Bonjour Monsieur Emile,

I was inclined to write to you after your publication in The League of Composers review. I am aware that you may not have enjoyed Les Biches, but after reading it, I was deeply disappointed in your review of Poulenc. To accuse Francis Poulenc of attempting to break free of his old style by embracing pettiness and frivolity is absolutely uncalled for. Though I may be biased, I believe that he has always been able to employ different musical styles and visions within his compositions. This ability has allowed him to write pieces that embody his views on sexuality, intimacy, desire and social standing, yet also craft pieces that specifically cater to popular styles among the french people. I would like to pose to you the possibility that you are incorrect in your assessment. Ultimately, Les Biches is not an attempt by Poulenc to reject a Debussyian style, but is a commentary of the sexual insurgency of Paris.

Shortly after the premiere of Les Biches, you claimed that it was “a vain effort to change [Poulenc’s] ‘Debussyian’ style by utilizing caricature and triviality.”1 It is true that Francis had a particular style at the beginning of his career. Rapsodie nègre, which premiered in 1917 and was dedicated to Erik Satie, had a distinctive agenda and musical ideas.2 As a young composer, Francis was dedicated to creating a French Nationalistic sound.3 Satie provided him a template from which to construct such a categorically french piece. The Rapsodie was inspired by the jazz influences in Satie’s Parade, as well as the black phenomenon that was sweeping the nation. It was not the first piece Francis composed, but it was his first performed piece. I thoroughly enjoyed composers like Milhaud’s reaction to black culture and Jazz, incorporating blues harmonies and syncopated rhythms into an otherwise classical-type work. This exact borrowing technique is utilized in Rhapsodie; an opening syncopated rhythm is written in whole-tone harmonies. The whole tones themselves, and other effects, are a nod to another great French composer, Claude Debussy. Throughout the piece, Poulenc employs planing, a method where the melody is a chain of unrelated harmonies and chords in the same inversion moving step-wise; one of Debussy’s most recognizable musical traits. Of course Francis has composed pieces that were a nod to Debussy, but Les Biches is simply achieving a different goal.

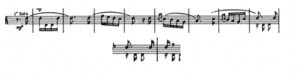

I, myself, was not quite charmed to see that Francis was simply following in the footsteps of others.4 But Poulenc had the ability to illustrate what he wanted to convey, and construct an entirely new perspective. Six years after the premiere of Rhapsodie nègre, he premiered a work that had everything to do with the sexual revolution happening in Paris. Poupoule and I were very aware of each other’s sexuality and we were both with different men at the time.5 Les Biches was a ballet that, in my opinion, was a brilliant reaction to the freedom that most of the gay persons in France were experiencing. It was adored, accepted, and ultimately performed very often throughout the next couple years. I even recently read an article in the Paris “L’Humanité” about a performance of the ballet that encouraged readers to go because of its excellent composition.6 The composition, itself, directly highlights Poulenc’s sexuality and sexual expression. Within the adagio section of the overture and throughout the rest of the ballet, there is a love theme crafted to accompany the main characters (ex. 1A).

Example 1A; Poulenc Les Biches Adagietto (m1-11)

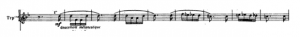

It first is repeated in the trumpets, but not all together identical. The end of the phrase modulates away, to develop into something else (ex. 1B).

Example 1B; Poulenc, Les Biches, Adagietto (m28-36)

This disfiguring of the supposed love theme happens throughout the movement. Because of this constant modulation and distortion, the theme, itself, evokes the feeling that this love is too good to be true and isn’t quite what it seems. This, combined with the androgyny, cross-dressing, and homo-erotic undertones that are prevalent throughout the ballet, expresses the kind of sexual freedom that Poulenc, himself, was feeling.7 The important thing to note about my old friend Francis, is that this piece was not anti-Debussy, but a queer reading of French society.

Les Biches is not an attempt to divert his avant-garde style, but a successful voyage into a different perspective. This so-called frivolity is simply a blithe emotion that Francis worked to incorporate to each of his pieces. He once said to me that “[French] composers write profound music, and when they do it is leavened with that lightness of spirit without which life with be unendurable.”8 Frivolity is important in life and therefore in music. Poulenc is a many faceted man who does not need to be confined into one style and one mindset. I have always praised the work my dear friend has crafted and will continue to do so until he stops composing at this level.

I hope you will take some time to consider my opinion. Poulenc is a wonderful composer and one who I’m sure will become one of the greats. My best regards to you and your current endeavors.

Votre fidèle

Cocteau

1 Vuillermoz, Emile. “The Legend of The Six.” The League of Composers Review 1.3 (1924): 15-19. Web.

2 Schmidt, Carl B (1995). The Music of Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) – A Catalogue. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

3 Roland, Gelat, “A Vote for Francis Poulenc,” Saturday Review of Literature, Janurary 28,1950. 57. From Fisk, Josiah, and Jeff Nichols. Composers on Music: Eight Centuries of Writings. Boston: Northeastern UP, 1997. Print.

4 Poulenc, Francis, and Myriam Chimènes. Correspondance, 1910-1963. Paris: Fayard, 1994. Print.

5 Predota, Georg. “Parisian Sexuality; Francis Poulenc and Friends.”Interlude. N.p., 6 Nov. 2013. Web. 3 Oct. 2015. (http://www.interlude.hk/front/parisian-sexuality-francis-poulenc-and-friends/)

6 Jaurès, Jean. L’Humanité [Paris, France] 17 May 1926: 6. Newspaper Archive. Web. 10 Oct. 2015

You must be logged in to post a comment.