Friday, May 9, 1924

The Opèra.

Wikimedia Commons.

Paris was filled with musical performances to attend last night: operas, recitals, revues, and countless theater spectacles. The Opera Comique displayed Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro at eight, and at eight-thirty, Bizet’s l’Arlesienne in the Odéon. Pianists Grégoire Gourévitch and Marius-François Gaillard gave recitals with works from Debussy and Milhaud. Older classics like Mozart and Schubert rang out from the Salle des Agriculteurs, and today’s popular songs lit up revues all around the city.1 Despite all of the glittering spectacles one could attend, conducting master Serge Koussevtizky‘s orchestral concert at the Opéra stood out as last night’s only performance to feature true innovation in modern French music with Arthur Honegger’s new symphonic movement, Pacific 231. This intriguing modernist work borrows from the old traditions in surprising ways, never going to extremes to be avant-garde; yet is a fully innovative work and a huge success with the Paris audience. Honegger’s simple creativity is the new standard that French music should hold to instead of viciously rejecting musical German-ness. That being said, the prestigious Paris Opéra was clearly the place to hear live music last night. Its intricately-adorned concert hall3 was packed with Parisians who were in a frenzy to hear Honegger’s strange new train-music.3 The audience adored the piece and applauded for nearly seven minutes without pause!4 It’s already so popular that Koussevitzky will repeat it in his concert repertoire next week.5 The French public is clearly eager to receive Honegger’s new direction in concert music.

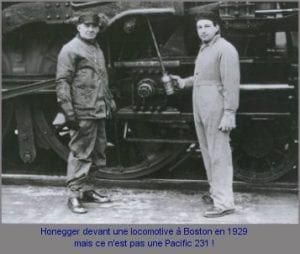

Arthur Honegger with a Train.

arthur-honegger.com.

Although Pacific 231 was generally adored, not everyone understood its creativity. One critic of last night’s performance commented that the piece is merely a “collage of train noises.”6 Yes, the piece is primarily the music of a machine.7 However, Honegger’s intention was more complex in writing this piece. He reported that he wanted to translate the visual experience of a speeding train, as well as its sounds, into the orchestral texture.8 Honegger finds a new art form in the machine, saying that “locomotives vibrate with harmonies, they sing.”9 This machine-art may be an expression of what some call “lifestyle modernism.”10 As many French composers create music expressing the frivolities of aristocratic life, Honegger expresses another kind of triviality, in a lifeless machine. This is exactly the kind of subject that Parisians appreciate in music, since they don’t want to hear anything too deep or meaningful.11

One could loosely compare the piece to a Romantic-era programmatic work– in Pacific 231, you hear steam hiss, wheels screeching, rattling, and a whistle clearly depicted in the music.12 Honegger shows no intention of avoiding this parallel to the past. Another comparison is that his interest in the art of the machine could be paralleled with German serialism– yet Honegger’s train moves with an essence of vibrant colors and joy rather than mathematical structure.13 His music is simple, effortless, and clear. It’s a perfect model for the modern French ideal, despite the nods to such anti-French music as German Romanticism.

Honegger’s music itself employs many traditional, even old-fashioned methods of composition, while maintaining a fully-modern sound and concept. The orchestral movement begins in a slow tempo that gradually picks up speed. Strings and woodwinds blend easily with the low brass. Percussion instruments rarely rise above the orchestral texture, yet add color and excitement.14 Honegger’s clever instrumentation creates a world of sounds that may seem unusual coming from a symphony orchestra, yet only the traditional orchestral instruments are used.15 There are no extreme modernist tendencies in using bizarre instruments or techniques to achieve the required sounds, as many modern composers do– and this makes his music much more accessible to performers and audiences alike.

Honegger also returns to rather ancient ideas in musical form. As the piece progresses, it seems to resemble a variations set. Distinct sections of music pass by the listener, with the later variations incorporating melodic and motivic material from the previous. For example, a triplet figuration in the woodwinds returns multiple times, later layered with a soaring brass line and frantic strings.16 This formal structure brings a listener back to J. S. Bach’s variations and contrapuntal style; Honegger himself has mentioned his intention to create music stylistically similar to a chorale by Bach.17 His toying with the traditions of the baroque is nothing new–other contemporary French composers’ work have elements of Neo-Classical or Neo-Baroque style as well. Yet, in Honegger’s piece, the neo-baroque influences are hardly exaggerated and never overwhelm–they simply become part of the structure of his musical train, each variation a single car that passes by the listener. Honegger neither asserts extreme modernity nor extreme devotion to the traditions of the past. They simply become one in his music, and are fresh for his adoring French audiences.

While Pacific 231 was the standout work of Koussevitzky’s concert, the other works were performed nearly perfectly in this all-around top concert. Like Honegger’s piece, the concert as a whole was a mix of the old and the new, and represented composers of many nationalities. Prokofiev himself was present at the concert, and performed his own Piano Concerto no. 2.18 Last night’s concert was the first performance of the Concerto after Prokofiev reconstructed the damaged work from a devastating fire several years ago.19 The oldest piece on the program, by Italian baroque composer Pietro Antonio Locatelli, was the solemn Sinfonia Funebre. Ravel’s orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, Manuel de Falla’s El Amor Brujo, and Alexandre Tansman’s Légende were the more recent compositions on the program.20

Just as last night’s concert combined the contemporary with the classics, Honegger’s Pacific 231 is a perfect blend of old and new musical elements. French music is all about simplicity, clarity, elegance; Honegger creates just this kind of music in a piece about a train. He avoids the extreme, utter rejection of traditional musical influences. Doing this proves his creativity with Pacific 231, and the audience loved it as well. A work of music doesn’t require a scandal in order to prove its innovation.

1 Maxime Girard, “Courrier des Théatres,” Le Figaro (Paris 1854), (May 8, 1924): 5, BnF Gallica, Accessed November 11, 2015.

2 Anthony Gishford, Grand Opera: the Story of the World’s Leading Opera Houses and Personalities (New York: Viking Press, 1972), 61.

3 Olin Downes, “Music: New York Symphony Opens Season,” New York Times (1923-Current File), November 1, 1924, ProQuest, accessed November 13, 2015.

4 “Setting Locomotives to Music,” Literary Digest 83, (October 25, 1924): 29, Readers’ Guide Retrospective: 1890-1982 (H.W. Wilson), EBSCOhost , accessed November 13, 2015.

5 Jane F. Fulcher, Composer as Intellectual: Music and Ideology in France 1914-1940 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 187.

6 Roger Nichols, The Harlequin Years: Music in Paris 1917-1929 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 233.

7 “Setting Locomotives to Music,” 29.

8 Downes.

9 Arthur Honegger, quoted in Nichols, 234.

10 Nichols, 234.

11 Nichols, 236.

12 Arthur Honegger, “HONEGGER – PACIFIC 231 (MOVTO SINFÓNICO NO 1) – BERNSTEIN /NVA YORK,” Youtube, published December 17, 2014.

13 Marcel Delannoy, quoted in Nichols, 234. “…themes of confidence an joy such as Honegger employed in 1924!”

14 Honegger.

15 “Setting Locomotives to Music,” 29.

16 Honegger.

17 Arthur Honegger, quoted in Nichols, 233. “From the musical point of view I composed a kind of large chorale variation, shot through the first part with alla breve counterpoint and conjuring up the style of Johann Sebastian Bach.”

18 Girard, 5.

19 Michael Steinberg, “Prokofiev: Concerto No. 2 in G Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 16,” San Francisco Symphony, accessed November 11, 2015.

20 Girard, 5.

Bibliography

Downes, Olin. “Music: New York Symphony Opens Season.” New York Times (1923-Current File), November 1, 1924. ProQuest, Accessed November 13, 2015.

Fulcher, Jane F. Composer as Intellectual: Music and Ideology in France 1914-1940. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Girard, Maxime. “Courrier des Théatres.” Le Figaro (Paris 1854), (May 8, 1924): 5. BnF Gallica, Accessed November 11, 2015.

Gishford, Anthony. Grand Opera: the Story of the World’s Leading Opera Houses and Personalities. New York: Viking Press, 1972.

Honegger, Arthur. “HONEGGER – PACIFIC 231 (MOVTO SINFÓNICO NO 1) – BERNSTEIN /NVA YORK.” Youtube. Published December 17, 2014.

Nichols, Roger. The Harlequin Years: Music in Paris 1917-1929. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

“Setting Locomotives to Music.” Literary Digest 83, (October 25, 1924): 29-30. Readers’ Guide Retrospective: 1890-1982 (H.W. Wilson). EBSCOhost , Accessed November 13, 2015.

Steinberg, Michael. “Prokofiev: Concerto No. 2 in G Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 16.” San Francisco Symphony. Accessed November 11, 2015.

You must be logged in to post a comment.