From the beginning, Ida Rubinstein’s life was anything but average. Born in 1885 to wealthy Jewish parents and orphaned nine years later, she was brought up by a wealthy aunt in St. Petersburg, where she received a top-of-the-line European education (multiple languages, philosophy, the fine arts, etc.), and benefitted from a constant exposure to high culture. This exposure gave her an appreciation for the arts that persisted throughout her life. As a young woman, she became enamored with her body, and adopted an enigmatic, artistic persona that drew the attention of everyone who saw her. She was not satisfied with simply observing art, dance, and music; she wanted to participate in the buzzing European art scene. Unlike most artists with this ambition, however, Rubinstein’s parents had left her a massive fortune when they passed away, which she decided to use to finance her career as a performer.

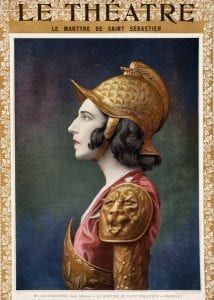

Russian dancer Ida Rubinstein (1885-1960) in role of San Sebastian, in Le Martyre de Saint Sebastien by Claude-Achille Debussy (1862-1918) From Le Theatre in June 1911

Rubinstein (pictured at left) was quite beautiful, but had no classical dancing skill. Nonetheless, she was determined to perform the lead role of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé. Because the Russian Orthodox Church forbade theaters to depict sacred characters on stage, Salomé could not be performed as written; upon discovering that Vera Komissarzhevskaya was to direct a non-religious adaptation of the work (renamed The King’s Daughter), Rubinstein wrote to him and requested to perform the lead role. When he refused her, she commissioned composer Alexander Glazunov and set/costume designer Léon Bakst to help her produce the play herself. She also enlisted the help of the dancer Michel Fokine to give her private lessons so she could prepare for the role. To circumvent the Church’s ban on theatrical interpretations of sacred characters, she distributed the play’s text to audience members weeks in advance, intending to perform the work silently; but even with the text removed, the police appeared on opening night to confiscate the head of John the Baptist, which they would not permitted on stage. Although the loss of John the Baptist’s head meant that Rubinstein had to mime to an empty platter, the production was highly successful. Her Dance of the Seven Veils, in which she removed almost all of her clothes, was particularly well received.

Rubinstein was not a particularly good dancer, but her peers admitted that she had a uniquely captivating and alluring way of moving on the stage. Serge Diaghilev, impresario of the famous Ballets Russes, agreed, and cast her as the title character in Fokine’s newly reworked ballet Cléopâtre. Rubinstein’s performance in this ballet was a great success, but she did not feel obligated to remain with Diaghilev. With her vast financial resources, she had no need for him, and in 1928, she founded her own ballet company. Diaghilev disliked having to compete against another Russian ballet company, and when Rubinstein hired several composers, set designers, choreographers, and dancers that had previously worked for him, he became angry. In a series of letters, he vehemently criticized several of the works that Rubinstein premiered, including Stravinsky’s Le Baiser de la fée and Ravel’s Boléro. In one letter, Diaghilev wrote:

Paris is a terrible city. One hasn’t five minutes to write a couple of words. Everyone has come and there’s terrible confusion. I’ll start with Ida – the house was packed, but the corwds had been planted by her. However she didn’t send any of us a ticket … The performance was nothing but provincial boredom. Everything was interminably long, even the Ravel which went on for a whole fourteen minutes. The worst of all was Ida herself … She was a total failure. She can’t dance at all … (Cited in Scheijen 427)

Diaghilev’s bitterness towards Rubinstein is evident in his assessment of her work, but there is some truth to his criticism. What made Ida Rubinstein famous was not her talent as a dancer — she did not start ballet young enough to develop any remarkable skill — but her complete disregard for the rules. When she was not given the lead role in Salomé, she produced her own version of the play. When her disapproving family diagnosed her with a mental condition, she married her cousin Vladimir to avoid being locked up. (She maintained a strict “no sex” rule with Vladimir, and left him at home while she went off to build her career. When he approached her to demand a divorce in 1918, she refused to grant it, and he disappeared a few years later.) She had affairs with both men and women, including American painter Romaine Brooks, with whom she fell madly in love. In a word, she did what she wanted to do.

Rubinstein was a quirky woman. As Gabriele D’Annunzio, another of Rubinstein’s lovers, said, “She has only two idols, her art and her body.” Indeed, Ida’s body seemed to be the focus of her art. She never lost an opportunity to take off her clothes, in public or in private; with her erotic dancing, she took the portrayal of the female body into her own hands, wresting control from the men who dominated the European art scene. Rubinstein was a symbol of unrestrained sexuality. As Toni Bentley writes of her 1908 premiere of Salomé, “Never before had a young society woman of such impeccable upbringing been seen dancing so voluptuously to oriental music” (139). Her dancing was not the only thing that defied gender norms; she was an avid fan of big game hunting, and kept a live panther and tiger in her Paris apartment. When Diaghilev visited her apartment with a new contract, the panther decided it did not much like his coat, and leapt across the room at him. A very surprised Diaghilev jumped onto the table, screaming in terror and frightening the panther, which was moved to the next room. Naturally, Rubinstein found the incident hysterical, but Diaghilev was supremely offended, and lost all interest in working with her after that visit.

Ida Rubinstein was a rich, attractive, popular, influential, and fearless enigma. Her impact as a promoter of eroticism and freedom of sexuality was significant, and she commissioned several important works, including Stravinsky’s Le Baiser de la fée, Debussy’s Le Martyre de Saint Sebastien, and Ravel’s Boléro, one of the most popular orchestral works of the late 1920s. Her uniqueness and vivacity made her an important and highly influential character during her lifetime. She did not impact musical styles as much as she shaped the general character of the musical and artistic scene of the early twentieth century.

Works Cited

Bentley, Toni. Sisters of Salome. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

“Russian Dancer Ida Rubinstein (1885-1960) in Role of San Sebastian, in Le Martyre de Saint Sebastien by Claude-achille Debussy (1862-1918) from Le Theatre in June 1911”. 2014. In Bridgeman Images, BridgemanImages. London: Bridgeman.

Scheijen, Sjeng. Diaghilev: A Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

You must be logged in to post a comment.