This project is a companion to the appendix of Carol J. Oja’s Making Music Modern, in which Oja compiles a list of programs of the following new-music organizations:

- Pro Musica Society

- American Music Guild

- International Composers’ Guild

- League of Composers

- Copland-Sessions Concerts

- Pan American Association

In this project, I visually compile Oja’s data, incorporating them with their geographic information to create a unique resource. While these maps simply reproduce Oja’s data, these visual representations allow for a more holistic and accessible reading1.

Seeing An Argument

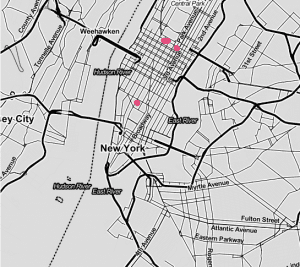

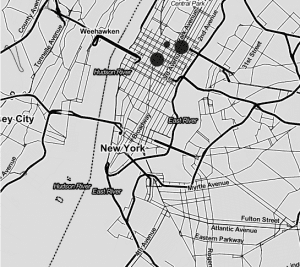

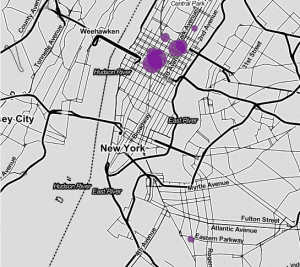

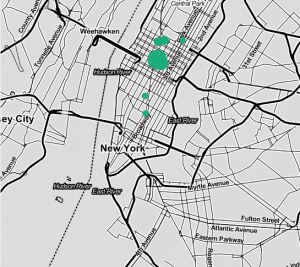

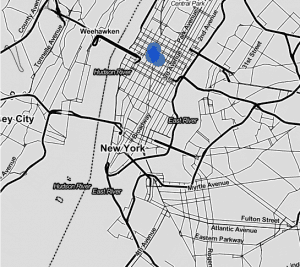

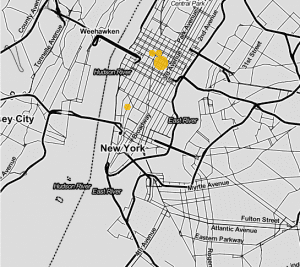

To begin, I will first present a derivation of the original map, which aggregates program information into concerts, and then displays the information visually, with number of concerts performed being represented on a scale of size. The following static maps are visual representations of the number of concerts performed by specific composer organizations:

From these 6 maps, it can be seen rather clearly that all 6 composer organizations had some hold in central Manhattan, and the majority of concerts took place in this area. Few composer organizations stray outside of downtown Manhattan, and if they do, it’s certainly not to a significant degree. These maps affirm an already well-established thought—that the majority of modern music in New York took place in downtown Manhattan, but what makes this field (that is, geography) unique, is that it establishes this fact within a matter of seconds. For more exploration on concerts in New York, take a look at the source of these maps.

But now let’s take a step deeper into Oja’s data, exploring how we can find and develop research questions about modern music societies of 1920s New York:

The Deep Map

How to Use This Map

This map is the parent map of Concerts of Modern-Music Organizations, and compiles every work documented through programs of modern music societies. With this broadening of information comes an almost overwhelming uncertainty of what to do next. My personal advice would be to start with the widgets at the bottom/side of the map. Though the use of widgets, you can narrow down the visual representation of data. I encourage you to play around with different buckets, examining how they relate and interact. Ask questions such as, “How do venues relate between the International Composers’ Guild and the League of Composers?” This question allows us to see that these composer organizations intersect at certain venues, but other venues, like Anderson Galleries, are exclusive to one composer organization. This map is useful in generating research questions with a specific geographical lens, questions that would not arise through the appendix itself.

What Kind of Map Is This?

In answering this question, I highlight a key question within the digital humanities and GIS. Maps can have several functions. Among many roles, digital mapping can compile big data in a short amount of time2, present spatial arguments3, criticize research methods, or serve as a recombinant source4. In some way or another, my map is accessible vis-à-vis all of these roles, yet its primary focus is to serve as a “thick map.”

Given its multiple layers and its high quantity of data, this map brings to mind Todd Presner, David Shephard, and Yoh Kawano’s Hypercities: Thick Mapping in the Digital Age. The three define thick mapping as “the process of collecting, aggregating, and visualizing ever more layers of geographic or place specific data5“. In this way, the collection of Oja’s data, as well as the aggregation of her categorizations into specific layers on the map contribute to its effectiveness as a “thick map.” If this map were to be represented physically (as opposed to digitally), there would be no diversity in how the data is represented, and the map would be too overwhelming to analyze. Through the various layers, we are able to diversify visualizations of the data to allow for a multitude of different interpretations. Simply, you can never look at the map the same way twice.

In this way, this map has many stories to tell, which is itself both a positive and negative thing. While it is easy to find a unique argument through the map, it is difficult to express this argument through the map alone. In other words, this map does not stand alone in presenting arguments about modern-music societies of New York, but it can serve as a supplement to verbal arguments derived from a specific interpretations. In other words, if you expect a recreation of your argument, you must simultaneously verbally explicate your argument as well as how your arrived at that argument.

Research Problems and Moving Forward

Oja’s research is, admittedly, as accurate as it can be. The challenge of this project lies in verifying absolute accuracy within each program concerning premieres. Primary sources are not always reliable and therefore the following resource cannot claim to be an absolutely accurate representation of premieres of these modern music societies. They can, however, be a useful resource in seeing what these organizations viewed as premieres and should be regarded as such.

Moving forward, this map poses great potential for future research in music organizations in the 1920s. Where Oja did strenuous, awe-inspiring work, the sheer scale of it is daunting to the novice researcher. This map allows for that work to be communicated in to the public in a comprehensive, holistic, and exciting way. I hope that it inspires the user to continue to explore, asking questions all along the way.

Notes

1 Carol J. Oja cites the following sources in her compilation of the programs:

- “American Music Guild: Programs,” uncatalogued program file at NN.

- “International Composes’ Guild: Programs,” uncatalogued program file at NN.

- “League of Composers: Programs,” uncatalogued program files at NN and DLC.

- The League of Composers: A Record of Performances and a Survey of General Activities from 1923 to 1935. New York: The League of Composers [1935].

- Lott, R. Allen. “New Music for New Ears’: The International Composers’ Guild.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 36/2 (1983): 266-86.

- Metzer, David. “The League of Composers: The Initial Years.” American Music 15/1 (Spring 1997): 59-66.

- Oja, Carol J. “The Copland-Sessions Concerts and their Reception in the Contemporary Press.” The Musical Quarterly 65/2 (April 1979): 227-29.

- “Pan American Association Programs,” DLC.

- “Pro Musica: Programs,” Schmitz-CtY.

- Root, Deane L. “The Pan American Association of Composers (1928-1934).” Yearbook for Inter-American Musical Research 8 (1972): 62-66.

- Wiecki, Ronald V. A Chronicle of Pro Musica in the United States (1920-1944): With a Biographical Sketch of its Founder, E. Robert Schmitz. Ph. D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin, 1992. 3:654-62.

2 Philip Ethington and Nobuko Toyosawa, “Inscribing the Past: Depth as Narrative in Historical Spacetime” in Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives, ed. David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan, and Trevor M. Harris (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015), 72-101.

3 Diana Sinton, “Critical Spatial Thinking,” The International Encyclopedia of Geography, ed. Douglas Richardson, Noel Castree, Michael F. Goodchild, Audrey Kobayashi, Weidong Liu, and Richard A. Marston (Hoboken: Wiley & Sons, 2017), 2-9.

You must be logged in to post a comment.