“It would even be dangerous for composers systematically to ignore the productions of their foreign colleagues and thus to form a sort of national coterie: our musical art, so rich in the present epoch, would quickly degrade and enclose itself in clichés…”1

I wouldn’t have thought this quote came from Ravel in the teens, considering France and Europe in general were in its heyday of chauvinism during this time period. However, although many French and Austro-German artists brandished nationalism in their works and statements, a significant amount of attempts to cultural openness and degree of mutual acknowledgement existed between some music elites of France and Germany. In 1920, sponsored by the French embassy for the purpose of “rapprochement,” Ravel and Casella visited Vienna for a series of concerts introducing French music. One year later, Milhaud and Poulenc gave several concerts in Vienna, where they met Schoenberg and his two students, Alban Berg and Anton Webern. In December of the same year, Milhaud conducted the French premiere of Pierrot Lunaire in Paris. The next year Milhaud returned to Vienna conducting the same piece together with Schoenberg himself. On the other side, Schoenberg also made efforts for cultural communications by actively organizing performances of music by French modern composers in his Society for Private Musical Performance in Vienna.2 In a letter he wrote to Zemlinsky discussing the concert program of the “Society,” he argued,

“Now as to the ‘insignificant’ Milhaud. I don’t agree. Milhaud strikes me as the most important representative of the contemporary movement in all Latin countries: polytonality. Whether I like him is not to the point. But I consider him very talented. But that is not a question for the Society, which sets out only to inform. It was actually primarily on your account that I did Milhaud once again, hoping that he would interest you.”3

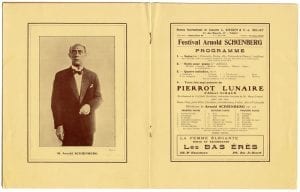

Finally in December 1927, facilitated by Ravel, Société Musicale Indépendante invited Schoenberg to Paris for two concerts titled “Schoenberg Festival.”

Concert Program Image Archive at Arnold Schoenberg Center

Full Concert Program

At the concert, Schoenberg not only conducted several representative works of him, such as the famous Pierrot Lunaire and Pellás and Mélisande, but also world premiered his new chamber work Suite Op.29.

A recording of the original performance is archived at the Schoenberg Center:

Historical Recordings – Arnold Schoenberg Center

In the interview after the concert, an editor from Comoedia asked Schoenberg about his opinion on the development and relationship between French and German music. It was a tricky question, and Schoenberg answered after a while of thinking:

“In my view the development of German and French music runs parallel. Both are against the ‘pathos’ that was in full bloom twenty years ago…Romanticism no longer exists… I want to emphasize ‘pathos’ once more – the grandiloquence of music of the past. It was music that didn’t operate through the ideas it contained, but only through the composer’s emotion, yes, sometimes only through his sentimentality. Today, be it France or Germany, we demand a music that lives through ideas and not through feeling.”4

From Schoenberg’s own words we know that he had a pretty good insight of French modern music, at least that represented by Les Six. Despite his cautious tone, Schoenberg probably pointed out the truth, that the motivation to create music that outshine the past was more similar than discrete between France and Germany.

Footnotes:

1 cited in Jane Fulcher, The Composer As Intellectual: Music and Ideology in France 1914-1940 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 67.

2 Ibid., 182, 362.

3 Arnold Schoenberg and Erwin Stein, Arnold Schoenberg Letters (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1965),79.

4 Walter Frisch, and Bard Music Festival, Schoenberg and His World (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1999), 271.

You must be logged in to post a comment.