Erik Satie in 1909

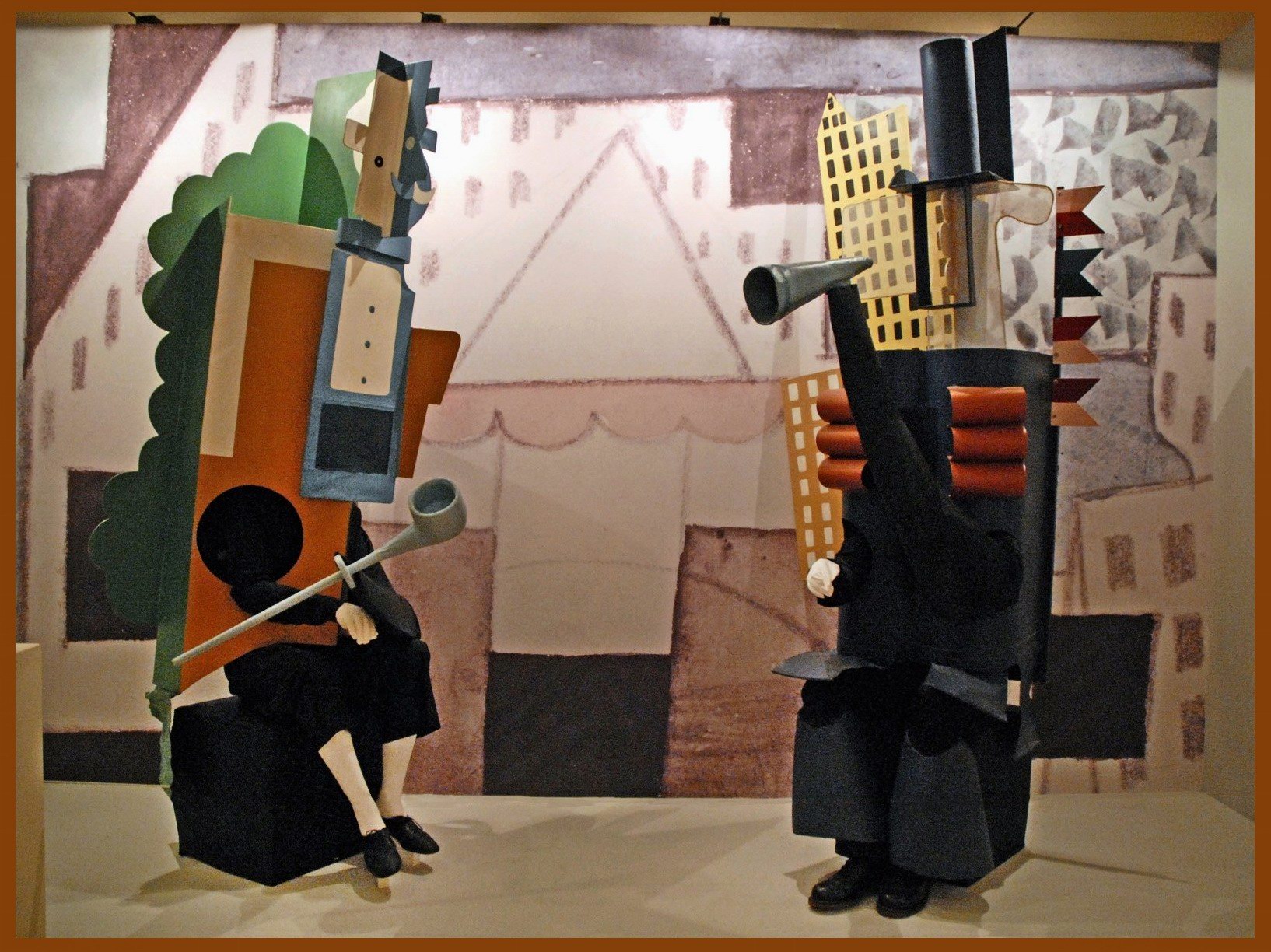

Erik Satie (1866-1925) was a French composer from Normandy; he studied at the Paris Conservatory (which he despised) and in 1887 left his music publisher and amateur composer father and his stepmother (whom he found unbearable) to live in Montmartre (link to map), the north Parisian neighborhood famed as an artistic haven. Much to Satie’s dismay, he did not achieve the success that he had hoped for in Montmartre, despite a brief stint as composer for the “Ordre de la Rose-Croix catholique du Temple et du Graal” (Catholic order of the Rose-Cross and of the Temple and the Grail), a secret society that, in a certain respect for Satie harkened back to medieval music and Gregorian chant – in his youth, he had studied under a church organist who impressed upon him a fascination for chant; this informed much of his music. Thus in 1898, he once again packed up his things and moved, this time to Arcueil (link to map), a suburb just south of Paris. It is here where he lived the remainder of his life. In the period 1898-1905, Satie made a living by frequenting café-concerts and cabarets, both as performer and composer; between 1899 and 1909, he wrote 19 cabaret songs (one example is 1904’s La Diva de l’Empire), and many of his other works from this period are inspired by a combination of cabaret or music hall style and impressionism (one could say Debussy had had an impression on him; they became long-time friends). In 1905, Satie, wanting to improve his compositional skills, enrolled himself in Vincent d’Indy’s Schola Cantorum. He finally achieved wide recognition in 1911 when Ravel performed some of his solo piano works. The next big step came in 1917 when, with the help of Jean Cocteau, Satie collaborated with Sergei Diaghilev, Léonide Massine, and Pablo Picasso to create the scandalous ballet Parade; many ballet-goers did not appreciate Picasso’s costume design or Satie’s biting sense of humor.

Two of Picasso’s costumes for “Parade”

And it is just that that ties Satie’s oeuvre together – although there are a number of radically different influences on his music from different periods of his life that range from Gregorian chant to Debussyan impressionism to cabaret songs, Satie’s scathing sense of humor and his biting irony are nigh omnipresent.

1924 – Satie’s penultimate year – was nonetheless a rather significant year for performances. In January of that year, the Ballets Russes premiered Gounod’s opéra comique Le Médecin malgré lui in Monte Carlo with Satie’s recitatives, requested of him by Diaghilev. Working again with Picasso and Massine, he premiered the ballet Mercure in June of that year; the work was commissioned by the Comte Etienne de Beaumont, an aspiring impresario. Just like 1917’s Parade, Mercure provoked scandal at its premiere. And, continuing with the tradition, Relâche, a ballet made with the participation of Francis Picabia and Jean Börlin, also instigated outrage at its premiere in December of 1924. Relâche was also accompanied by a film, Entr’acte, for which Satie composed the first ever synchronized film score. One factor that made these ballets so difficult to digest – particular at the time – was the modernity and, in a sense, the vulgarity of their music. Satie’s writing often focuses heavily on repetition, and whereas more traditional classical or romantic music seems to have a trajectory – a sense of motion from beginning to end – Satie’s music relies rather on a sort of stasis, where there is no clear movement, neither progression nor regression. Put simply, his music does not do anything; instead, it is. Throw into the mix rather avant-garde designs and costumes courtesy of the “Pica’s” (Picasso and Picabia), the often rather bourgeois sentiment of those attending the ballet, salt to taste – and voilà! We have a fiasco.

Finally, there is one more point that I would like to draw attention to, and that is Satie’s connection to the artistic culture of 1924 Paris. As previously mentioned, his influences were fairly eclectic; in addition, they were comparatively very few. The only major composer to have a lasting impact on his work was Debussy. Although strains of Ravel or Fauré can be found in sections of some of his earlier writing, their influence on Satie was short-lived. Instead, Satie was largely influenced by music not traditionally part of the “canon” of art music – at least not in Satie’s lifetime. His emphasis on popular music and cabaret songs often led to a disconnect with the world of “high art,” as he simultaneously rejected this world through his satire and parodies. In a sense, Satie was the “original” P.D.Q. Bach (the brainchild of Peter Schickele, of J.S. Bach’s 20 children, hilariously, the 21st). Indeed, much of Satie’s legacy comes from his parody works, such as Véritables préludes flasques and Embryons desséchés. His sense of humor reflects the Dadaist spirit and the disillusionment felt by many (particularly artists, musicians, and writers) after the Great War. In these two senses – eclectic influences from outside the traditional canon of Baroque, Classical, and Romantic art music and keen irony – Satie very much connected with the Paris of 1924 and the artistic community there.