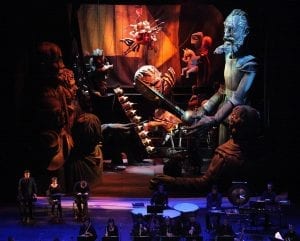

I must say though that the greatest spectacle of them all was Manuel De Falla’s El retablo de Maese Pedro which I had the exclusive pleasure of attending by invitation.This production was held at the lovely Princess de Polignac’s home theater featuring various sized marionettes. The diverse as well as authentic elements of this work really made it stand beyond other French works deemed to present authentic “Spanish” exoticism.

As some may know, Spanish exoticism has been thriving since its introduction by Debussy’s Lindaraja (1901) and Ravel’s L’Heure espagnole (1907-1909).[2]  Debussy and Ravel utilized what they perceived as Spanish music through their harmonic scheme and rhythmic expression; however, they only treated it at the most basic level.[3] Falla on the other hand, brings the true side of Spanish spice not only to his works but especially to this production. It really differs from the other French composers perspective of Spanish style. Ravel’s “Spanish” music is usually found to have advance motives of “fluidly with grandeur” while Falla’s revisits the same theme over and over, like a Spanish dance.[4] It is a dance that continues to radiate in the audience ears. Some may ask how this whirlwind of an opera came into existence? I am here to tell you there is an answer to this question.

Debussy and Ravel utilized what they perceived as Spanish music through their harmonic scheme and rhythmic expression; however, they only treated it at the most basic level.[3] Falla on the other hand, brings the true side of Spanish spice not only to his works but especially to this production. It really differs from the other French composers perspective of Spanish style. Ravel’s “Spanish” music is usually found to have advance motives of “fluidly with grandeur” while Falla’s revisits the same theme over and over, like a Spanish dance.[4] It is a dance that continues to radiate in the audience ears. Some may ask how this whirlwind of an opera came into existence? I am here to tell you there is an answer to this question.

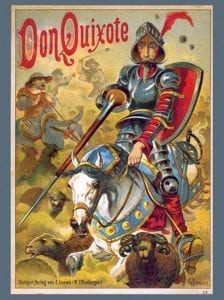

There was so much that was incorporated into what became El retablo de Maese Pedro. The piece was actually created from the immediate desire of the Princesse Ed. de Polignac.  She desired to have an opera performed for her private home puppet theater. De Falla held immediate interest into the project since it reminisced on his childhood when he used to play and invent puppet plays for enjoyment. This is what sparked his inspiration for the story. After searching a long time for the theme, he decided to set the subject on the titeres (marionettes) of Maese Pedro’s Puppet show displayed in chapters 25 and 36 of The Ingenious Knight Don Quixote de la Mancha, Part II by Miguel de Cervantes.[5]

She desired to have an opera performed for her private home puppet theater. De Falla held immediate interest into the project since it reminisced on his childhood when he used to play and invent puppet plays for enjoyment. This is what sparked his inspiration for the story. After searching a long time for the theme, he decided to set the subject on the titeres (marionettes) of Maese Pedro’s Puppet show displayed in chapters 25 and 36 of The Ingenious Knight Don Quixote de la Mancha, Part II by Miguel de Cervantes.[5]  He adds a very “unique adaptation and scenic presentation” to this specific episode of the story.[6] This added a new dynamic that the audience would not expect initially because they were used to what French composers had interpreted as Spanish exoticism.

He adds a very “unique adaptation and scenic presentation” to this specific episode of the story.[6] This added a new dynamic that the audience would not expect initially because they were used to what French composers had interpreted as Spanish exoticism.

In the show, Falla brings out a secret architecture to the work, a specialized form that cannot be characterized as an oratorio or opera but more so as a musical object. The story unfolds as a puppet show within a puppet show. The scene opens with the main singing characters Maese Pedro, his apprentice (the boy) and Don Quixote who are the larger puppets. They are accompanied by a larger audience that will watch Master Pedro’s puppet show. His puppet show tells the tale of how Melisendra, a Christian princess was saved from captivity of the Moors in Spain by Don Gaiferos, a Knight by way of the Court of Charlemagne. Within this production the boy narrates each scene of the story while Don Quixote and Master Peter watch from the sides while the audience puppets watch in awe and laughter. The opera reveals the turmoil that ensues within the drama of Master Peter’s Puppet show. This surprisingly brings out the deranged mindset of Don Quixote and his inability to identify fantasy versus reality.

Spanish music and the inclusion of various sized puppets created this genius of a show. Manuel de Falla exhibits an interesting flavor blend of Spanish tastes. I see the various flavors of his homeland of Spain in this colorful work of art he calls El Retablo de Maese Pedro, many that demonstrate the genuine side of Spanish music. But where exactly did he get these influences? And how exactly were they implemented? There are answers to to both of these questions, and I was able to solve the mystery by speaking to the man himself since he is a good friend from Granada.

At first, I found it highly unusual for a harpsichord to be brought to orchestra . Falla had the idea for using a harpsichord after his trip to Toledo during one Easter Weekend. It was while he was there that he visited the home of Don Ángel Vegué y Goldoni, a Fine Arts professor. At their home, Falla was amazed by all the antique keyboard instruments, including the various harpsichords and clavichords.[7]  As a friend I asked him more about his work. He told me that he decided to implement this “French” instrument into this work in order to appeal to the French public even though he was really trying to self exoticize his “Spanishness”. He also felt that the sound of the harpsichord brought a Spanish-like sound to the show. Falla was very much curious to how the French people would react to his production because being a Spanish composer in a French community was not easy to immerse himself in. But then again knowing him as a friend, Falla never bothered to succumb to the topicality of what was popular in French culture.[8]

As a friend I asked him more about his work. He told me that he decided to implement this “French” instrument into this work in order to appeal to the French public even though he was really trying to self exoticize his “Spanishness”. He also felt that the sound of the harpsichord brought a Spanish-like sound to the show. Falla was very much curious to how the French people would react to his production because being a Spanish composer in a French community was not easy to immerse himself in. But then again knowing him as a friend, Falla never bothered to succumb to the topicality of what was popular in French culture.[8]

I am simply amazed at the different aspects this opera brings through this puppet show. I must say the grave humour and beauty of language that De Falla utilizes in this opera make it the notable work it is. Being from Spain, Fall reveals a passionate seriousness but also humor within this story. Some say that he is distinguished from his fellow Spanish composers for his sense of “musical declamation”.[9] I can tell that Falla really implemented his Spanish roots into the piece in various places. For example, when Don Quixote is slashing the puppets to pieces, it’s theme suggests a Catalan dance heard in the hills near Barcelona.

Another moment of Spanish flare is the rhythm which is derived from the kind of tune sung by old Spanish ballad-singers of the era in which the story Don Quixote was written. Within this larger work, the Spanish language becomes the foundation for discovering and creating rhythms and cadences.[10] It creates this “poetic flow”[11] and “mysticism”[12] that makes his music so captivating to its listeners. In the words of Poulenc, it was like the work of “Renaissance goldsmiths, in which they connect, in an uneven and wonderful way, precious stones in a rich setting”.[13] It made me reflect on his discussion with me about his love of Spanish instrumentalists of the 16th century. He stated that they were among the first to play “an accompaniment of repeated chords to a vocal or instrumental melody” creating a combination of guitarra latina (playing chords) and guitarra morisca (playing melodies), popular characteristics of Spanish music.[14] As a whole, Falla brings a marvellous revelation of harmonic possibilities to the work far beyond what the normal listener expects.

De Falla utilizes a variety of opportunities to express his musicality in such a story. He seems to make sure that the piece maintains a Spanish quality even while still implementing classical elements. He forges the bridge between classical and Spanish folk music.[15] It is probably the reason for creating the setting for “only three singers and a band of twenty three performers” alongside harpsichord as an orchestral instrument.[16] He wanted to create the musical atmosphere of what Cervantes would have encountered. When chatting with him he discussed that the importance of the work was to express his nation and people of his homeland because they were his main sources of inspiration and the essential elements of his work.[17] Falla wanted to present the purest and most elevated model of Spanish art that has been created.[18] He emphasized that there is not just one style that represents Spain but there are actually different kinds of song and dance with their own different effects of rhythm and harmony that he wanted to express.[19]

Although some did not seem to enjoy the work’s structure, I believe it is a work of pure genius especially with the subtle elements he presents. What makes the piece unique is the miracle of how deeply felt the instrumentation is because it displays the underlying emotions of the characters.[20] I even bumped into my good friend Poulenc who also seemed to speak highly of not only the work but also of how admirable of a composer De Falla is.[21] He remarked that Retablo was one of his favorite Falla works and that it was “an incredible masterpiece”.[22]

He mentioned that this was the first time harpsichord was used as part of a modern orchestra and attending the final rehearsals of the work inspired him to incorporate it into a future concerto he is working on.[23] I feel Manuel de Falla is truer to any living composer demonstrating Spanish elements than any of his French colleagues. His music is profoundly Spanish and the success of his work is dedicated to endless possibilities of Spanish flares he displays.

[1] Le Figaro Newspaper, June 23, 1923. 2.

[2] Harper, Nancy Lee. Manuel de Falla: His Life and Music. (Scarecrow Press Inc 2005). 41.

[3] Trend, J.B.. Manuel de Falla and Spanish Music (Alblabook 1929). 40.

[4] Harper, Nancy Lee. Manuel de Falla: His Life and Music. (Scarecrow Press Inc 2005). 102.

[5] Demarquez, Suzanne. Manuel de Falla. (Chilton Book Company 1968). 119.

[6] Harper, Nancy Lee. Manuel de Falla: His Life and Music. (Scarecrow Press Inc 2005). 386.

[7] Harper, Nancy Lee. Manuel de Falla: His Life and Music. (Scarecrow Press Inc 2005). 101.

[8] ed. Nichols, Roger. Francis Poulenc: Articles and Interviews: Notes from the Heart. Interview 17: What Future for Music?(Ashgate Publishing Limited 1988). 281.

[9] Trend, J.B.. Manuel de Falla and Spanish Music (Alblabook 1929), 117.

[10] Trend, J.B.. Manuel de Falla and Spanish Music (Alblabook 1929), 118.

[11] ed. Nichols, Roger. Francis Poulenc: Articles and Interviews: Notes from the Heart. Interview with Nino Franck (Ashgate Publishing Limited 1988). 130.

[12] ed. Buckland, Sidney and Chimenes. Francis Poulenc: Music, Art and Literature. (Ashgate Publishing Limited 1999). 371.

[13] Harper, Nancy Lee. Manuel de Falla: His Life and Music. (Scarecrow Press Inc 2005). 103

[14] Trend, J.B.. Manuel de Falla and Spanish Music (Alblabook 1929), 41

[15] ed. Buckland, Sidney and Chimenes. Francis Poulenc: Music, Art and Literature. (Ashgate Publishing Limited 1999). 371.

[16] Trend, J.B.. Manuel de Falla and Spanish Music (Alblabook 1929). 122.

[17] Harper, Nancy Lee. Manuel de Falla: His Life and Music. (Scarecrow Press Inc 2005). 210

[18] ed. Buckland, Sidney and Chimenes. Francis Poulenc: Music, Art and Literature: Quoted from A bâton rompus, ‘Espagne’, autumn 1948.. (Ashgate Publishing Limited 1999). 371.

[19] Trend, J.B.. Manuel de Falla and Spanish Music (Alblabook 1929), 42

[20] ed. Buckland, Sidney and Chimenes. Francis Poulenc: Music, Art and Literature: Quoted from Poulenc in Moi et mes amis, ‘Manuel de Falla’, pp.122-123 (Ashgate Publishing Limited 1999). 372.

[21] ed. Nichols, Roger. Francis Poulenc: Articles and Interviews: Notes from the Heart. Interview 16: Musical Likes and Dislikes (Ashgate Publishing Limited 1988). 274.

[22] Harper, Nancy Lee. Manuel de Falla: His Life and Music. (Scarecrow Press Inc 2005). 102

[23] ed. Nichols, Roger. Francis Poulenc: Articles and Interviews: Notes from the Heart. Interview 7: Keyboard Concertos (Ashgate Publishing Limited 1988). 216.

You must be logged in to post a comment.