Its been a week now since we first started on this mapping endeavor, which also means that I’ve spent the last week researching ancient organs in France. For our first assignment, I selected a map on the “La Diffusion de l’Orgue dans le Chrétienté Occidentale” or the Spread of the Organ in Western Christendom from the Altas Historique.1 This map placed dots at every location of an organ from the 1st to 15th Century. The dots were color-coded depending on eras from the 1st-9th Century, the 9th-11th, and each further century received its own symbol. There was no explanation about what kind of organs were on the map, despite the likelihood that viewers of the map would guess that an organ from the 2nd century could in no way be the same thing as an organ in the 15th century. Another issue with the map was that the remarkably large geographic reach, from Spain to Sweden, to Turkey which meant that the information was overwhelming and hard to make sense of.

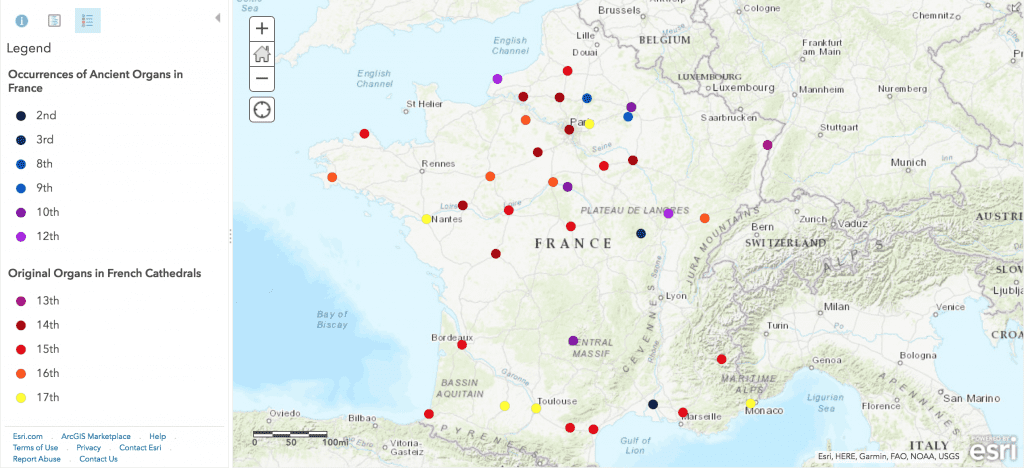

Together with my map partner, we decided to immediately narrow the scope of our project. We chose to look exclusively at France, partially because it showed a huge range of time, provided many data points, and we both studied French in the past which we thought would make it easier to comb through information. This was a choice that I don’t regret making, but I’ve started to understand how it puts some bias into what we are privileging in our new map, perhaps even implying that the French should be credited with the invention of the organ despite the fact that scholars are fairly certain it originated in the Byzantine empire. I researched primarily French organs between the 2nd and 12th centuries and Eric, my map partner looked at the 13th to 17th centuries. Our final map provides the option for pop-ups on each dot, which tells the viewer some information about where the organ is, how old it is, and what kind it is.

Parts of this project were undeniably interesting, to read about my struggles with Georgius click here, but in the end, our map doesn’t add all that much to the area of organ study. Our list is in no way exhaustive, and despite my many hours pouring through books about ancient organs, I’m certain there are so many more out there that could be found with the right tools. Something that I would like to think is an improvement upon the first map is that we tried to provide information about what type of organ each one was, or instead of putting a dot on a certain place that would indicate to the viewer that there was an organ there, the pop-up shows that a letter or piece of art mentions an organ, but that we have no evidence of that physical organ. This was something that couldn’t be discerned in the first map.

We tried our best – there is clearly a pattern on the map which suggests a consistently high volume of organs and mentions of the organ in the north of France, why is that? Why is there such a big gap in the lower middle third of the country? The far southern organs could be understood as part of the Roman Empire but is there more to that story? Almost certainly! However, ultimately I think this project can end where it is. Very early organ history is very difficult to pin down spatially, and therefore not really suitable for a mapping project. Newer organs are extremely well documented, and we wouldn’t really be adding anything new. This being said, I don’t regret working on this project, I’ve already learned so much about how important it is to do careful data collection and map making and I’m excited to apply these skills to our next project!

You must be logged in to post a comment.