Throughout the 1920s, an exotic wave of culture swept through most of France. Jazz became a prevalent aspect of French life, and artists such as Josephine Baker become phenomena. Music Historians often refer to this so called obsession with African American culture “Negrophilia.” Parisians were entranced by this new style of movement and music, and they filled the seats at many performances of this type of music. But while I’m sure that people themselves felt a love for black artists, their racism and appropriation for the stereotypes of the culture pervaded that love, leaving only infatuation.

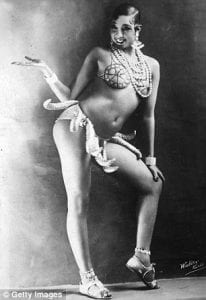

When the lovely Josephine Baker began dancing La Revue nègre, she captured the attention of the audience. Her dance was provocative, alluring and sensual. It was completely different from the classical, or even the more modern steps, that ballet-goers were used to. André Levinson, a journalist of French Dance in the 20s, believes that the most characteristic thing about the ‘Negro dance’ is that “the steps…are based on a direct and audible expression of rhythm.” 1 This is what entranced the audience so much. But as Levinson goes on to explain, “we should not, however, jump to the conclusion that because of this extraordinary rhythmic gift alone the negro artist or musician should be taken seriously.” He believes that dancing which is enslaved to rhythm is inferior, and is “no more than a decoration.” This, coming from a pretty influential and respected person in the art community of France is extremely troubling. The expression of anything, from anyone of any culture, is not inferior to another. Simply put, other cultures must be respected. France was infatuated with this new style of dance simply because it was different, and inferior to their type of classical ballet. They enjoyed going to see performances of the negro dance, but didn’t take the artists seriously at all. Again, it was the draw of the exotic that caused them to enjoy the spectacle of black artists on stage before them.

It too was this idea of primitivism that captivated audiences. The Negro Dancer was inferior, yes, but they were also seen as a primitive peoples. Rhythm was seen as something anyone could do, again just a decoration. Black music was below the extravagant music that the people of France were able to create.

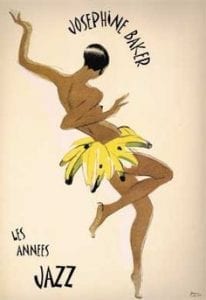

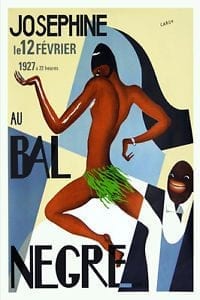

For Josephine Baker specifically, it was the exoticism of her rhythmic dancing, and, ultimately, the sex appeal of her darker skin, that entranced audiences. Eventually, she did become a respected artist, but it was her initial ‘different-ness’ that drew them to her. On posters that advertised her, she was almost always barely covered by a few jewels. Even in artistic drawings of her, for posters of performances, she was often bare-chested, again perpetuating the primitive-ness of her black skin. To get audiences, her sex appeal was exaggerated and her black skin was accented. This is not a love and respect for an artist, but an infatuation with the alien.

Poster for Josephine Baker’s performance of Les Annees

Not everyone in France was a huge fan of this exotic invasion. At first, critics of Jazz were, too, entranced by this new fad. But after a while, claiming that “jazz was a foreign influence wreaking havoc on French culture,” 2 they too turned away from most African American artists. The black artists in France, harshly critiqued, were only popular because of France’s fascination with the unfamiliar. They were not respected, at all. Josephine Baker was an objectified item of sex and primitive, ethnic dancing. Jazz itself was stolen, and used as decorative flairs in French composer’s pieces. It’s clear that the French people loved African American artists, and what they were doing, but did not respect nor honor them. It was not a pure love, but a lust and infatuation with “Les Nègres.”

1 Levinson, André, Joan Ross. Acocella, and Lynn Garafola. André Levinson on Dance: Writings from Paris in the Twenties. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan UP, 1991. Print.

2 Jordan, Matthew F. Le Jazz: Jazz and French Cultural Identity. Urbana: U of Illinois, 2010. Print.

You must be logged in to post a comment.