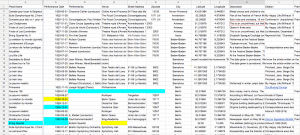

We are now up to 321 entries in our Milhaud performances spreadsheet. (Take a look here: <https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1-mSTi7F4Cw8WLE2q_qfRpJaAy-YzghOioJlrI2aPmbk/edit#gid=0>) But how did we get all this information?

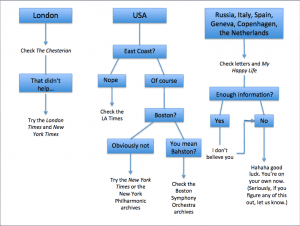

We’ve used a variety of primary, secondary, and tertiary sources to find information and fill in the gaps. Tertiary sources include Duchesneau’s catalogue Les Societes d’avant-garde musicale a Paris 1871-1939 and Annals of Opera. Secondary sources include Rittner’s “At the Time of Le Boeuf sur let Toit (The Ox on the Roof) Caberet” in The Thinking Space: The Café as a Cultural Institution in Paris, Italy and Vienna, Jane Pritchard’s Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe, and Catherine Hughes’ dissertation “Branding Brussels Musically: Nationalism and Cosmopolitanism in the Interwar Years.” The majority of our sources are primary sources, including newspapers (The New York Times, London Times, Los Angeles Times, Tagesbote, La Presse, Paris-Soir, Le Petit Parisien, Comoedia), periodicals (Melos, Anbruch, Le Ménéstrel, Musical Courier, The Chestarian, Le Guide du Concert), online archives/databases (Boston Symphony Orchestra archive, New York Philharmonic archive, Roger Désormiére website/archive, Vladimir Golschmann website/archive), letters (unpublished Milhaud letters, Hoppenot correspondence, Poulenc correspondence, and Correspondences avec des amis), and autobiography (Milhaud’s My Happy Life).

Ok, so we found a lot of sources, but how credible are they? Well, generally speaking, we can trust that a performance actually happened if a primary source mentions the performance after it took place (i.e. not advertisements/announcements for future performances). Here’s a list of kinds of primary sources from most to least credible:

- Newspapers, periodicals, and other archival materials that report on performances that have already happened. Newspapers and periodicals tend to be the most credible because they usually report on events that have already happened, and are written close to the date of its occurrence. The Boston Symphony Orchestra archives, New York Philharmonic archives, Melos, Anbruch, and Le Ménéstrel all fall under this category. Newspapers such as Comoedia, Tagesbote, Le Petit Parisien, and Los Angeles Times could also fall under this category, as long as they talk about performances that have already happened. But remember: newspapers and periodicals could also include mention of performances that have yet to happen, which brings us to our next level of credibility:

- Newspapers and periodicals that announce performances that will take place in the future. All the newspapers listed above could also fall under this category if they include announcements/advertisements for future performances, rather than reviews or summaries of recent past performances. Le Guide du Concert (a weekly guide to upcoming performances in Paris) also falls under this category. Although the performances listed in Le Guide usually take place, it doesn’t hurt to double check the existence of the performance in a newspaper or periodical that reports it after the fact.

- Letters and correspondence. Often, letters include mention of performances that will happen (but haven’t happened yet). These definitely need to be cross-referenced with a newspaper or periodical to confirm that the performance actually took place. Often, letters will include vague references to performances (e.g. “20 performances of my ballet will take place in Berlin in the next year”). While this information is certainly useful (we may not have known that there were any performances of this ballet in Berlin in that year), further digging is required (such as in the periodicals Melos and Anbruch) to determine exactly when and at what venue these performances took place (if all of them were actually performed).

- Autobiography (i.e. My Happy Life). Autobiography is the least reliable of all the primary sources. Often written years after the fact, the author may not remember everything completely accurately, or just leave out things. However, when the information is cross-referenced, the information found in autobiographies can be useful for discovering new research leads.

Secondary and tertiary sources are as reliable as their scholarship. Generally, the newer the secondary or tertiary source, the better, as new archives and sources are being discovered and utilized all the time. Knowledge is constantly revised, and catalogues expanded.

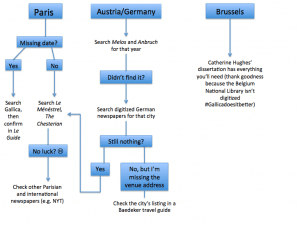

To start making our spreadsheet, each of us went through primary and secondary sources one-by-one, generating a preliminary, highly incomplete list of performances. Sadly, a single source rarely contains all the information about a performance that we want (date, venue, venue address, performers). Filling in missing information involves knowing where to look, and a little luck. Often, when we were looking for missing information, we found mentions of performances we didn’t have in the spreadsheet yet. It becomes a little bit of a never-ending cycle. For example, just going through an issue of Melos or Anbruch generates lots of new information on performances in Germany. Finding new performances and filling in missing information is often country- or region-specific. Here’s a handy flowchart (adapted and expanded from one Professor Epstein drew last week) for finding missing information:

Research Links:

Gallica: http://gallica.bnf.fr/accueil/?mode=desktop

German historical newspapers: https://eudocs.lib.byu.edu/index.php/Historic_German_Newspapers_and_Journals_Online

Austrian historical newspapers: http://anno.onb.ac.at/anno-suche#searchMode=complex&text=Milhaud&dateFrom=01.01.1921&dateTo=31.12.1939&from=1&selectedFilters=type%3Ajournal

You must be logged in to post a comment.