Upon first reaction to reading both the Dorf and the Moore articles, I was completely of the mindset that there is no way to find something gay in music. Much like the discussion we had in class about Germaine Tellefairre’s music and how we could find nothing that struck us with: “This was written by a woman!”, I was of the mindset that there was nothing in either Poulenc’s music or the music of Satie’s commissioned by the Princesse de Polignac that was overtly gay. My mindset began to shift when both the articles discussed their music in the social, political, and sexual realms of outside life. There is no such thing as music that is not affected by some sort of social, political, or other outside force, so why can’t there be gay music? I’m not sure so much that the articles were convincing in their claims that the pieces were gay because of this or that explicitly in the music, but together they both changed my mindset with their assertion that at least something about the pieces were affected by the sexuality or wanted perception of the sexuality of the composers/commissioners.

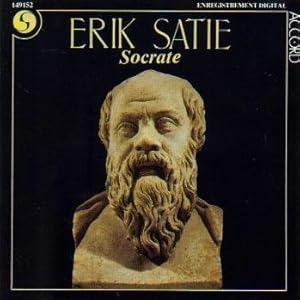

The most convincing piece of evidence I found in the Dorf was women reciting and performing anything in the Greek language was considered “Sapphonic”. The mutual understanding of both Polignac and Satie’s precarious sexual position in the public realm was very important for keeping the rest of the work’s sexuality or display of sexuality completely under wraps. It was a curious decision to use the text that they did from Symposium between Alcibiades and Socrates, which outlines a sexual relationship between the two, and then completely obliterating any allusion to sexuality or body form, etc.

Another form of hiding sexuality is in the music itself. This music is very simple, neotonal, and modernist. The purpose of the music was to harken back to ancient times, which masks even further any sexuality displayed in the piece. The restraint in the composition process mirrors directly Polignac’s restraint to public sexuality, the opposite of her acquaintance Natalie Barney.

The camp aesthetic articulated in Moore’s article is another strong case for finding homosexual allusions in everything surrounding Poulenc’s music. The decision to hide anything that anyone could consider homosexual in a show-y and theatrical manner is definitely a political as well as a musical move. The tonal “virgin” characters in Audube exemplify heterosexual purity, and Diane has sections of chromaticism that show her sexual or intimate nature. Interestingly enough, Poulenc also hides his sexuality in themes meant to evoke mythology. These two ideas were in dialogue and debate throughout the piece. This is another example of Poulenc’s sexuality in and around his music. I felt that this claim was fairly agreeable.