Greetings from the same laptop, new location! This weekend we are in Washington D.C. at the Library of Congress! Yes you read that correctly! I have been looking forward to this trip for a long time so to finally be here is a somewhat surreal feeling. There are a few Library of Congress buildings, and we are working in the Madison Building which houses Manuscripts and the Music Division to name a few collections. This is not the Jefferson Building which had a brief but important cameo in National Treasure Two: Book of Secrets (the famous scene where Nicolas Cage’s character discovers the Book of Secrets) but it is right next door. After checking in and receiving our library cards we started combing through the records of The Crisis, the journal of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, known as the NAACP.

Initially, our question was how to map the subscriber lists of The Crisis, which is still an option but would require resources of time and energy that are beyond the scope of the remainder of our CURI time. However, by looking through these records we learned so much more about the context of The Crisis within the NAACP. For example, one of my questions has been about segregated theaters in the North and how they functioned. While I don’t have any complete list of theaters that practiced racial discrimination, I did read through several cases of discriminatory practices at theaters in New York, New Jersey, and Kansas. In 1918, the New York State Legislature passed a bill specifically banning racial discrimination in theaters while in 1921 the Loews Theater in Harlem was guilty of refusing to provide seats to black patrons, even as there were black performers on stage. Patrons who had been turned away wrote to the NAACP. for assistance and legal advice on the matter.

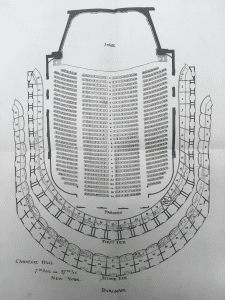

The NAACP also hosted a fair number of benefit concerts that could tell us more about the power in performance of the era. One performance I read about was Roland Hayes’ Carnegie Hall Benefit Concert in 1935. While I couldn’t find anything about Hayes performing Burleigh at this concert, there was a Carnegie Hall floor plan including the donors in each reserved box! Notice Gershwin in near the middle on the right side. The NAACP would reach out to individual donors and invite them to pay for a box. These were big opportunities to showcase the work of the NAACP during the year and to recruit new sources of money.

The more time I spend with these collections the more I am reminded that these were real people, with office conflicts and endless back-and-forths via the post, and frustrations, and real aspirations for progress. It is one thing to endlessly scroll through online newspaper archives and its another to hold a piece of paper in your hand with W.E.B. Du Bois’ signature on it. As we look ahead to the archives at Howard University and spending some time in other locations it is very likely that this mapping project will start to look different – potentially more of a mix of visual media and less about accumulating data points. How do we best contextualize Burleigh? How do we understand the constant naming of Burleigh as the finest and most well-known composer of spirituals when he is so often missing from relevant concert programs? What can we learn from his contemporaries like Nathaniel Dett and Maurice Arnold Stothotte, the latter who attended the National Conservatory at the same time as Burleigh, studied under Dvorak, went on to be a composer of concert band music, yet this was the first I have ever heard mention of him? What stories are we missing?

In the meantime, I’m just trying to soak it all in.

You must be logged in to post a comment.