It’s interesting that two important people in the history of french music both identified as queer. The Princesse Edmond de Polignac, along with Francis Poulenc, were gay. The Princesse and her parlor concerts were known throughout France, and she commissioned many great pieces from up and coming composers. She even had a piece written by Poulenc himself. Poulenc’s sexuality was kept a secret, although he openly discussed it while he was alive. Now that said, I hadn’t thought that their sexuality could have pervaded the music they required and wrote, until I read these two articles by Samuel Dorf and Christopher Moore.

Dorf argues that the Princesse had a lesbian aesthetic for her parlor, and for the music she subjected her guests to. I found this somewhat convincing, but to me, I could have easily just stuck with the argument that she was simply looking for a certain neoclassicist style. Within Satie’s work, Socrate, that the Princesse commissioned, there are many notes of new, neoclassic harmonies and tonal structures. But it certainly was interesting to note that the text of Erik Satie’s Socrate was “sex-ed down.” It is clear that both parties went to great lengths to remove any reference to sex from Plato’s original work.1 The characters are painted as Asexual, which too is convincing that the Princesse meant it to be a queer work of art. However, the climate of her salon, and the relationship between her and her previous lovers, doesn’t seem to have an affect on the piece she commissioned. Sure, it has a great influence, especially since most of her audience was her close female friends, many of whom were aware of her sexuality. She went to great lengths to hide it, and it seems almost impossible that she would even let some if it escape into the music she assigned her name to. I think it has a great deal of influence, like the inclusion of four “sapphonic” sopranos that Dorf claims are voices lesbian musical possibility, or the scandalous characters of girls dressed as pageboys. I do not believe however that her lesbianism completely colors this piece, or any other that she had commissioned during her lifetime.

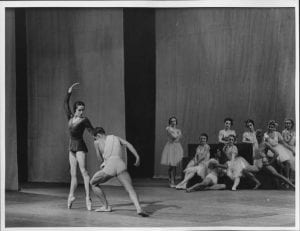

Poulenc, however, was very open with his sexuality. He often sent letters to his male friends with flirty, inappropriately homosexual banter. At the beginning of Moore’s article, he even states that the American Composer Ned Rorem was surprised and uncomfortable with Poulenc’s talk of his sexual exploits. It makes more sense to me that Poulenc would incorporate his homosexual readings of society into the works he created. It’s an important argument to acknowledge that this is prevalent specifically in his ballet Les Biches. Now, I just wrote an essay on the notions of sexuality in Les Biches, so I could go on for ages. Moore points out that there are specific scenes in which androgyny, cross-dressing and same-sex desire are present. Nijinska’s choreography often shows two same-sex characters feeling each other up during a dance, or in some other way fueling the notion of homosexual lust.2

Even more convincing too is the Woman in Blue’s Adagietto. During this scene, a love theme is presented that modulates extensively, and is passed through many of the instruments. This modulation seems to point towards a love that’s not quite what it seems. During this whole scene, The Woman in Blue herself is dressed in a blue suit; designed and worn by men at the time. It’s this notion of a woman in man’s clothing that Moore cites Lynn Garafola as believing to be “an old-style ballerina in ambisexual drag or a fabulous drag queen who happens to be female.”

It’s clear that there are homosexual notions in Poulenc’s Les Biches. There is discernable evidence pointing to this, whereas with The Princesse, it’s more of a speculation. Both people are important in Queer history, though Poulenc was more open with his sexuality.

1 Dorf, Samuel, “‘Étrange, n’est-ce pas?’ The Princesse Edmond de Polignac, Erik Satie’s Socrate, and a Lesbian Aesthetic of Music?” FLS: Queer Sexualities in French and Francophone Literature and Film 34 (2007), 87-99.

2 Moore, Christopher, “Camp in Francis Poulenc’s Early Ballets,” Musical Quarterly 95 (Summer-Fall 2012), 299-342.

You must be logged in to post a comment.