Elsa Collaer

19 Rue du Mont Aigoual

Paris, Île-de-France, France

My Dearest Elsa,

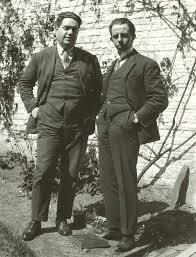

I hope you are doing well and having a nice stay with your cousin. I recently visited our good friend Darius Milhaud. His place was a bit messy but that is reasonable for such a creative musician. I had a great talk with him about his recent work La Création du monde, a ballet featuring jazz elements.

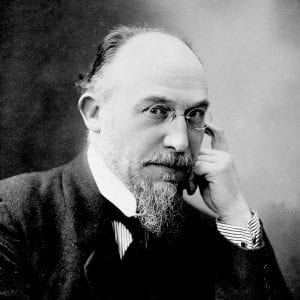

Darius has always been a lover of melodies and is a great admirer of a variety of musicians especially Satie. He believed that Satie’s music was of infinite beauty because of its genuine melody, simple expressiveness, and clear, luminous form.

It is through his discovery of others’ music that “ we find Milhaud reacting with joy to everything human and with indifference and even hostility to what he considers narrow individualism”.[1] This leads to my idea that he believes that the only way to find beauty in music is to find its foundation. The way he discussed music made me realize that his idea of foundation stems from traditional aspects which he utilizes not only in La Creation du monde but also in his other pieces.

I asked for him to give an example of this “foundation” he was referring because it seems he is a strong believer of traditionalism. He then proceeded to give a story about the marvelous treasures he found in the United States. He said while in New York, he spent several evenings in Harlem. It was there that he uncovered the wonderful beauty of jazz yet it was not his first experience. Milhaud said that “this authentic music had its roots in the darkest corners of the Negro soul…”.[2]

He further explained that the rhythm from their heritage was found deep anchored in the souls. That prompted me to ask if all American music were like this. He chuckled and laughed and said something along the lines of Black jazz being “far removed” from the current sophisticated American style of dance music.[3] It reminded me of a statement he wrote in a previous letter to me about the primitiveness of African music. I remember him mentioning in a letter from Harlem that when he listened to the music, he could feel “the intensity and repetitiousness of the rhythms and melodies….arouse deep emotions in its listeners”, just like him.[4] He was so intrigued by this concept of jazz displayed by “the evolution of jazz band and Negro music in North America” that he wanted to celebrate these unique qualities in some of his works.[5]

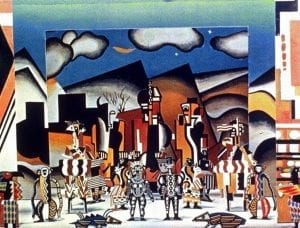

I believe that was his inspiration for his recent work La Création du monde. It was a fine example of this foundation of tradition. He utilized the jazz elements that he had the pleasure of listening to while in Harlem and placed them as the roots of the work. The piece does contain new ideals of French music but yet still keeps this idea of tradition in the foreground. If you look closely at the work like I have you will notice a feeling of gentle agitation, a sort of springtime ebullience underlies the entire work. There is also a syncopated style directly inspired by African rhythms, which transports this style of jazz to an entirely different level of expressiveness.[6] Elements of ragtime and the blues become solemn and imposing in this piece. There is even an entire range of emotion from peacefulness to passion as if humans do not have a response to nature’s mysteries.

Yet, Milhaud still finds a way to implement French ideas into his music. Mixing the ideals of the new and the old. He said that “For Africans, nature is a luxurious nurturing forest, not a desert”.[7] So when looking at the instrumental lines, you discover that they are more flowy than African jazz. In addition the combination of piano and percussion gives a kind of brassy menacing timbre to bass lines. The aspect of the fugue also comes into play when it appears after the overture and is referenced in different parts of the piece. I believe the fugue concept is included to demonstrate his mastery of the French tradition. Each part has importance in this wonderful story of creation. He attempts to recreate the jazz ensemble into different instrumental contexts.[8] From the burst of sound to the ranging emotions to the story it portrays, Milhaud does not cease to surprise me. He mentioned that ever since he came back from Harlem he was “resolved to use jazz for a chamber work”.[9] And he did just that. He wanted this piece to represent the African tradition and not be the typical jazz music every day French people were used to hearing. He wanted to bring something new, something fresh, the real roots of jazz. I asked him why he used this style of music? and he responded that it had various “experimental potentialities” that he believed was not fully utilized in dance music.[10]

It made me recollect our previous meeting when he said “I am a Frenchman from Provence, and, by religion, a Jew”.[11]

This statement demonstrated pride not only in his religious beliefs but in his national French citizenship and the influence it brought him. At the time he was in the process of his Six chants populaires hébrïaques (Six Popular Hebrew Songs – 1925) (Insert hyperlink). I strongly believe that he utilized his Jewish background as his theme for this piece. His strong Jewish faith pushed him to derive features from Polish or Ukranian Jewry. I remember reading his interview with Claude Rostand in the paper. One phrase that stuck with me was “ If one goes back to ancient popular themes, it is indeed to bring them back to life, to give them new strength, to actualize them…”.[12] He was trying to express his Jewish roots through this as well as exploring his French-Jewish identity by implementing old elements with the new. His home in Aix de Provence was not only a source of his musical inspiration but a huge part of his cultural identity.[13] It made me recognize that this idea is not only found in La Création du monde but in his other works like his Le bœuf sur le toit (The Ox on the Roof: The Nothing-Doing Bar – 1920).

He was so fascinated by the Brazilian Popular songs that he decided to use them into this work. It’s absolutely brilliant! It’s becoming clear to me that he incorporates traditional elements to tell a story in his pieces. Whether these aspects are primary or underlying sources is up to him. When he implements them I believe it is a way of him exploring and reflecting on these experiences through music. It is as if each feature is a snapshot of the surroundings he once immersed himself in, a snapshot that he wants to illustrate to his audiences but with a new flavor of perspective. One main point he always emphasizes is these outside influences to French music “enriches the tradition”, directly relating back to the importance of traditional elements as the basis with a mixture of French classical qualities.[14]

Elsa, I cannot wait to take you to see this wonderful work! Milhaud gave me the opportunity to sit in and view this work in the making. Blaise Cendrars created the theme for this work from African folklore and it’s incredible. Just like the music, the staging and costumes display elements of the Jazz tradition that Milhaud is trying to portray. It stressed the theme of ardor and harmony without any trace of violence or fear. I feel Milhaud “has brilliantly transposed jazz and raised it to a superior plane”.[15]

Anyways I will not spoil the rest of it since I will be taking you to see it when it premieres on October 25.

I am excited to see how it develops until then. Milhaud is such an exquisite man with character and life and I hope to dine with him again soon. He does make some great conversation. Hope to see you soon my sweetest!

With love

Paul Collaer

[1] Collaer, Paul, Darius Milhaud, (San Francisco Press Inc. 1988), 17

[2] Milhaud, Darius. Notes without Music, (Alfred A. Knopf Inc. 1953), 136.

[3] Collaer, Paul, Darius Milhaud, (San Francisco Press Inc. 1988), 69

[4] Collaer, Paul, Darius Milhaud, (San Francisco Press Inc. 1988), 76

[5] Collaer, Paul, Darius Milhaud, (San Francisco Press Inc. 1988), 78

[6] Collaer, Paul, Darius Milhaud, (San Francisco Press Inc. 1988), 70

[7] Collaer, Paul, Darius Milhaud, (San Francisco Press Inc. 1988), 71

[8] Kelly, Barbara L. Traditions and Style in the Works of Darius Milhaud. (Ashgate Publishing Company 2003). 171.

[9] Milhaud, Darius. Notes without Music. (Alfred A. Knopf, Inc 1952). 137.

[10] Gendron, “Negrophilia,” in Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club: Popular Music and the Avant-Garde (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 89.

[11] Milhaud, Darius. Notes without Music. (Alfred A. Knopf, Inc 1952). 25.

[12] Darius Milhaud: Enregistrements historiques, 1929-1948. Archives de la Phonothèque Nationale, 49

[13] Kelly, Barbara L. Traditions and Style in the Works of Darius Milhaud. (Ashgate Publishing Company 2003). 33.

[14] Kelly, Barbara L. Traditions and Style in the Works of Darius Milhaud. (Ashgate Publishing Company 2003). 30.

[15] Gendron, “Negrophilia,” in Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club: Popular Music and the Avant-Garde (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 115.

You must be logged in to post a comment.