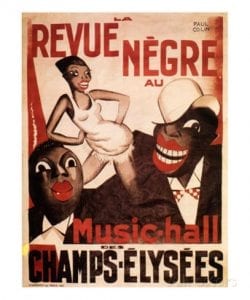

Crucial to any discussion of a historical cultural phenomenon is an acute awareness of the myriad factors at play within the context in which the phenomenon occurred. While we may be shocked into a moment of rage upon our first read of such accounts of La Revue Negre as that of French dance journalist André Levinson, it would be a mistake to let our analysis stop there, with the bitter taste of blatant racism lingering in our mouths. We must instead train ourselves to (at least temporarily) relocate the bitterness to the back of our mouths as we taste the rest of the meal, which includes the rich fare of the cultural, social, political, and economic goings-on of 1920s Paris. In light of the crisis of national identity at the forefront of the Parisian cultural mind and of the economic stability of postwar France, the attitudes of critics and of the public towards Josephine Baker and her cohorts lose some of their shock value: it is almost as if a phenomenon of this sort had been brewing long before it surfaced in the form of a fervent obsession with La Revue Negre.

Josephine Baker, lead dancer in La Revue Negre, was described by Levinson as “a sinuous idol that enslaves and incites mankind” (74).

Jordan’s explanation of French “cultural ambivalence” surrounding the reception of La Revue in our excerpt from his book on jazz and French cultural identity provides ample evidence for this argument. He demonstrates through illustrative quotations from French critics of the day that the attitude toward La Revue and its music and dance combined language dripping with the cultural fascination with all things negre (which carried with it tones of exoticism, primitivism, and “otherness”) and that of the avant-garde and “new.” Many critics either praised La Revue for its newness and thus for its subsequent ability to distract the French public from its pressing economic crises or criticized it for its startling and unexpected qualities. This ambivalence, while not in any way admirable (ideally the racialization of La Revue, with all its overtones of French cultural superiority) would not even exist, makes a certain amount of sense in light of the atmosphere of France during the 1920s.

My insistence upon the coherence of the cultural ambivalence surrounding Paris’s fascination with La Revue Negre is not intended to condone the idea of negrophilia; it is simply to argue that, while the inflammatory and shocking language used by critics to describe and respond to this new kind of music and dance was and is inherently offensive, it is not offensive in the same way that it would be in the United States in 2015. Multifaceted historical contexts are crucial to an understanding of a particular cultural attitude, and that of the negrophilia of 1920s Paris is no different.

You must be logged in to post a comment.