The great responsibility of a historian is to ask questions to which there are no correct answers.

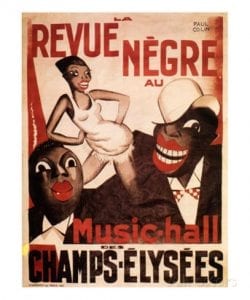

Did the 1920s Parisians love, respect and celebrate African Americans artists? Or did their racist view ultimately meant that what they experienced was something other than love?

Was their’s a fascination or a degradation of African and African American culture?

Although dates and facts are presented in an objective way, human experience and perception greatly influences the course and memory of history. Even within the limited sources we read, the varying responses to African American artists shows how many different perspectives existed simultaneously.

What is clear is that regardless of individual love, respect, fascination, distaste, disrespect, or degradation of African/African American culture and people each perspective we have encountered displays a two-dimensional view of said culture and people.

In Paris in the 1920s “the idea that authentic jazz was a direct offshoot of la musique negre had become a standard trop in French debates on music” (Jordan 103). Even this basic assumption is one that has plagued the musical community for decades. Both then and now stereotypes of cultures and music caused more music to be created, thus reinforcing the very stereotypes that had inspired the music. The combination of primitivist and nationalist culture was strong and in many ways defined the musical landscape of the time.

Paris-Midi critic Paul Archard displayed both the two-dimensional perspective and the infusion of primitivism and nationalism into music analysis. He focused on the “other,” associating the shows of Josephine Baker as something separate from Frenchness, even though it came about and became a spectacle as a response to the French people’s own fascination with the subject matter. The cyclical relationship between art and audience is conveniently left out (Jordan 104).

Conversely, critic Jacques Patin embraced the idea that the troupe was a “ultra-modern” group (Jordan 104). He took the same performances and interpreted them through a different two-dimensional filter… thus coming to a different, equally subjective conclusion.

Parisians in the 1920s and later had many varied ideas and perceptions of both African and African American cultures (Jackson 85). None of them could truly do justice to such a large group of diverse, unique peoples. Individual critics, composers and audiences chose to focus on certain aspects of culture(s) that they did not truly understand, creating inaccurate, two-dimensional versions of such rich artistic traditions.

So what do we do with this knowledge?

Knowing that it is human nature to assimilate difference and “otherness” into our own cultural understanding of the world, it is our job as historians, performers, and listeners to embrace the art of many different places and respect it, while also being aware of the various prejudices and inaccuracies woven into the fabric of history through art. We must be honest with ourselves about our own history and the appropriation of different cultures, and we must strive to represent every voice throughout history, not simply the dominant one.

You must be logged in to post a comment.