What exactly delineates Parisians from their immigrant counterparts?

Long ago, as I started looking into the spread of immigrant population within the city limits of Paris (say, two, maybe three weeks ago?), I knew that I would encounter certain difficulties. For one thing, France is in an entirely different Republic than it was in the twenties; while they may or may not maintain detailed records today, I couldn’t be sure how policy shifts and interim disasters (yes, I mean the second World War) had affected the records left from that period. For that matter, who could say whether records had ever been kept? Certainly nowadays many immigrant groups have a variety of motivations for mistrusting government interference and staying well under the radar – as in, completely off of it. And while the everyday Parisian likely noticed when their new neighbors spoke a variety of tongues not native to France in any of its departements, the natural tendency for human curiosity (also called, in some instances, incurable busybody-ness) is more often than not tempered with the equally natural tendency for human self-preservation, or not getting involved.

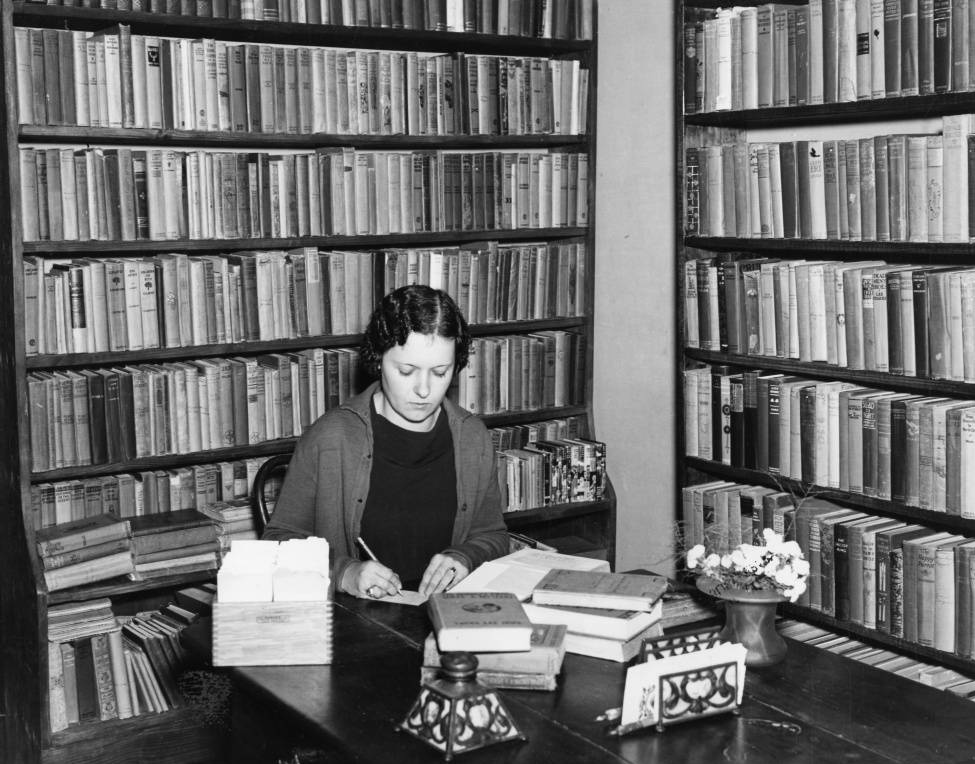

Consequently, I was prepared for the difficulties ahead. Little did I know of the awesome (correct use of the word) power of … research librarians.

*a brief and shameless plug; if you have not thanked your local research librarian of late, please take the time to do so. These ladies and gentlemen are absolutely marvelous*

Before I was truly aware of what was happening, I had an entire inbox full of sources and suggestions. Evidently, someone in 1920’s Paris was good at chronicling.

In fact, the only real difficulty to arise was this: that immigrant populations are nefariously difficult to pinpoint on a metropolitan plan. To put it bluntly, it will not be easy to map. However, there is a good deal of information on especially what groups were resident in or arriving to Paris during the period of interest. Already present from an earlier wave of immigration were Germans, Belgians, and intranational migrants from the other provinces, such as Provence or Normandy. Arriving (in some cases verily en masse) were Russians fleeing the Bolshevik Revolution and subsequent Civil War, Armenians fleeing genocide in the former Ottoman Empire (present day Turkey and surrounding areas), Italians fleeing Fascism, and other influxes from French colonial holdings. Russian and Polish Jews had arrived somewhere in between, fleeing the pogroms in Eastern Europe.

Now, much of that reflects American immigration trends of the same period, with some exceptions (the United States had quotas already in effect to control who could immigrate). However, therein ends most of the similarity. Coming from an American perspective, I assumed that most immigrants would stay in communities of shared cultural affiliation within specific blocks of the city, as many (though admittedly not all) had done in cities like New York or San Francisco. What I expected was to be able to pinpoint Chinatown’s, Little Italy’s, and Armenian neighborhoods and easily mark them on the map.

As it turns out, the matter is much more complicated.

Some did, some did not. There was considerably more assimilation, simply because Paris was more expensive than other cities with high immigrant populations at the time, like Berlin. Shopping for the best-priced neighborhood seems to have been more important than finding the right cultural community. At times, since immigrant masses often shared socio-economic status as unestablished new arrivals, this did concentrate different ethnic populations. On the whole, though, most cultural groups that we might identify as discrete were spread out. Some, such as the Jewish residents of Paris or the Italians, had different divisions within their “culture”. One might recall that not all Jews or Italians are the same, given the regional differences in customs, language or dialect, and beliefs. Working on this particular project made me recall how often we in the present day forget or ignore the fact that political categories as they exist today are relatively recent entities.

I have been able to narrow down some general quarters in which it would not be unusual to walk down the street and encounter a different, non-Parisian community within the larger city-scape, yet overall the immigrants to Paris tended to blend with their “native” Parisian neighbors as much as they could. Which is not to say that there were not cultural conflicts or race tensions within the city; it simply serves as a caution against assuming the “us” vs. “them” mentality.

You must be logged in to post a comment.