So, Why Do I Need An Ethics Lesson About Teaching Indigenous Musics?

Teaching Indigenous musics is a state requirement for music education in Minnesota (where this project is based). These musics are a critical component of this land’s history and present culture, worthy of respect and recognition. They’re also part of the home lives of many of Minnesota’s Indigenous students. But only 5.9% of educators in Minnesota are people of color,1 and only 0.5% nationwide are Indigenous, 2 indicating a serious lack of personal knowledge within the educational field pertaining to these traditions. Since the vast majority of Minnesota’s educators are not Native and therefore lack experiential knowledge of the knowledge systems, beliefs, and politics surrounding Native musics, many teachers are not well equipped to teach these musics in the ways they deserve and need to be taught.

It is all too easy to impose Western value systems and ways of understanding (such notation and harmonic analysis, which were created to understand and describe European music of a specific time period) upon Indigenous traditions, or to teach music without cultural context and thereby appropriate American Indian musics. In fact, even using the word “music” to describe all the sounds that might make their way into non-Native archives and music classrooms is an example of the problem: it is arguably an imposition of values to call these sounds “music” when not all of them are described or understood as such by the people who created them. I use the term music on this site for accessibility’s sake, but strictly speaking, the term that best describes Indigenous sonic landscapes without imposing a western label on them would be Traditional Cultural Expressions, or TCEs. As I said: avoiding such impositions of Western thought in the music classroom is extremely difficult when most teachers (including myself) lack personal knowledge of Indigenous identities.

Given the historical abuse of Indigenous knowledge by white settlers and the harm done to Indigenous peoples in schools, specifically, it would be fair to question why non-Native teachers have any right to teach Indigenous cultural expressions. We music educators bring folk musics from many cultures into our classrooms, but the aforementioned history of abuse of Native American culture by America, the country, means that extra care is needed when non-Native teachers work with Native musics. Put bluntly: to teach either historical or contemporary Native music indiscriminately would be appropriation.

However, that teaching of Indigenous musical materials is also a necessary act. Not least because Native and non-Native children alike need to understand the history of colonization, or the lessons of that history will be lost and past harms go unrepaired. Beyond that, we know in the education world that representation matters—Indigenous students in public schools deserve to see themselves represented by curricula, and thoughtfully including Native cultures shows our students that they are worthy of respect on both a personal and institutional level. We as educators have an obligation to teach the value and history of Indigenous musics, led in our methodology by Indigenous scholarship.

Since, as discussed, non-Native educators lack the personal knowledge to teach Indigenous musics ethically, we can reason that taking our lead from Indigenous scholarship marks the difference between teaching theft and teaching decolonization. The solution to that knowledge gap lies not in our non-Native educational institutions, but rather in the Indigenous scholarship and community-based knowledge published on the subject of Indigenous cultural expressions: only by following the lead of this scholarship can non-Native music teachers work ethically.

What Do American-Indian Scholars Say About This?

Great question. It’s complicated (of course) and this site’s full bibliography will give you an idea of what I’ve read on this matter. Essentially, discussion of teaching and hearing Indigenous cultural expressions breaks down into three main parts: sound theory, property rights, and cultural sovereignty.

Sound theory has to do with how Indigenous cultural expressions are heard by Indigenous and by non-Native people. The most critical component of this, for teachers, is critical listening theory, which Dylan Robinson wrote extensively about in his 2020 book “Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies.” Robinson writes that listening “is guided by positionality as an intersection of perceptual habit, ability, and bias,”3 meaning, people construct knowledge, including aural knowledge, based upon their own lived experience and how they were taught to relate to the world. Because Native and non-Native people have different positionality, non-Native listeners to an Indigenous sound would be quite literally incapable of hearing it and knowing it the way an Indigenous person would. This difference “is not to be understood as lack that needs to be remedied but merely an incommensurability that needs to be recognized.”4

Robinson also goes on to argue that the assimilation of Indigenous sound territories (cultural expressions) into classical spaces is actually an appropriative act that reifies the power of the state. However, if we non-Native teachers and students hear and explore Indigenous sound territories as guests, guided by the authority of Indigenous people who know these soundscapes better than we do, then we can try to understand these sounds in a less problematic way. This only happens if we let go of Western musical analysis and embrace new modes of listening.

Property rights are often thought of as a librarian’s or archivist’s issue—which is fair, and the legal conflict over ownership of historical materials is probably the least likely aspect of this discussion to actually enter a music classroom. However, it’s worth knowing that this conflict exists, so that we educators can conscionably use archives. The most important thing to understand is that the keeping of cultural expressions in settler-colonial institutions often entails their separation from their originating cultures, whose members may or may not have access to said institutions. Beyond that, laws governing copyright may actually make certain cultural expressions the “property” of the white people who recorded them, removing any right of governance from the Indigenous people who actually created these materials.5

While many efforts have been made to repatriate Indigenous cultural expressions from non-Native run archives, copies and originals still remain in the control of the US government, and archivists are making complex decisions—often on a case-by-case basis—to balance the mission of public access to history with the right of Indigenous communities to have control over their cultures.

The last issue in question is sovereignty, or who has the right to hear a recording of any particular cultural expression. Cultural expressions which westerners might hear as music can serve many purposes in their originating communities. For example, several American-Indian cultures have oral legal traditions which to Western ears are musical but to Indigenous ears constitute legal documents, as legitimate to them as a written contract is to an American court.6 Some cultural expressions are also regarded as sacred and are not meant to be heard by even uninitiated members of their originating tribe, much less by cultural outsiders.7

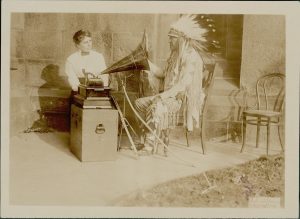

Mountain Chief (Blackfeet) listening to a song and interpreting it in sign language for ethnomusicologist Frances Densmore. Photo lot 24, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Historians acknowledge today that many of the TCE (traditional cultural expression) recordings taken by musicologists in the 19th and 20th centuries—including many of those recorded by Frances Densmore, whose legacy looms large in this field—should probably never have been made.8 It is difficult, if not impossible, for a non-Native educator to determine what historical recordings would be appropriate for a cultural outsider to learn or teach.

All three facets of this discussion lead to one essential conclusion: the most ethical action for any non-Native scholar or teacher to take in regard to recordings of Indigenous cultural expressions is to follow the guidance of Indigenous scholars and community members on how to use these materials. There are a wealth of recordings, songs, lesson plans, and other educational materials autonomously published and shared by their originating communities. The best materials to teach with are those which have been repatriated, contextualized into their history and their livings cultures, and freely shared again.

Rather than using western analysis, explore Indigenous people’s discussion of their own cultural artifacts. Reach out to contemporary American-Indian scholars and artists in your area, and invite them to share both present-day and historical musics, depending on their area of expertise. Rather than depending exclusively on archival materials to teach, find repatriated or non-archival cultural expressions to share with students. Teach and explore music as part of a living tradition, not just something that was archived and trapped at one point in time, a hundred years ago. Rather than teaching cultural expressions as “musics” and assuming all people have the right to hear them, teach with cultural expressions that have been freely shared by their originating communities, with permission for outsiders to learn from them. The “Educator Resources” page on this site contains Indigenous-created educational resources which, hopefully, will help empower non-Native educators to teach decolonization rather than appropriation.

1 “Arts,” accessed January 18, 2024, https://education.mn.gov/MDE/dse/stds/Arts/.

2 “Educator Workforce and Development Center,” accessed January 18, 2024, https://education.mn.gov/MDE/dse/equitdiv/. I couldn’t even find a statistic for how many Minnesotan teachers were Native American.

3 Dylan Robinson, Hungry Listening, Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies (University of Minnesota Press, 2020), 37–76, https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctvzpv6bb.4. 37.

4 Robinson, Hungry Listening. 53.

5 Torsen, Molly, and Jane Anderson. Intellectual Property and the Safeguarding of Traditional Cultures : Legal Issues and Practical Options for Museums, Libraries and Archives. WIPO, 2010.

6 Reed, Trevor G. 2019. “Sonic Sovereignty: Performing Hopi Authority in Öngtupqa.” Journal of the Society for American Music 13 (4): 508–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752196319000397.

7 Lyz Jaakola and Timothy B. Powell, “‘The Songs Are Alive’: Bringing Frances Densmore’s Recordings Back Home to Ojibwe Country,” in The Oxford Handbook of Musical Repatriation, ed. Frank Gunderson, Robert C. Lancefield, and Bret Woods (Oxford University Press, 2019), 0, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190659806.013.32.

8 “Returning Music to the Makers: The Library of Congress, American Indians, and the Federal Cylinder Project | Cultural Survival,” accessed January 26, 2024, https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/returning-music-makers-library-congress-american-indians.

You must be logged in to post a comment.